For well over a decade, Turkish entrepreneur Mehmet Bayraktar has been on a seemingly quixotic quest to transform a barren patch of prime waterfront land in Miami into a billion-dollar ultraluxury resort with a supersized wharf accommodating the 1 percent’s titanic yachts.

But the mixed-use project known as Island Gardens, planned for city-owned property on the southwestern side of Watson Island, has been stymied by one obstacle after another from the get-go.

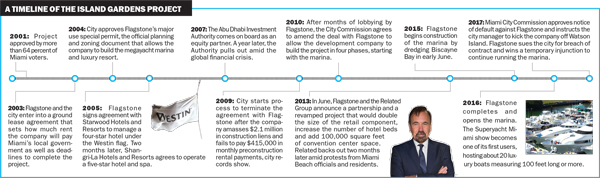

For starters, Bayraktar’s Flagstone Property Group claimed it was blocked from breaking ground on the project at every turn, citing everything from the economic fallout after 9/11 to the Great Recession as well as numerous lawsuits, some of them resulting from local opposition.

Along the way, potential partnerships with big brands like Sherwood Resorts and Hotels, Shangri-La Hotels and Resorts and the Related Group have fizzled.

The developer finally broke ground on the project — which consists of a high-end shopping mall, two upscale hotels, restaurants, parking facilities and a 50-slip marina — in 2015. But just when Bayraktar was really gaining steam with the completion of the $52 million marina last year, his landlord — the city of Miami — decided it was time to cut ties with Flagstone.

Now Bayraktar has one last chance, observers said. Flagstone is suing the city in an attempt to overturn a Miami City Commission vote in May that found the developer defaulted on the agreement by allegedly missing a key construction deadline. The case is set to go to trial in February.

Bayraktar did not respond to multiple requests for comment himself, but his representatives said the 56-year-old developer remains determined to build Island Gardens. “I don’t think he is going to walk away from his vision,” said Brian May, a principal with Miami lobbying firm Floridian Partners, who represents Flagstone before the city.

But opponents of the project strongly believe Bayraktar’s project is finished. They say there are numerous times his company failed to meet requirements in various agreements and leases with the city.

Stephen Herbits, a lawyer and former Department of Defense bureaucrat, is a local activist who has led the opposition against the development in various capacities for almost as long as Island Gardens has been on the drawing board. “I think he is just trying to save face,” Herbits said of the new lawsuit. “This is a huge personal defeat for him. Island Gardens will never happen.”

In the 15 years Herbits has opposed Island Gardens, he has accused city officials of repeatedly breaking their own rules to help Flagstone. And he was a key player recently in convincing city commissioners to kill the deal with Bayraktar’s company even though both City Manager Daniel Alfonso and the city’s Real Estate Asset Management Director Aldo Bustamante stated publicly that they believed Flagstone was not defaulting on its agreement with the city.

Flagstone Property Group fi led suit against the city of Miami after the developer was kicked out of Watson Island and the Island Gardens project.

In January 2017, Flagstone sued Herbits and one of the entities he was working with — the Coalition Against Causeway Chaos — for malicious prosecution and interference, but a Miami-Dade circuit judge dismissed the lawsuit this summer, saying the company had failed to establish a basis for its claims. Three weeks later, Flagstone filed an amended complaint.

“It suggests to me that their primary goal is to bankrupt me,” Herbits said. “I have been told Mehmet holds me personally responsible for ruining his project.”

The project’s origins

Bayraktar’s family ventured into real estate in the late ’70s with the construction of Turkey’s first indoor shopping mall, the Galleria Ataköy in the suburbs of Istanbul, according to the 2001 proposal Flagstone submitted to the city. Galleria Ataköy also has two hotels, waterfront restaurants and a marina, just as Island Gardens would. At the time of the proposal, Flagstone was one of three development teams that submitted bids to build on Watson Island.

Flagstone won the bid, and in November 2001, Miami voters approved the company to develop the project. But it would take another three years for Flagstone and Miami officials to hammer out the first of several agreements that laid out how much the company would pay the city in annual rent and the percentage of gross revenues to be shared with the local and state governments.

During the same period, Flagstone was going through the planning and zoning process to obtain approval for its major special use permit, the official document that would authorize the company to build the massive mixed-use development.

The City Commission approved the agreement in 2003 and the permit in 2004, but Flagstone faced delays over the next two years as a result of two lawsuits filed against the city by Herbits that challenged the permit approval, saying it was inconsistent with Miami’s master plan and zoning code. Both times, Flagstone intervened on the city’s behalf and beat Herbits in court.

In court documents, Flagstone claims that between 2006 and 2008, the company secured construction loan term sheets for the hotel component from United Mellon National Bank and the marina component from Bank of America and brought in the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority as an equity partner. But a year later, Flagstone’s lenders and the Authority backed out due to the global financial crisis, according to Flagstone attorney Eugene Stearns of Stearns Weaver Miller Weissler Alhadeff & Sitterson.

The company also amassed $2.1 million in construction liens against the property and failed to pay $415,000 in monthly preconstruction rental payments between 2004 and 2009, court documents show. Flagstone paid the rent it owed the city at the end of 2009, after officials threatened to cut ties with the company.

