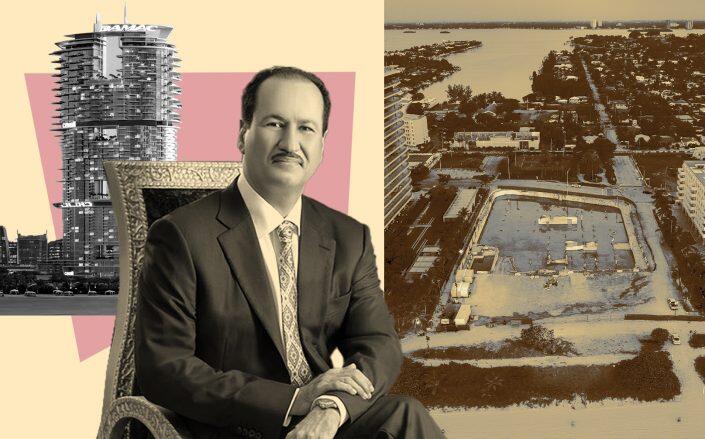

From left: Cavalli Tower with Hussain Sajwani of Damac and the Surfside condo collapse site (Damac, Wikimedia, Getty)

Now streaming: TRD’s podcast “Deconstruct” on Damac Properties and what’s next for the Surfside collapse site.

Hussain Sajwani has made a career out of going against the tide.

While his compatriots scaled back after the 2008 market downturn, Sajwani, the founder of Dubai-based Damac Properties, announced his biggest project yet, the 42 million-square-foot Damac Hills. And years later, as many high-profile businesses severed ties with the Trump Organization over Donald Trump’s anti-Muslim rhetoric on the campaign trail, Sajwani did not budge. He opened the Middle East’s first Trump-branded golf course at Damac Hills in 2017, with Eric Trump and Donald Trump Jr. as guests of honor.

His moves have baffled other developers. “Mad,” is what they thought of him, he recalled in a 2016 interview with Forbes, because in the early 2000s he sold prime parcels in the heart of the city in order to buy land in the then-barren Marina neighborhood. Two of his 80-plus story towers are among the canyon of skyscrapers that today define the Marina skyline.

The flamboyant billionaire now has his sights set on the U.S., and not just any site: Damac has emerged as the stalking horse bidder on one of the country’s most emotionally charged parcels, one that many local developers have refused to touch: the Surfside site in South Florida, where nearly 100 people died in June when the condo tower on the property collapsed.

“If they were just building in New York City, it would just be another building. If they come to Surfside, I think we have someone who has truly entered the marketplace in a big way.”

In September, Damac offered to pay $120 million for the nearly 2 acres of oceanfront land where Champlain Towers South previously stood. The choice is controversial – some find the idea of developing anew where their loved ones died unthinkable – but allows a newcomer a chance to enter a hot luxury market.

“If they were just building in New York City, it would just be another building. If they come to Surfside and say, ‘We want to redevelop the Champlain site,’ we have someone who has truly entered the marketplace in a big way,” said Keith Poliakoff, a South Florida-based real estate attorney. “The Surfside location provides a unique opportunity for a worldwide developer to make a name for themselves in the U.S.”

Damac has developed 35,000 residential units, mostly in Dubai but also in Jordan, Lebanon, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and London. The company, which has a market cap of over $2 billion, is publicly traded on the Dubai Financial Market, after having been the first Middle Eastern developer to list on the London Stock Exchange in 2013.

Miami is a “natural fit, given its reputation for being a popular, luxurious destination,” said Niall McLoughlin, a spokesperson for Damac, confirming that the developer intends to build a high-end residential project at the Surfside site. “We fully understand the emotions surrounding the site and wish to approach the development with full consideration of the community’s benefit.”

Hussein and the city of gold

Damac is a mystery to most Americans. But in the Middle East, it has a long, checkered history.

Sajwani’s moniker, the “Donald Trump of Dubai,” is not just a reference to his prized ties to the Trump Organization, dealings that include BelAir at The Trump Estates villas in Dubai. It’s also a nod to the Emirati’s penchant for flashy, headline-stealing projects – and his skills as a hype man.

Buy a Damac home, and Sajwani may throw in a Lamborghini. Buy a villa, and you might get a studio apartment as a bonus. On more than one occasion, buyers were entered into a raffle to win a six-seater private jet.

Sajwani, now in his late 60s, grew up in Dubai as the eldest of five children in a middle-class family. His father sold goods at a souk and his mother door-to-door to local women.

“I used to listen to all the stories, the successes and the failures, the issues that an entrepreneur faces in life,” he told the Financial Times of his childhood.

