It’s a situation that leaves experts scratching their heads.

Miami-Dade County is one of the hottest real estate markets in the country. The pandemic fueled a surge in demand for homes in the region and set the luxury residential market ablaze with back-to-back record-breaking deals and an unprecedented pace of sales. While the market has since cooled off, prices are still growing in the county.

It’s also the riskiest U.S. county for insurance companies, according to data from CoreLogic, an Irvine, California-based analytics firm. In response to the growing risks, providers continue to raise their rates, causing insurance premiums to skyrocket. But it doesn’t seem to be deterring buyers in the residential market.

“It’s definitely a hot conversation subject,” said Dina Goldentayer of Douglas Elliman. “But then again, insurance has always been high in South Florida compared to other markets.”

In fact, Florida is the most expensive market for homeowners insurance, according to Insurify. Average premiums in Florida reached $6,000, which is more than three times the national average of $1,700, according to the Insurance Information Institute.

As of September, the average rate charged for insuring a single-family home in Miami-Dade County was $5,919, up from $5,391, year-over-year, according to data from the Florida Office of Insurance Regulation. In Broward County, the average cost was $5,911, and in Palm Beach County it was $6,124. Part of the higher cost is the myriad policies most homeowners in the region need to have –– general risk and fire, as well as wind and flood policies. Wind policies are particularly pricey, agents say. Mortgage companies require wind coverage, but homeowners who pay cash or who have paid off their mortgages are not subject to that requirement.

“Many of my buyers who are paying cash, they tend to forgo wind, which is the most expensive,” Goldentayer said.

Rapidly rising residential sale prices in the nation’s riskiest market, (from an insurance perspective), is the perplexing phenomenon CoreLogic’s chief innovation officer John Rogers calls the “Miami paradox.”

