Nicolas and Lourdes Padron never imagined having to leave the Hammocks, a suburban Miami enclave that was their home for three decades.

Then the threatening letters began.

The Hammocks Community Association claimed the couple owed thousands of dollars in arrears on assessments and that their house wasn’t up to its standards. The driveway was the wrong color, a tree needed pruning and the hurricane shutters weren’t up to code, one letter said.

“It was $1,000 for this, another $1,000 for that. They just threw amounts,” Lourdes Padron said. “We were constantly harassed.”

The couple tried to disprove the violations before the homeowners’ association sent them a statement in February claiming they owed $4,335. Threatened with foreclosure, they paid, sold their house and moved.

Residents at the Hammocks, home to South Florida’s biggest HOA, had complained for years of mismanagement by association leaders and opaque financial statements. Authorities started poking into it around 2017, according to court records.

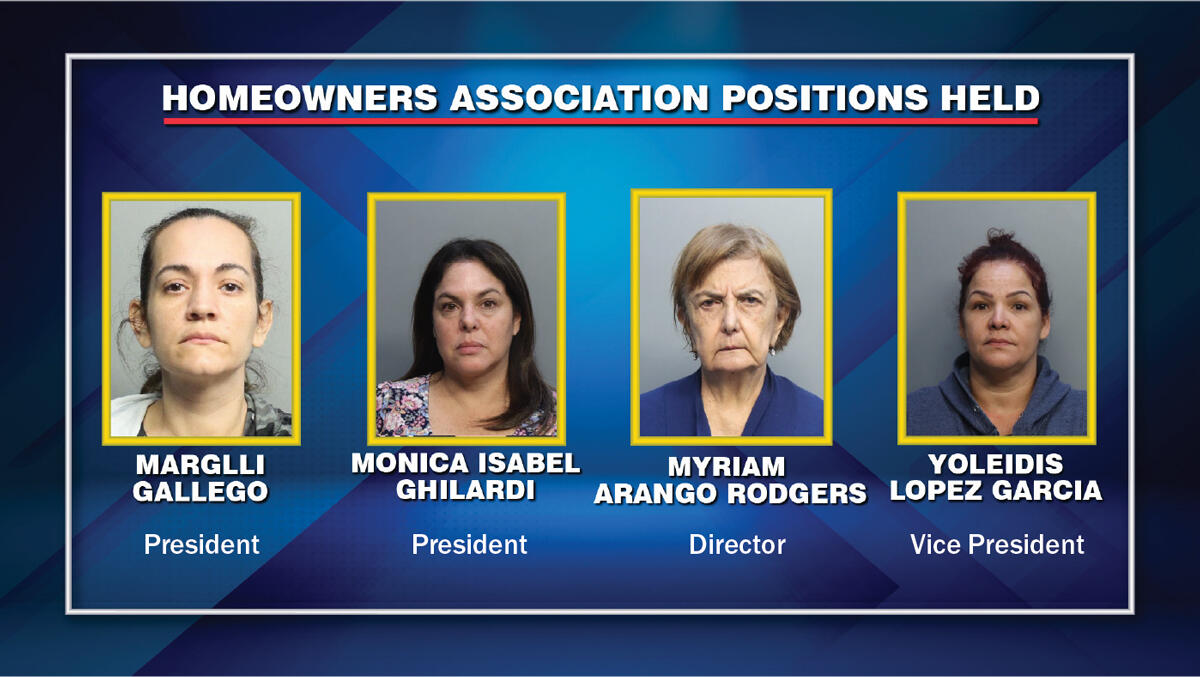

It would take five years until the Hammocks leadership collapsed. In November, police arrested four ex-board members and the husband of a former board president, alleging they looted roughly $2 million from association coffers.

As criminal investigators and a court-appointed receiver now overseeing the HOA try to untangle an alleged web of financial deceit, authorities have warned more arrests could be coming.

The case struck a chord with communities that suspect their boards are engaging in fraud. It also illuminates the shortcomings of the state’s HOA law.

