UPDATED: June 27, 12:23 p.m. Something about this moment seems all too familiar. Prior to the financial crisis, small mortgage companies were lending to thousands of homeowners throughout the country with the backing of credit lines from the largest banks. Now, more than a decade later, nonbank lenders are once again ramping up their mortgage lending in the U.S. and South Florida with credit lines from America’s largest financial institutions.

These nonbank lenders such as Quicken Loans, Freedom Mortgage and loanDepot claim they aren’t making risky loans, but are instead filling a void by offering home mortgages in just a few days instead of the weeks that it would take banks to issue such loans.

At the same time, local banks have also pulled back from originating residential mortgages. Take for example South Florida’s largest bank, Miami Lakes-based BankUnited, which announced in 2016 that it would no longer originate residential mortgages. Other banks across the country, including HomeStreet Bank in Seattle, are backing away from the mortgage business. Doral-based U.S. Century Bank said in 2018 that it would “outsource” its residential lending to a third-party provider.

Raj Singh, the current CEO of BankUnited, said residential mortgages are a low-margin business that is very competitive. Profits are highly dependent on interest rates.

“I think it’s tough for regional banks with residential lending… at best you will break even,” he said.

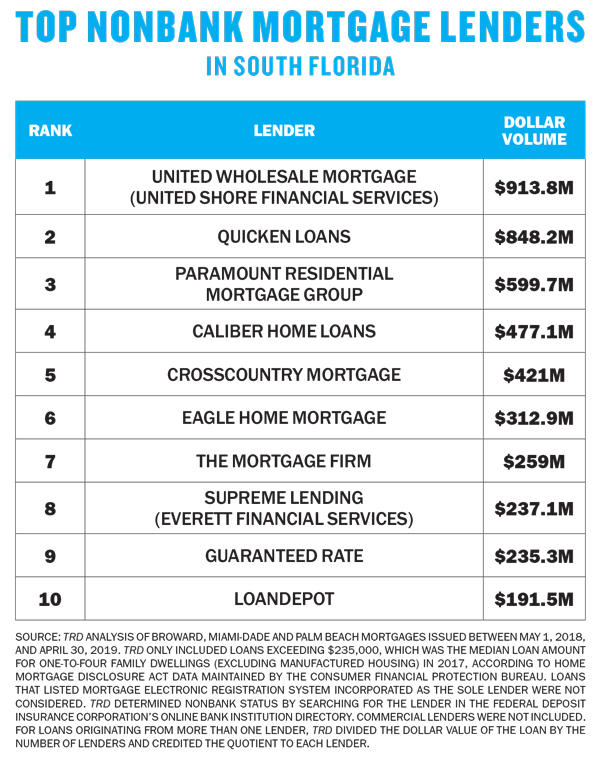

In South Florida, nonbank lenders now take up a majority of the market share of mortgages in South Florida between $250,000 and $500,000, according to research from The Real Deal.

The five largest nonbank lenders provided nearly $2.9 billion in residential mortgages in South Florida between May 1, 2018, and April 30, 2019. Meanwhile, the five banks that issued the highest dollar volume in mortgages provided just $1.47 billion during this same time period, according to TRD’s research.

To rank the biggest nonbank mortgage lenders in South Florida, TRD analyzed Broward, Miami-Dade and Palm Beach mortgages issued between May 1, 2018, and April 30, 2019. The data only included loans exceeding $235,000, which was the median loan amount for one-to-four family dwellings (excluding manufactured housing) in 2017, according to Home Mortgage Disclosure Act data maintained by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

While some say nonbanks are filling a need to low-income and moderate-income borrowers, critics wonder whether these new entities are taking on too much risk and could run into liquidity issues if the economy were to head into a recession, leaving the government to clean up the mess.

“Banks have capital, so the federal government targeted them because, unlike most non-banks, they had the money to pay big fines,” said Edward Pinto, a co-director of Housing Markets and Finance at the conservative think tank AEI. “The nonbanks just don’t have those type of assets.”

The rise of the nonbank

Nonbank lenders rose to prominence after the financial crisis, when the largest banks such as JPMorgan and Bank of America were dealing with the ramifications from their pre-crisis lending.

“There was a major pullback from major banks in mortgage lending. A lot of it is due to the fact that there was a huge amount of litigation and settlements,” said Pinto.

Banks that were still making these loans were especially reluctant to issue FHA loans to low-income borrowers. In Miami, many of the local banks became more focused on making higher margin loans to high-net-worth individuals, despite being required under the Community Reinvestment Act to lend to the community.

In one case, regulators found Miami-based Helm Bank to have made no home mortgage loans to low-income and moderate-income borrowers in 2014, 2015 and 2016, according to the FDIC.

