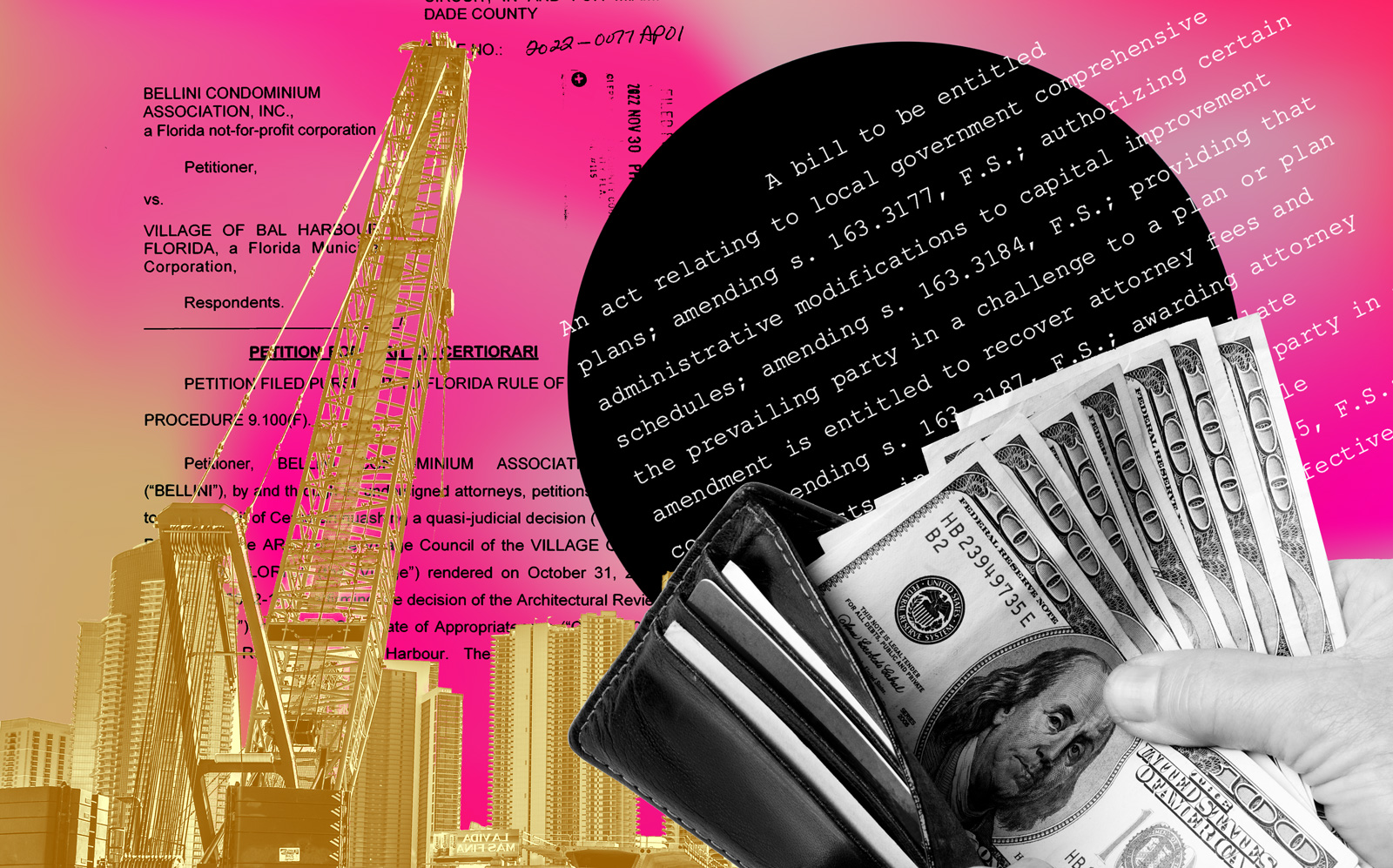

Florida’s proposed affordable housing legislation, aimed at incentivizing developers with major tax breaks and hundreds of millions of dollars in funding, is advancing in the state legislature.

Senate Bill 102, known as the “Live Local Act,” and related legislation would be a boon for developers of attainable and workforce housing, real estate attorneys and developers say. The bill was approved by the community affairs and appropriations committees in February, and heads to the senate floor next. If it becomes law, it will take effect July 1.

Florida Sen. Alexis Calatayud, a Republican who represents part of Miami-Dade County, introduced the legislation in January. It aims to create more affordable rental housing via tax breaks, expedited permitting, funding and zoning incentives. It also would restore funds to the Sadowski Trust Fund, which has been gutted by Florida lawmakers for years.

Opponents are critical of some aspects of the legislation, including the state eliminating the ability of local governments to enact rent control. That is currently only allowed if local governments declare a housing emergency.

Land use lawyer Debbie Orshefsky, based at Holland & Knight’s Fort Lauderdale office, said it marks the first time Florida takes a “comprehensive approach to addressing the affordable housing crisis.”

