A pair of bills making their way through the Florida Legislature could fuel a deluge of property sales and demolitions of historic properties in coastal cities, including Miami Beach and Palm Beach.

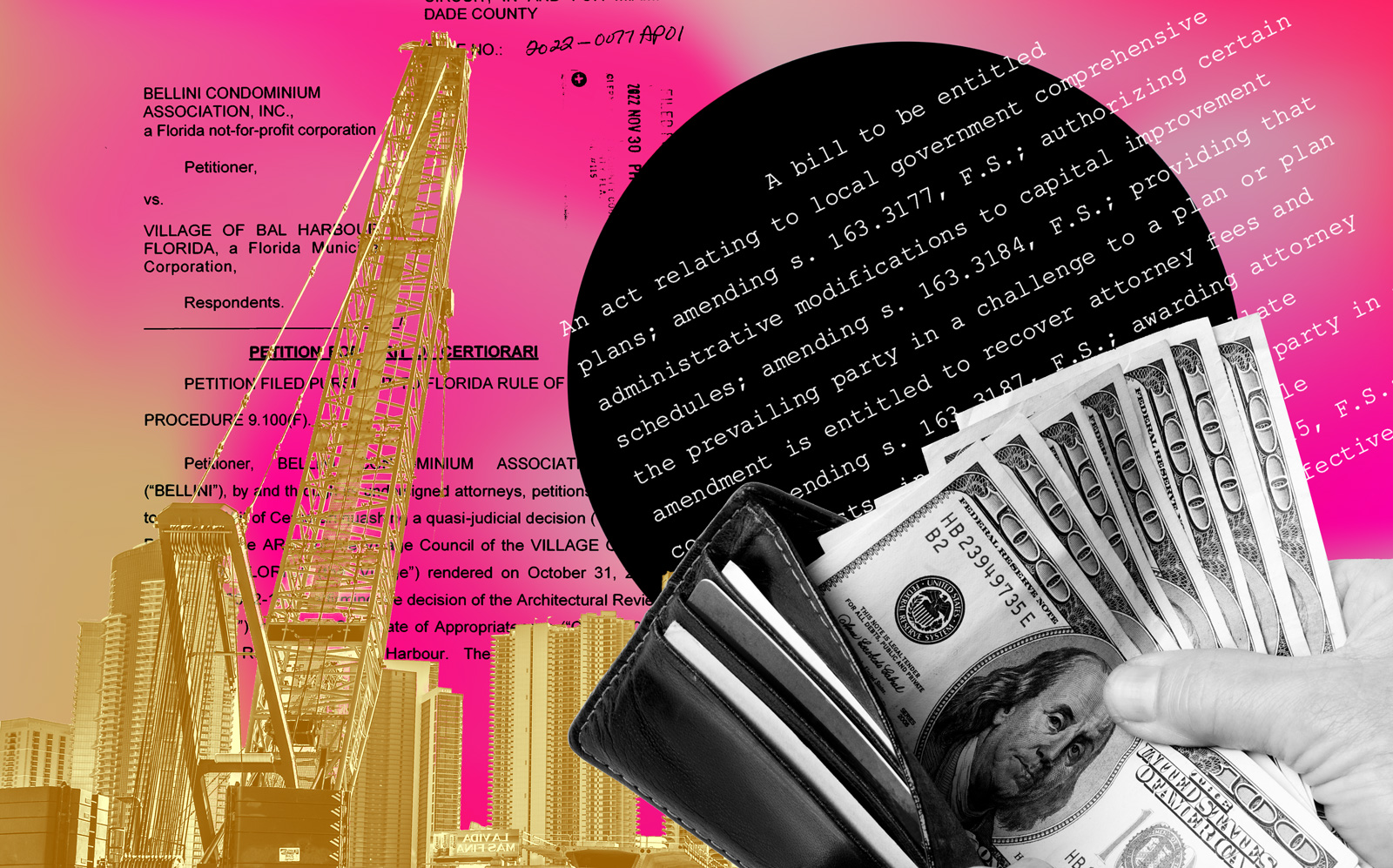

If the bills become law, Florida Senate Bill 1356 and House Bill 1317 would strip local municipalities of their authority to determine if certain structures can be demolished, and what could be built in their place. Sen. Bryan Avila, a former Hialeah planning and zoning board member who represents part of Miami-Dade County, and Rep. Spencer Roach, who represents DeSoto County and parts of Charlotte and Lee counties, are sponsoring the sister bills.

The proposed legislation would be a boon for developers.

It would allow owners and developers to demolish “non-conforming” properties within a half mile of the coast and within specific flood zones — regardless of whether the buildings are in a historic district. Non-conforming buildings are any that do not meet new construction requirements under the National Flood Insurance Program.

Single-family homes are exempt. The only other structures that would be exempt under the Resiliency and Safe Structures Act are those individually listed in the National Register of Historic Places. It could affect coastal cities up and down the coast, from Fernandina Beach to Key West.

That means properties in historic districts would not be protected, even if those districts are part of the National Register.

Daniel Ciraldo, executive director of the Miami Design Preservation League, which opposes the legislation, said that only seven properties in Miami Beach are individually listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Thousands are in historic districts.

“It would lead to a rash of speculative purchasing of historic buildings and demolitions,” Ciraldo said about the proposed bills. One example of that could be the historic Art Deco buildings on Ocean Drive, he said. No individual properties are on the register.

Ciraldo called the legislation “very troubling” and “an affront to historic preservation standards.”

Cities across South Florida have historic preservation boards that oversee land use and zoning rules over historic districts and properties. The Miami Beach Historic Preservation Board, for example, has authority over approvals in the city’s historic districts, including along Collins Avenue. The board has overseen project approvals for developers Michael Shvo and Vlad Doronin, who each have oceanfront towers planned next to their historic buildings.

Over the past couple of years, a battle has ensued regarding which properties should be preserved and if buildings must be replicated if they are demolished due to life safety concerns. The issues followed the deadly condo collapse in Surfside in the summer of 2021.

Billionaire developer Steve Ross, owner of the Miami Dolphins and chairman of New York-based Related Companies, sought approval of a larger development than is currently allowed on the site of the now demolished Deauville Beach Resort, but failed to garner enough support. Ross was in contract to buy the property from the Meruelo family, which many argue let the historic hotel fall into disrepair to the point that it could not be saved.

At the time, historic preservation board members warned the “demolition by neglect” would set a dangerous precedent for owners of historic properties: It could allow forced demolitions when otherwise owners would have to preserve architecturally significant structures.

Critics say the proposed legislation is too broad because it calls all buildings that were not built to current flood insurance standards “non-conforming.” If the bills become law as currently written, the measure could render many historic board decisions moot.

Said Ciraldo: “We don’t want to take a shotgun to kill a flea.”

Read more