“Companies like Quicken stepped into the breach to become national lenders. They really weren’t scared to go down on credit scores,” said Ted Tozer, the former president of Ginnie Mae from 2010 to 2017. Tozer is currently a senior fellow at the Center for Financial Markets at the Milken Institute.

Tozer called these nonbanks “one trick ponies” that were able to devote all of their resources and money to making the mortgage process more efficient. Detroit-based Quicken Loans — second in the ranking, with $848.2 million in mortgage loans issued — became one of the most well-known and successful nonbank lenders through its online platform called Rocket Mortgage, which claimed it could close on a mortgage in eight days.

The service has also been a huge boost of revenue to Quicken Loans’ parent company, Rock Ventures, which had more than $6 billion in sales in 2018, according to Forbes.

Alternative lenders accounted for almost half of mortgage originations in the U.S. in 2016, up from about 20 percent in 2007, according to the Brookings Institute.

In many ways, nonbanks provide consumers sometimes with access to better rates, according to Marc Halpern, who leads the Miami Beach-based mortgage brokerage Halpern & Associates, which does business across South Florida.

“My take on it is the nonbank lenders are really good for competition,” Halpern said.

During his tenure at Ginnie Mae, Tozer was beginning to notice that some of these new lenders that were filling this void were also taking on a lot of risk.

Many of these nonbank loans were guaranteed by Ginnie Mae, and Tozer worried about what would happen if the economy soured and borrowers started to fall behind on their loan payments.

These nonbanks will still have to service these loans, meaning that they would have to make interest payments on the loans until they go into foreclosure. Nonbanks don’t have access to the same government resources as banks, and if lenders pulled back on their financing, nonbanks could run out of cash to keep making loans.

“The issuers that we had to deal with, they weren’t insolvent, they ran out of cash,” Tozer said.

To observers of the financial markets, this may sound familiar. Investment banking powerhouse Bear Stearns collapsed in 2008 not from insolvency but because of a run on the bank. Bear Stearns investors started to pull their money out of the banks, and the bank ran out of cash before JPMorgan bought it for $2 a share.

Researchers from the Federal Reserve and the University of California Berkeley highlighted these points in an article for the Brookings Institute in 2018. Echoing Tozer, the report states that the issue could be liquidity strains if bank credit lines start pulling back financing.

“The typical non-bank has few resources with which to weather these shocks,” the report said. “Non-banks with servicing portfolios concentrated in Ginnie Mae pools are exposed to a higher risk of borrower default and higher potential losses in the event of such a default.”

Wary of warehouse lines

Singh, the CEO of BankUnited, said his bank is one of the banks providing the line of credit to nonbank lenders, which are referred to as warehouse lines.

Banks generally ask the nonbank lenders to provide the mortgage as collateral and then collect revenue after the mortgage is sold off.

Singh said the risks with these warehouse lines are twofold.

“One is operating risk, and day-to-day businesses,” said Singh. The other, he said, is looking at the quality of the underwriting.

Large banks could be exposed to large losses if a nonbank fails because these credit lines could be written down.

By the end of 2016, the largest bank holding companies had financed warehouse loans totaling $34 billion, up from $17 billion at the end of 2013, according to the Brookings Institute paper.

Josh Migdal, an attorney with Miami-based Mark Migdal & Hayden, said that these nonbanks are threatened when warehouse lenders re-price their lines of credit and borrower delinquency increases.

“To stave off insolvency, nonbanks will need to expedite the foreclosure process to stop the bleeding that will be caused by having to fund servicing advances while a loan is in default,” he said.

Since these nonbanks are the largest providers of these loans, a widespread collapse of this industry could be devastating to the housing market. If nonbanks stopped lending, it could create a domino effect where home buyers would not be able to get a loan.

“If that does happen, then mortgage bankers have to start hoarding cash, then they are not going to make new FHA or VA loans,” Tozer said.

While some are concerned about the rise of nonbanks, others aren’t so worried. Instead, they say that mortgage lenders — both bank and nonbank — are more conservative this time around. Lenders aren’t making the same no-money-down type of loans, and new rules require much more evidence around proof of income.

“You have to show the ability to repay… You have to show your W2 and tax returns,” said Halpern. “Post-2008, it is a requirement before [lenders] fund the loan to verify the tax returns.”

But if a recession arrives, borrowers buying homes at the end of the cycle would once again be hurt the worst, Pinto said. The issue is compounded by nonbank lenders, which are providing riskier loans than banks, which is allowing people to purchase homes that they ordinarily could not afford, he said. If borrowers start defaulting, it could quickly lead to major issues with nonbank lenders.

“Even with a small bank, you are not worried about them not being able to honor their obligations,” Pinto said. “You can’t say the same thing about nonbanks. They don’t have anywhere near that capital.”

Correction: This article has been amended to clarify the remarks made by Mr. Pinto.