While the law provides routes for legal action, it puts the onus on homeowners to react instead of giving a government authority the power to prevent fraud before it happens, according to attorneys. Residents can get discouraged, since they would have to ante up for litigation, while the boards’ attorneys are bankrolled through homeowners’ dues.

“It really is the perfect recipe for fraud,” said Dan Small, a white-collar crime attorney.

It’s an HOA. No, it’s a city

Marglli Gallego rode to power at the Hammocks in 2015. Some residents viewed her as a savior from previous board members they disliked.

But investigators allege Gallego turned out to be far from righteous.

They say funds were siphoned from HOA coffers and through five companies — two led by Gallego’s husband, Jose Antonio Gonzalez, who also is charged. The companies allegedly posed as service providers and vendors to the Hammocks, according to a November arrest affidavit. In one example, Gonzalez’s Excellent Work & Services received over $1.1 million from the HOA starting in 2016, the affidavit says.

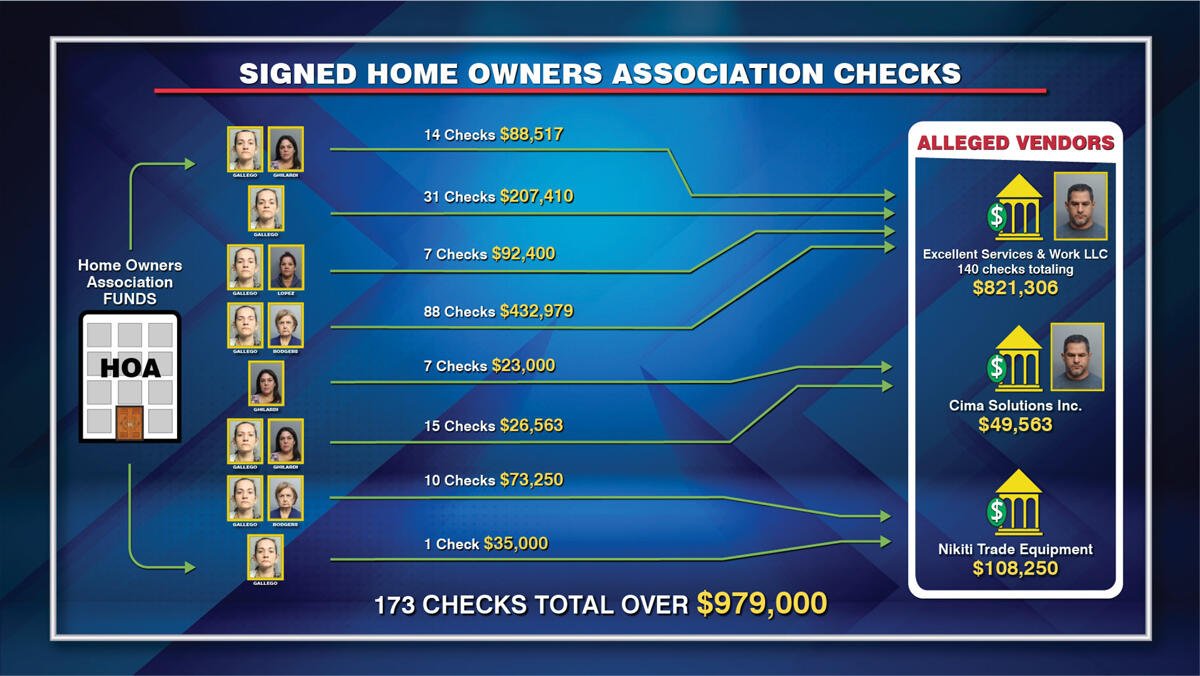

Gallego, 41, signed many of the checks to the vendors, as did other ex-board members charged: Myriam Rodgers, 77; Monica Ghilardi, 52; and Yoleidis Lopez Garcia, 47, the affidavit says. Much of the money allegedly went into the pockets of Gallego and Gonzalez.