We fully understand the emotions surrounding the site.

He was part of the first wave of Emirati students that the UAE sent on government scholarships to the U.S. While studying industrial engineering at the University of Washington in Seattle, he had a side gig selling timeshares in the UAE Upon returning home, he worked for state-owned Abu Dhabi Gas Industries (now ADNOC) and then struck out on his own, using funds from his timeshare business to start a catering company with clients including the U.S. military in Iraq, Afghanistan and Bosnia.

In the 1990s, Sajwani invested in dotcom firms such as Juno and mail.com, and built small hotels in Dubai. He founded Damac in 2002, around the time the UAE’s rulers opened its property market to international investors – formerly, only UAE citizens and those of the neighboring Gulf countries could buy property there.

Oil prices had fallen and the government pursued rapid economic diversification, according to Faisal Durrani, head of Middle East research at Knight Frank. This quickened Dubai’s evolution into a lux real estate hub, Durrani added.

Cavalli Tower (Damac)

Damac’s marquee Dubai projects include Aykon City, which the developer describes as a city-within-a-city with four residential towers and an entertainment and retail plaza; Damac Towers by Paramount Hotels & Resorts, which has 1,200 residential units and a hotel; and the the 63-story Paramount Tower Hotel & Residences Dubai. In 2019, Sajwani’s private investment firm bought the luxury fashion brand Cavalli, and Damac is now at work on a 70-story Cavalli Tower, which Sajwani described as an “an effortless extension of (Cavalli’s) vision beyond patterns, garments and sensational catwalks.”

But all that glitz hasn’t come without serious setbacks. After the 2008 downturn, Damac laid off hundreds of employees, renegotiated with contractors and paused construction on several projects. It moved buyers from canceled towers to buildings that were well on their way, prompting a barrage of lawsuits, according to a 2013 article in the Financial Times.

“There was a fire and everyone wanted to leave the room,” Sajwani told the publication.

Sajwani took his biggest hit not in his hometown, but in Egypt, where he was sentenced to five years in prison in absentia over a land deal with the Hosni Mubarak regime that allegedly bilked the Egyptian people of $41 million. He did not serve time, thanks to a Damac follow-up suit against Egypt through an investor-state dispute settlement tribunal. (A 2016 BuzzFeed investigation of the ISDS arbitration system, created under a series of trade treaties, chronicled how it acts as a tool for companies and executives to escape punishment, while countries fear its rulings to an extent that they willingly upend their own laws.)

Attorneys for Damac said the conviction was politically motivated. King & Spalding’s Ken Fleuriet called it “guilt by association,” adding that doing business with the Mubarak government does not equate to wrongdoing, according to BuzzFeed.

Sajwani’s sentence was canceled and Damac dropped its suit in a 2013 settlement.

Damac has also faced civil suits from buyers. In one case, it was ordered to pay $710,000 to a Canadian buyer over allegations of construction delays, according to a 2016 Forbes report. Another dispute with a German buyer was settled confidentially.

McLoughlin waved off the suits, saying “occasional litigation is common in the real estate industry.”

The Egypt case is “very old news,” he added.

Fast friends

In a world where money trumps politics, the Sajwani and Trump families are close beyond their business deals.

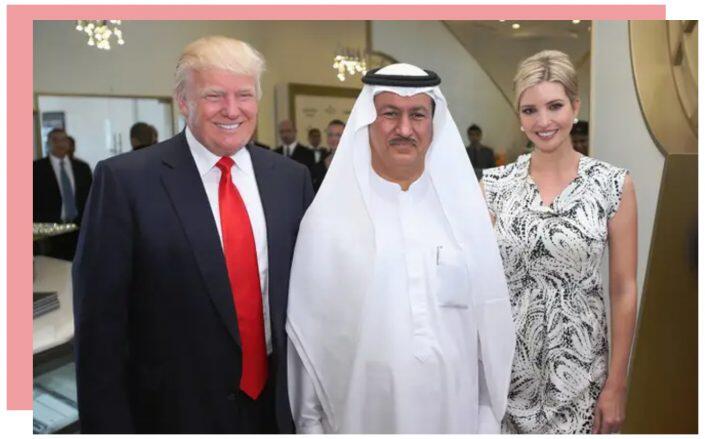

Donald Trump, Hussain Sajwani and Ivanka Trump (Damac)

“My wife and Ivanka are very good friends,” Sajwani said in a 2017 NBC interview. “They send emails. She’s been here, to my house. We’ve been in New York having lunch and dinners with them regularly. You enjoy working with somebody — it’s not only [a] cold business relation.”

