When Avra Jain started redeveloping the historic Vagabond Hotel in 2012, people thought she was crazy.

When Avra Jain started redeveloping the historic Vagabond Hotel in 2012, people thought she was crazy.

With few tourist destinations nearby, the debris-ridden, mosquito-infested former motel on Biscayne Boulevard in the MiMo District was far removed from the glitzy sophistication of Brickell and South Beach.

One of the former Wall Street bond trader-turned-developer’s biggest challenges in launching her rehab projects is getting banks and lenders to believe in her vision, she said.

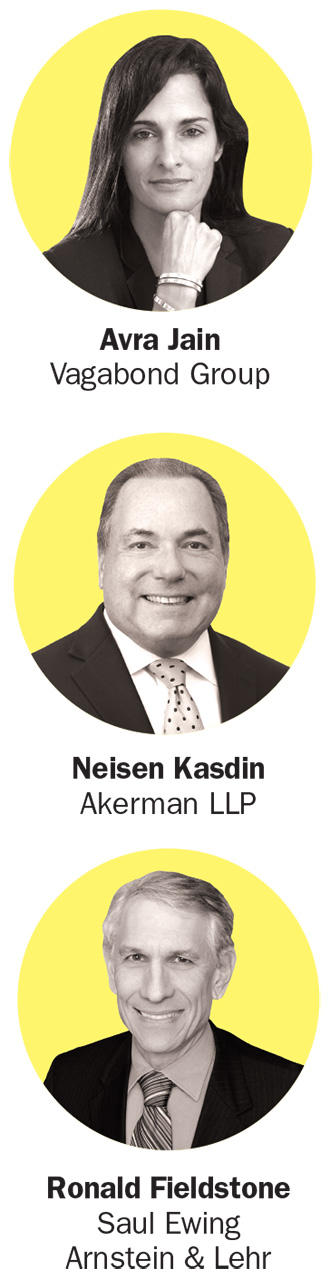

For developers like Jain, securing a loan to build or redevelop properties in distressed areas has always been a challenge. But now, things could change, she asserts. Jain, the founder of the Vagabond Group, is developing some of her projects in designated Opportunity Zones, tracts of land covered by a federal program that allows investors and developers to defer or forgo some of their capital gains taxes in exchange for putting money into projects in low-income areas.

Tucked away in the Trump administration’s 2017 tax bill, the Opportunity Zone program was crafted as a way to spur on development in low-income areas often neglected by institutional money. The once little-known provision has become perhaps the most talked about subject in the real estate world.

Jain predicts that the legislation will make it easier for developers like her to get financing.

“For lenders, it decreases the ‘walkability’ from the borrower, as investment groups will value these investments higher than traditional investments in order to protect their tax incentives and the safe harbor of capital gains,” Jain said.

Others in the industry doubt that lenders will be more apt to finance Opportunity Zone projects in distressed areas. Although the program provides big tax breaks to developers and investors, lenders won’t necessarily want to follow.

“You are not going to see lenders lend in areas just because they are in an Opportunity Zone,” said Ronald Fieldstone, a Miami-based partner with the law firm Saul Ewing Arnstein & Lehr who has worked on Opportunity Zone real estate deals in Miami.

If investors and developers hold assets in an Opportunity Zone for at least 10 years, they can forgo paying capital gains taxes on the appreciation of the Opportunity Zone asset. This could amount to huge tax savings, according to experts.

The rules, however, don’t give any incentives or tax breaks to the lenders for those projects.

“The banks aren’t really a direct beneficiary,” said Economic Innovation Group founder Steve Glickman, whose think tank Economic Innovation Group was credited with coming up with the initial plan behind the Opportunity Zone program.

There is also currently nothing in the Opportunity Zone legislation that gives banks the ability to meet their requirements under the Community Reinvestment Act, a federal law enacted in 1977 that requires banks to lend to and help the communities where they take in deposits. The CRA was designed to incentivize banks to lend in economically distressed areas where they otherwise would not, according to a study from the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University.

Glickman said banks will likely push to get a CRA provision included as part of the program.

Higher prices, fewer loans?

Many real estate investors are currently sitting on the sidelines and refraining from deploying capital until more rules come out from the U.S. Department of the Treasury and IRS on Opportunity Zones. Others, however, have already jumped the gun and started investing.

In Miami-Dade County alone, property sales in Opportunity Zone sites totaled $942 million from April through September 2018, a 25 percent increase from the same time in 2017, according to an analysis of county sales records by The Real Deal.

But all the hoopla around Opportunity Zones comes with a downside: Property values are rising too quickly, sometimes at prices higher than lenders feel comfortable with for lending.

Camilo Niño, CEO of LV Lending, a Miami-based non-bank lender, was looking into offering loans on two Opportunity Zone projects. The firm is also an equity partner on two other developments within Opportunity Zones. But the rise in land prices can make it less feasible for asset-based lenders like LV Lending to lend to these projects, Niño said.

“People are starting to pay too much for land for the development projects in Opportunity Zones,” Niño said. “If the values and premiums are too high, [Opportunity Zone sites] won’t be competitive.”

Niño also pointed out that it’s hard to evaluate the values of Opportunity Zone sites since the program is new, and it remains unclear how some of the federal rules and regulations will play out.

“I have to value with comparables, I cannot put a premium on an Opportunity Zone site,” Niño said.

Neisen Kasdin, Miami Beach’s former mayor and now managing partner of leading Florida law firm Akerman’s Miami office, sees some challenges for lenders because of how green the Opportunity Zone program is. And that’s causing some lenders to be reluctant in making certain loans.

Neisen Kasdin, Miami Beach’s former mayor and now managing partner of leading Florida law firm Akerman’s Miami office, sees some challenges for lenders because of how green the Opportunity Zone program is. And that’s causing some lenders to be reluctant in making certain loans.

“One thing that projects in O-Zones have going against them is they don’t have established real estate markets,” Kasdin said. “For your typical lender there is no established market, I don’t care how secure it is.”

The upside for lenders

Opportunity Zones do present some advantages for banks. For one, the program will allow them to help fill in funding gaps between equity and debt in Opportunity Zone projects, said Glickman, who served as a senior economic adviser in the Obama administration.

Other experts believe a major benefit of the program is the increased amount of equity and capital from developers in Opportunity Zone projects, which makes them more appealing to lenders who can help fill out the capital stack.

Last year, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin predicted that Opportunity Zones could bring in more than $100 billion in private capital. Now, developers with projects in distressed places, such as Jain, can potentially get money from a number of investors rather than being the sole backer for projects or relying more heavily on debt financing.

“It’s going to increase the amount of equity in these projects, [and] it will make the loans-to-value ratios more favorable,” said Akerman’s Kasdin. “More capital in a project gives more comfort to lenders.”

Andrej Micovic, a project finance, land development and government relations lawyer at Miami’s Bilzin Sumberg, said in addition to increased capital, the returns on Opportunity Zone projects will likely be higher because the tax benefits are so sizable.

“There is probably more room for negotiations on terms with lenders,” Micovic said. “Maybe some projects that are perceived to be higher risk would now be able to receive finance terms that will be more doable.”