In 2010, city commissioners approved amendments to the agreement allowing the company to build the project in phases after Flagstone paid a one-time advance of $1.5 million in rent. At the time, Miami’s elected officials expressed reluctance to end the deal and start the entire process of bidding out Watson Island from scratch, according to meeting minutes of the City Commission and old press clips.

Mounting obstacles

Still, the company was unable to get Island Gardens off the ground for the next three years. Flagstone representatives insist that was due to the global recession.

Things took a brief positive turn in 2013 when the Related Group announced it was partnering with Flagstone on the project and sought to increase the size of the development by adding more hotel rooms, more retail space and a convention center. However, the partnership was short-lived. Related backed out two months after the announcement, when Miami Beach elected officials and residents threatened to file a lawsuit because the development had grown in size.

But Bayraktar soldiered on. In early 2016, he completed and opened the 50-slip marina after nearly two years of construction. He also briefly opened an outdoor dining and nightlife establishment — the Deck at Island Gardens — that was shut down in March after operating without a business license for nearly a year.

Along the way, Flagstone has intervened in at least a half-dozen lawsuits filed against the city by Herbits and other city residents who accuse Miami administrators of withholding key public documents and violating laws governing city contracts, among other things related to the controversial development. And each time, Flagstone prevailed against its adversaries.

But even winning came at a cost, said company lawyer Stearns. “It is difficult to get financing in this climate when you have to disclose all these litigations and alterations to the project,” he said. Yet he insists Bayraktar can complete Island Gardens with his own money if he has to.

The trial ahead

After years of helping to fight suits levied against Miami, Bayraktar now finds himself at odds with the city in court. His lawsuit hinges on whether he can prove Flagstone met a May 1, 2017, deadline to commence construction on the 221,000-square-foot mall and garage. In its June 9 lawsuit, Flagstone contended that it obtained permits to begin foundation work on the parking and retail component on Sept. 1, 2016, and that construction began shortly thereafter — eight months before May 1.

Flagstone and its representatives also point to communications with the city that state the company was not in default of any of the lease requirements. According to an email to commissioners days before their May 30 vote, the city manager wrote: “Given the information that I have seen, I would advise that they are not in default.”

But the opposition disputes many of those claims. Sam Dubbin, an attorney for Herbits and the Coalition Against Causeway Chaos, told commissioners during the May 30 meeting that, based on the city’s own permitting records, there was no way Flagstone met the deadline. Indeed, Miami’s online permitting database shows Flagstone allowed its foundation permit to lapse, forcing the company to apply for a new one on March 1, which would make the developer’s claim that it started work after receiving a Sept. 1, 2016, permit less credible, Dubbin said. He also noted that Flagstone’s ground lease required the company to have all the necessary permits, not just some, prior to construction on the retail and parking component.

Then-City Commissioner Francis Suarez, who was recently elected mayor, also argued during the May 30 hearing that Flagstone breached its contract with the city by failing to secure a mandatory construction loan before the city and the company signed a separate land lease in August 2016 to build the mall and garage.

“The language is in there for a bank to be part of this phase so the people are reassured the project gets done,” Suarez said at the time. “Yet Flagstone hasn’t provided the city with financial statements showing Bayraktar has the money to build it.”

At a Sept. 27 court hearing, Gonzalo Dorta, a private attorney representing the city, claimed that Flagstone’s lawyer Stearns would try to stop any efforts by the city to determine if Bayraktar could indeed self-finance the project. But Stearns scoffed at the assumption that Flagstone doesn’t have the capital to complete Island Gardens. “We wouldn’t be litigating if that was the case,” he said. “Flagstone has invested well over $100 million. The city is now trying to confiscate the property like this is Cuba or Venezuela.”

Stearns claimed Herbits was ultimately able to convince three of Miami’s elected officials to go against Flagstone due to their aspirations for higher office. Opposing the project was a way to curry favor with voters, Stearns said. At the time of the May 30 vote, then-Commissioner Suarez was in the middle of his mayoral campaign, another commissioner was contemplating running against him, and a third had just announced he was running for Congress.

“They changed the political climate in the city with regards to Flagstone during the eve of an election,” Stearns said. “[The commissioners] got on the boat despite the undisputed fact that city staff said that Flagstone was not in default. It wasn’t one of the city’s finest moments.”

Nevertheless, Flagstone won a small reprieve shortly after filing this most recent lawsuit. Miami-Dade Circuit Court Judge William Thomas granted the developer a temporary injunction allowing the company to continue operating the marina.

Even if Flagstone prevails in the February trial, the company could face years more in delays through lengthy appeals. And another lawsuit recently filed against the city by three Miami residents could also stall the project. The new complaint claims the city charter requires that because Flagstone and Miami officials altered the original agreement by carving the project into phases, the project needs to be rebid and another vote by the citizens has to take place.

Still, Stearns insists that Flagstone is going to win against the city and against the latest complaint filed by the project’s opponents.

“It is an important, valuable project for the Bayraktar family,” he said. “Granted, building it has not been as much fun for them as they thought it would be. At the end of the day, Island Gardens will get built, and it will be successful.”