In 2015, shortly after the then presidential candidate’s anti-Muslim comments sparked outrage, Damac removed a Trump sign and a billboard of Donald and Ivanka Trump from the Damac Hills site.

The sign was taken down for “periodic maintenance” and put back up two days later, McLoughlin said. Still, Forbes reported that the billboard was replaced with one of Marlon Brando as Vito Corleone in “The Godfather.”

During a Sajwani family visit to Mar-a-Lago in Palm Beach, Trump called them “beautiful people.” During his presidency, he said he turned down Sajwani’s $2 billion real estate business proposal, but didn’t specify what the proposal was.

The Trump brand “carries significant weight in the global golfing community,” and Damac holds the “collaboration with them in high esteem,” McLoughlin said in his email.

Damac has no Trump partnerships in the pipeline, although Sajwani has said in interviews he is keeping an open mind.

Big Damac in little Surfside

Dubai’s property market is among the world’s most volatile. The city has seen housing prices plummet more than 25 percent since a 2015 peak in part due to oversupply, according to a JLL report cited by the Wall Street Journal. This year, the high-end housing market has rebounded, but Sajwani has cautioned that a slight improvement isn’t a reason to go all-out building.

“The situation does not look rosy,” he said last year, vowing that Damac would reduce construction and encouraging his competitors to do the same.

It’s possible that Damac sees South Florida as a potential bonanza. The region’s luxury market has been going gangbusters, with developers reporting a rush of sales. In August, Miami-Dade condo sales – excluding new development – rose by about 70 percent compared to August 2020 and about 65 percent compared to August 2019, according to the Miami Association of Realtors. Wealthy enclaves like Palm Beach and Miami Beach have been consistently breaking price records.

“It does not surprise me at all that Damac may want to tap into another market that may be similar to what Dubai was 10 years ago,” Poliakoff said.

As the stalking horse bidder, Damac set the minimum price for the Surfside collapse site. It will soon kick off its 90-day due diligence. Competing offers must begin at $120.3 million, and a court auction in late February or early March will determine the winner.

Surfside commissioners were looking to downzone the site as part of a townwide code revision, but ultimately allowed rebuilding up to Champlain’s size. That tower was 12 stories tall and contained 136 units, but the specifics of the redevelopment have yet to be hammered out.

“In Surfside, they’re going to have to deal with the zoning criteria being very strict,” said Reinaldo Borges, a Miami-based architect who worked for Damac and had an office in the Middle East for a decade leading up to the crash.

Champlain Towers South (Getty)

If Damac ends up purchasing the property, former residents of Champlain likely won’t be able to afford units in the new tower. At newer oceanfront developments in Surfside, units can run north of 8,000 square feet.

“I could only expect them to do something extraordinary in terms of quality and execution,” Borges said.

Recent sales at luxury projects in Surfside could provide a hint as to what pricing Damac may target. At the Four Seasons-branded Surf Club development, for example, sale prices have approached $4,000 per square foot. And even though the Champlain Towers site may have a stigma associated with the tragedy in the short-term, observers expect that to fade away over time.

“If the market was incredibly weak, the stigma would last longer because there would be many other alternatives,” said Jonathan Miller, head of appraisal firm Miller Samuel and author of Douglas Elliman’s residential market reports. “The fact [is] that the market continues to be very tight.”

Surfside could also be a key maneuver in Sajwani’s larger ambitions for Damac.

The billionaire is looking to privatize the company, offering $595 million for outstanding shares to be purchased through his holding company Maple Invest. The Sajwani family are majority shareholders and are deeply involved in the business: Sajwani’s son, Ali, is general manager of operations, and his daughter, Amira, is general manager of sales and development.

Sajwani might be looking to take the company private while the stock is cheap, and go public again down the line for a higher price, according to David Trainer, a corporate finance consultant. And Surfside may have a role to play.

“If they can get this asset at what they believe to be a cheap price and make a profit out of it, that would be one of the potential drivers to reverse losses into profits,” Trainer said.

Could a public offering in the U.S. be part of the plan? To pull that off, “they might have to have some presence, have some business in the United States,” Trainer said. “But it’s pure speculation.”

Damac’s foray into the U.S. may pave the way for other deep-pocketed developers from the Middle East who specialize in luxury projects, especially in lifestyle markets like Miami.

“It was only a matter of time before these developers started stepping into new markets and taking their learnings, their experience, their reputation with them,” said Durrani of Knight Frank. “This might be the start of a trend where we see more Middle East developers becoming active elsewhere in the world.”