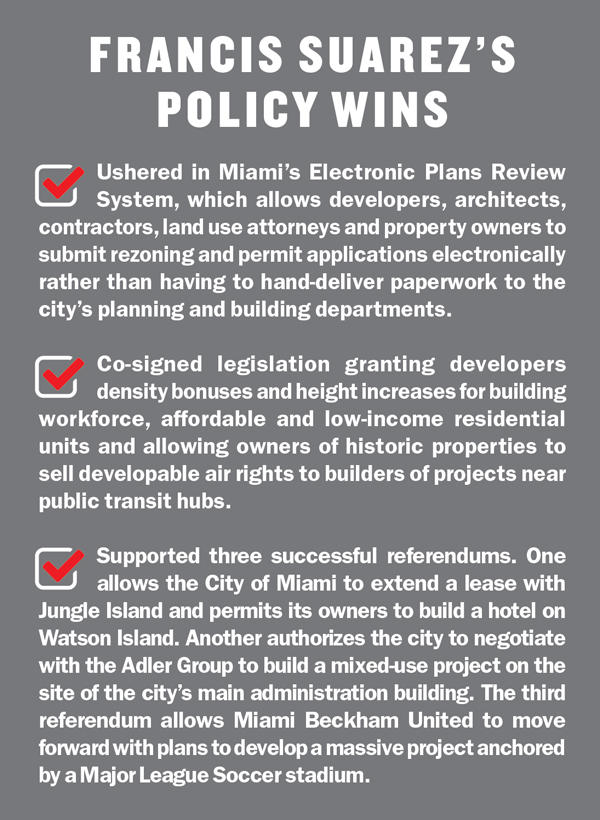

What a difference some digitizing makes. In early October, Miami’s Planning and Zoning Department finally entered the modern age. With the soft launch of Miami’s Electronic Plans Review System, developers, architects and land use lawyers no longer have to schlep over to the city’s administration building to hand-deliver site plans and requests for rezonings. In December, the digital service was further expanded to accept applications to the various permitting divisions in Miami’s Building Department.

“In the old days, you had a huge roll of plans that you had to take to file; then you would get it back with comments,” Miami land use attorney Iris Escarra told The Real Deal. “Then you would take the plans to electrical and get their comments. When you got comments from every discipline, you then had to resubmit the plans and go through each one again.”

Getting Miami’s archaic bureaucracy to join the 21st century is one of the initiatives championed by Mayor Francis Suarez during his first 12 months in office that will pay off for Miami’s real estate industry, according to Escarra and other local experts. As the first year of his term wraps up, TRD examined his work on the issues that matter to the real estate industry.

“[The real estate industry is] looking for efficiencies … I think that is why they support Francis. It is something he has talked about doing for a while,” said Marc Sarnoff, a former city commissioner and a partner with Shutts & Bowen.

Suarez has also garnered support from the development community by co-sponsoring legislation that doles out incentives allowing builders to add units and square footage to projects. For instance, the mayor backed a measure approved by the City Commission that allows developers of projects near Metrorail and Metromover stations to buy air rights from owners of historic properties in order to achieve height increases and density bonuses.

“It helps owners of historic properties make money,” Escarra said. “And it helps developers near transit build extra units.”

Another Suarez-supported measure that provides builders with double density bonuses for creating mixed-income housing has spurred new development in Miami’s Flagami neighborhood, Escarra said.

Another Suarez-supported measure that provides builders with double density bonuses for creating mixed-income housing has spurred new development in Miami’s Flagami neighborhood, Escarra said.

“There are a bunch of projects taking advantage of this program and are making entire buildings a mix of workforce, affordable and low-income housing,” she said. “There is one on Flagler Street and Southwest 37th Avenue, and another one on Southwest 15th Street and 17th Avenue. Both are apartment rental buildings that are finalizing permits now.”

The ‘strong mayor’ fail

By leading the charge to modernize the city’s plans and permitting systems and championing developer incentives, Suarez galvanized the real estate industry’s support for his ultimately failed “strong mayor” referendum, according to observers.

“There is a natural tendency in Miami’s business community to get behind our mayors, especially a guy as young and vibrant as Francis,” Sarnoff said. “I think they believe that with him, city government will get fixed.”

Had the measure passed, Suarez would have assumed full authority over the city’s administration, including the permitting departments. That means Suarez could hire and fire all employees in the Planning and Zoning Department, as well as recommend approval or denial of real estate projects to city boards and the City Commission. It’s a prospect roundly embraced by the city’s most prominent developers, brokers and land use lawyers, who raised more than half of the $1.2 million for Suarez’s referendum political action committee.

“I was very disappointed that the ‘strong mayor’ initiative did not go through,” said N.R. Investments principal Nir Shoshani, one of the few local builders who said he did not donate to the campaign but supported it.

Some of the big donors, like Terra’s David Martin, Magic City Casino owner Isadore Havenick and Coconut Grove mansion developer Douglas Cox, did not respond to requests for interviews.

Suarez’s loss on that front could weigh heavily on major development and infrastructure projects he supports. One of those projects of particular note is the plan to transform 73 acres of city-owned land currently used as a public golf course into a massive technology and entertainment mixed-use project anchored by a 28,000-seat stadium for David Beckham’s Major League Soccer franchise. Known as Miami Freedom Park, the project is another priority on Suarez’s agenda.

Voters approved the stadium site the same day the “strong mayor” referendum failed, but the Beckham group still needs to secure votes from four out of five commissioners to seal the deal. As of press time, Commissioners Manolo Reyes and Willy Gort were firm “no” votes.

Suarez critics claim that the way the mayor and the city manager rushed through the stadium ballot measure is a sign that he was not ready to assume more powers.

David Winker, a lawyer and real estate broker who lives in Miami’s Shenandoah neighborhood, said the way Suarez and Gonzalez handled negotiations with the Beckham group was not transparent and led to doubts about whether the city would be getting fair market value for the 73 acres.

“This deal did not involve consensus-building,” Winker said. “I think Francis lost a lot of faith from residents, and the ‘strong mayor’ vote shows it.”

As the cloud of the referendum’s public failure clears, Suarez will be able to focus on how to continue shaving time off the planning and permitting process and enacting other developer incentives that reward setting aside units for Miami’s middle- and low-income residents, Sarnoff said.

“Inevitably, people will still support Francis,” he said. “They see in him youth, intelligence and vigor that can change and produce a more rigorous local government that can efficiently handle permitting and things like that.”