Roberto Trueba, who led the other three companies through which funds were funneled, started out providing legitimate services until Gallego handed him checks for no work, Trueba, who is cooperating with investigators, told authorities last year, according to the affidavit. He said he cashed the checks, kept some for himself and handed the rest to Gallego or to Excellent Work. Once, Trueba said, he was asked to wire funds to a bank account in Gallego’s name in her native Colombia.

Attorney Sebastian Jaramillo said it is as if the board members didn’t try to mask their alleged chicanery.

“The fraud to me seems very unsophisticated. It’s a situation where she is paying to her husband’s company, which is domiciled in her own addresses,” he said, referring to Excellent Work. “There isn’t even any attempt to hide it.”

Gallego, who was first arrested last year on claims that she misappropriated funds, faces new charges. She and Gonzalez are accused of racketeering, grand theft and money laundering.

All five defendants have pleaded not guilty. Their attorneys either declined to comment or didn’t respond to a request for comment, except for Gonzalez’s lawyer.

“We are very curious to see what they [authorities] have to support those allegations, especially as it pertains to Mr. Gonzalez,” Jude Faccidomo said.

The Hammocks encompasses over 6,500 single-family houses, apartments and townhouses. It’s home to over 18,000 residents, spanning 3,800 acres between Southwest 120th and 88th streets and between Southwest 147th and 162nd avenues.

Therein lies the issue, said Small, of the law firm Holland & Knight.

The Hammocks is far bigger than the traditional HOA that the state law was crafted to target. Association leaders were left in control of a community larger than some cities, without the oversight that would exist in an actual municipality.

Case in point: Residents said the board imposed a 400 percent assessment hike in March.

“If the city council of the Hammocks, say it were organized that way, voted to raise taxes by 400 percent, it just wouldn’t happen,” Small said. “Yet that’s exactly what this association did.”

Slides presented by the Miami-Dade State Attorney’s office identifying the Hammocks HOA officers and detailing payments allegedly made to companies posing as vendors.

A threat and private eyes

Some Hammocks residents said the more they spoke out, the more the former board retaliated.

After Eldridge “Manny” Coburn signed a petition this year to recall the board, “all hell fell through,” he said. The HOA barred him from using amenities, saying he was overdue on assessments. Coburn said he was paying on time.

The recall effort came after the association closed polls early in January, citing a bomb threat. Investigators say the HOA never provided proof of this.

In legal filings, the HOA and Gallego claim they are the true victims.

Investigators issued three subpoenas for financial records, which amounted to over a million pages of documents and were “outrageously burdensome,” the HOA claims in a lawsuit filed this year against the state attorney’s office. An HOA attorney told a judge that the board refused to comply because it “doesn’t trust the state,” filings show.

Gallego claimed she was a passionate leader of the Hammocks who spearheaded free activities such as after-school tutoring and Zumba classes, according to a suit she filed against Miami-Dade police officers who were investigating her. She claimed her “political opponents” led a campaign against her, culminating in death threats. The association was therefore within its right to pay for a surveillance firm at the Hammocks, Gallego’s lawsuit claims.

The HOA tapped into the Hammocks’ budget for many of its legal fights, according to the November arrest affidavit. For Gallego’s four criminal defense attorneys, the HOA has shelled out more than $250,000, according to the affidavit.

No one to turn to

State law takes a hands-off approach to HOA oversight, but the Hammocks case shows this isn’t working, said real estate attorney Lauren Fallick.

The law mandates annual financial audits, which the Hammocks allegedly ignored starting in 2018. Yet the statute requires HOAs to provide the reports only once a records request is made, rather than requiring that they be submitted annually as proof they were completed, experts said.

Residents in dispute with the HOA can pursue mediation or sue — but at a cost, according to Avi Tryson, a real estate and HOA attorney.

“This is still a legal expense for the residents for the hourly rate for the mediator and whoever is their attorney at the mediation,” he said.

Following the Hammocks arrests, elected officials have called for a tightening of the law.

Meanwhile, the Padrons have made Tamarac their new home.

“You didn’t know what kind of threats were going to come next,” Lourdes Padron said. “We were forced to leave.”

Read more