More than 2.1 million low-income households in Florida spend more than 30 percent of their incomes on housing, and over half of those households spend more than 50 percent of their incomes on housing, according to the Florida Housing Coalition.

South Florida became one of the least affordable housing markets in the country last year, following large gains in home prices and rents during the pandemic. Miami-Dade County Mayor Daniella Levine Cava declared a housing emergency in April, and later distributed millions of dollars in federal rental assistance funds.

If the proposed legislation passes, local governments would have to maintain an online inventory of affordable housing properties. They would also be required to expedite building permits, which some already do.

The bill also preempts local governments’ zoning, density and height requirements of affordable housing, in areas zoned for commercial or mixed-use development. That means such developments may not require zoning changes or comprehensive plan amendments. Local governments would be required to allow multifamily and mixed-use residential in any commercial or mixed-use zone if at least 40 percent of the residential is affordable for at least 30 years. With projects allocating at least 65 percent of the square footage to residential, a county would not be able to restrict the height of a proposed development below what’s currently allowed within one mile of the planned project.

In addition to providing new sources of funding for low income housing tax credit developers, the legislation “will also allow market-rate rental developers to actually incorporate some affordable units in their market-rate developments,” Orshefsky said.

Market-rate developers who include workforce housing units in their developments could qualify for ad valorem tax exemptions. Developers setting aside at least 70 units for people earning 120 percent of the area median income or less, in newly completed or substantially renovated properties, could qualify.

Orshefsky said that if the bill becomes law, her market-rate developer clients will consider setting aside units for affordable housing.

Tim Wheat, a partner at Miami-based Pinnacle Housing, said the prospect of providing exemptions for developers building units for people earning between 80 percent and 120 percent of the AMI, which he referred to as the “missing middle,” is key. Property taxes could account for 25 percent of a developer’s operating cost on a per-unit basis, he said.

“Now developers that are doing market-rate projects in urban areas are going to look at this potential tax exemption, they’re going to look at their pro formas, and say ‘Hey, maybe that’s worth it for us,’” he said. “It’s a way for the private market to solve a problem there really is no solution for.”

The affordable housing arm of Miami-based Related Group has thousands of units it would finance under the proposed legislation “once it becomes law,” said Albert Milo, president of Related Urban, via a spokesperson. The firm has more than 10,000 units in its development pipeline in Florida.

Also under the bill, local governments can offer property tax exemptions to developers who set aside units for households earning 60 percent of the AMI. Land owned by nonprofits leased for at least 99 years could also receive the property tax exemption.

Increased funds

Attorney Keith Poliakoff, of Fort Lauderdale-based Government Law Group, said the state’s existing affordable housing funds are currently “woefully small, based upon the need.” Florida Housing and Finance Corporation only approved one project in Broward County for 2023, he said. FHFC administers the state’s SAIL (State Apartment Incentive Loan) and SHIP (State Housing Initiatives Programs).

But under the proposed law, the amount of affordable housing funds would grow exponentially.

“This landmark legislation is the first of major consequence to help ensure affordable housing will be built,” Poliakoff said. “It takes a lot of the handcuffs off the developers who develop this type of housing.”

Under the proposed legislation, up to $150 million would be allocated to SAIL; another $109 million from the State Housing Trust Fund would be directed to SAIL; $100 million would go to the Florida Hometown Heroes Program; $252 million to SHIP; and $100 million in non-recurring funds would be set aside for a competitive loan program that developers could tap to cover inflation-related cost increases for FHFC-approved multifamily developments that haven’t broken ground yet.

The legislation also increases the amount of tax credits available through the Community Contribution Tax Credit Program for affordable housing to $25 million annually, from $14.5 million. And it provides up to a $5,000 sales tax refund for building materials used for affordable housing units.

The Hometown Heroes homeownership assistance program, which was created last year, allows some buyers to finance home purchases with no-interest loans to reduce their down payment and closing costs to a maximum of 5 percent or $25,000, whichever is less. Buyers who qualify have a household income of no more than 150 percent of the state or local AMI. The law would codify the program and expand eligibility to more people, according to the Senate’s analysis.

Poliakoff said a number of projects that his developer clients are working on are approved, but are on hold due to funding gaps. The growing cost of construction has also affected affordable housing builders. Wheat, of Pinnacle, said the cost of insurance has gone up as much as 40 percent.

Miami-based Housing Trust Group, led by Matthew Rieger, is missing about $3 million for the second phase of a development in Deerfield Beach called Tallman Pines, said Dilia Tabora, HTG’s vice president of development. The Broward County Housing Authority has been trying to redevelop the site for years. HTG also has a 320-unit planned development in Naranja Lakes near Homestead. The developer is looking to secure about $4 million in funds to move forward on the project.

“We have funding, but with the construction costs and the insurance costs you never know if it’s going to end up where it will,” she said. The property tax exemption, Tabora added, would be “insanely helpful” for developers.

Read more