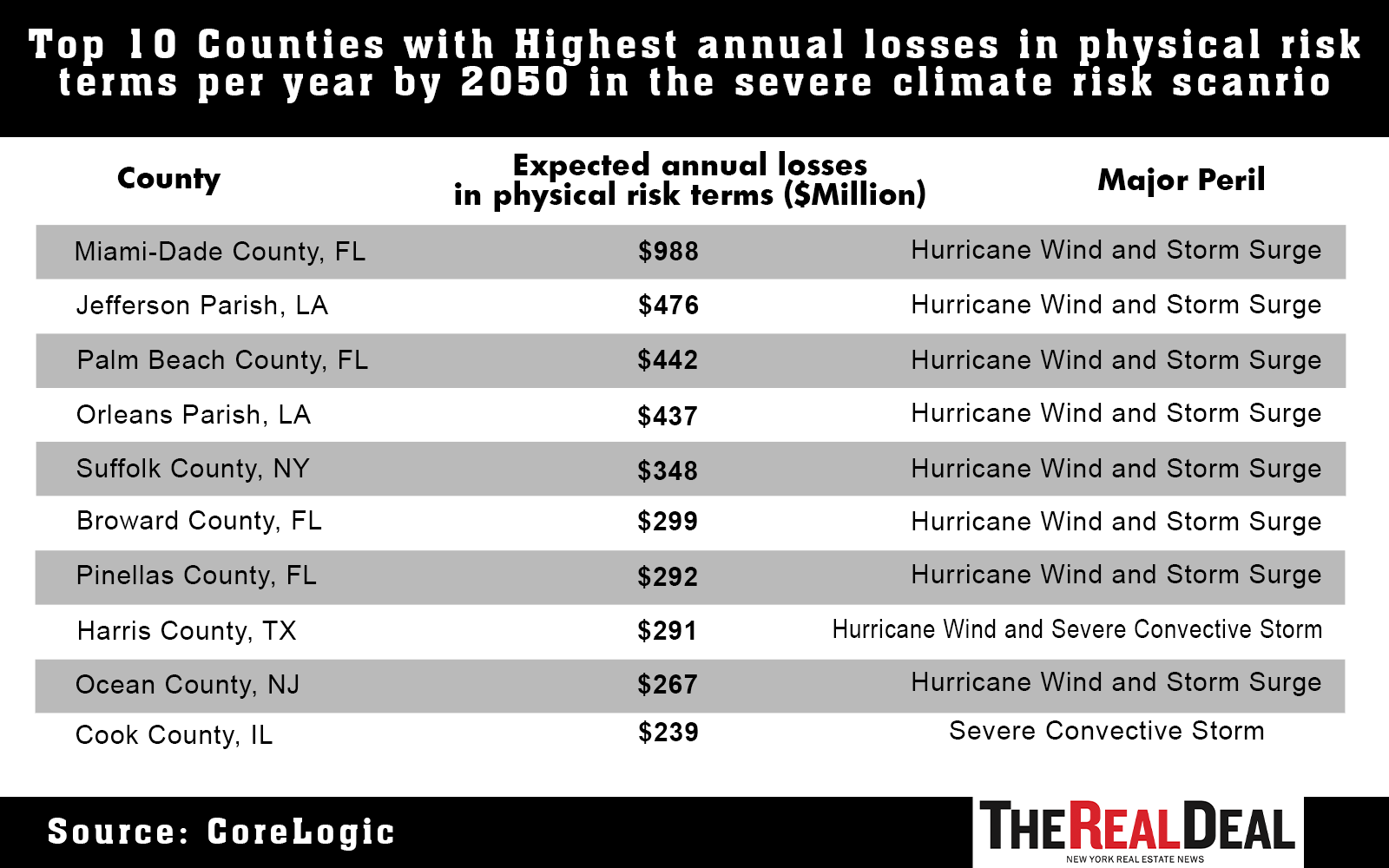

CoreLogic projects that Miami-Dade County will experience an average of $988 million in annual property losses per year by 2050 with severe climate change. The next riskiest county, Jefferson Parish in Louisiana, is expected to face $476 million in average annual property losses –– about half of the damages anticipated for Miami-Dade.

All these losses are going to hit insurers’ bottom lines, Rogers said.

“The risk level is rising rapidly,” he said. “For insurers to price correctly, unfortunately they need to increase [rates] right now.”

Many insurers have abandoned the market altogether, rather than play the game of accurately pricing climate risk. In October, Progressive announced it was dropping 100,000 home insurance policies in Florida. In July, Farmers Insurance, citing a need to “manage risk exposure,” said it would stop writing and renewing policies in Florida, impacting an estimated 100,000 home insurance policies.

With many providers leaving the state, many homeowners have increasingly had to turn to Citizens Property Insurance, the state-backed insurer of last resort. Citizens was formed in the aftermath of Hurricane Andrew in 1992, then the costliest storm to ever hit the U.S.

Its enrollment has ballooned in recent years –– policies reached 1.2 million in January, up 110 percent from January 2021, according to policy data from Citizens. That was the year the pace of enrollment started a dramatic uptick. The insurer’s policies peaked in September, when it reported a record 1.4 million policies, and planned for an 11.5 percent rate hike for its most popular homeowners plan.

“A lot of people would say Florida is a market in crisis,” said Tom Larsen, a senior director for insurance solutions at CoreLogic.

Miami isn’t the only market where insurers are struggling to correct their rates to account for climate risk. A report released in September by First Street, a New York City-based research firm, estimated more than 39 million homes have policies that were underpriced for the climate risk they face.

“Ultimately, as houses get affected by these major weather events, the cost of replacing that house far outweighs the incremental adjustment on someone’s policy,” Rogers said. At a certain point, homes in high risk areas could lose their value. “I know it’s a painful part but we’re going to have to face up to it.”

When asked if her buyers are concerned about the impacts of climate change, Goldentayer said, “Uh, no.”

“They’re focused on the lifestyle benefits, they’re focused on the economic benefits,” she said. “They’re not asking about sea level rising.”

Read more

Carlo Dipasquale, an agent with Compass in Miami, said he recommends researching elevation levels for properties and buying new construction homes, which are typically cheaper to insure.

“You can never go wrong when you’re buying a new house,” he said.

If anything, buyers use rising insurance costs to negotiate, Goldentayer said.

“I think this dynamic gives buyers further leverage in our marketplace,” she said. “Buyers do use this to get a better deal.”