Big real estate lenders often find themselves allaying investor concerns about a faltering market. But perhaps no one’s ever done it quite like Johnny Allison.

“The reality was [as] if Peter Pan can no longer fly, Minnie Mouse left Mickey for Goofy, … with Frankenstein piloting to take over the banking industry,” Allison, the founder and chairman of Home BancShares, said on the firm’s most recent earnings call in January. “Nevertheless, we sent Batman, Superman and Nancy Pelosi to save the day, and they built a wall around the airport and saved us all.”

Somewhere in that rant was a message: Despite the doomsdayers, Home BancShares, a lender with significant exposure to South Florida’s real estate market, is in good shape. With just $15 billion in assets, it has become one of the top 20 real estate lenders in the region, with more than $219 million in local commercial real estate loans in 2018, according to an analysis by The Real Deal.

Operating under the name Centennial Bank, its commercial real estate transactions made up more than 58 percent of the bank’s total loans in 2018. The bank hasn’t shied away from complex, ground-up projects for everyone from property and storage mogul Moishe Mana to Brooklyn-based development powerhouses Spencer Equity and Rabsky Group. Centennial’s increased activity while other lenders retreat draws natural comparisons to another Arkansas institution, Bank OZK (formerly Bank of the Ozarks), the most active condo-construction lender of this cycle.

“Home BancShares sees what the returns are at Ozarks, and they said they want to do that too,” said Jeffrey Miller, a veteran banking analyst at FocusPoint Research. “They have done it on a more granular level; it hasn’t come to the mainstream.”

But with the company continuing to acquire regional banks and Allison’s gung-ho approach to the lending business, that’s about to change.

Appetite for risk — and other banks

Like Bank OZK, Centennial is betting big well outside its home state of Arkansas, with a focus on major real estate markets like Miami and New York City.

Take Moishe Mana’s trade hub in Wynwood. Mana is looking to build a complex of over 10 million square feet with the stated goal of facilitating trade between the Americas and Asia.

“We’ve taken the initiative to create the platform for the new chapter of Miami,” Mana told the Miami Herald in late 2017. “I know it sounds very, very ambitious. It sounds almost arrogant. But somebody needs to do it. Somebody needs to start it.”

“We’ve taken the initiative to create the platform for the new chapter of Miami,” Mana told the Miami Herald in late 2017. “I know it sounds very, very ambitious. It sounds almost arrogant. But somebody needs to do it. Somebody needs to start it.”

But when Mana finally scored financing for the project — which many say is unrealistic — his lender wasn’t one of the national heavyweights. Instead, it was Centennial that coughed up a $20.1 million mortgage. So far, though, few of Mana’s projects have gotten off the ground, and in interviews with the media, Mana has been opaque about when these projects are going to be completed. Centennial did not respond to questions about when it is going to get paid back. A representative for Mana did not return comment.

Centennial also partnered with LV Lending on a $51 million construction loan to Robert Suris’ Estate Investments Group for its 306-unit Soleste Alameda apartment project in West Miami and loaned $17 million to the Hilton hotel in Pompano Beach.

Allison has always maintained that the bank operates in a disciplined manner, and that the narrative of being reckless that’s thrust upon it is an unfair one.

“We’re a very disciplined lender,” he said on the earnings call. “We don’t push a ROE [return on equity]. We don’t force loans. We don’t force deals. I don’t think anybody gives a damn.”

But according to regulators, the bank might be a bit too zealous.

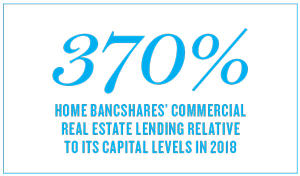

Its commercial real estate lending relative to its capital levels — a widely used barometer for risk — was 370 percent in 2018. Regulators warn against exceeding 300 percent.

Centennial also has a serious appetite for South Florida banks. In September 2017, it acquired Pompano Beach-based Stonegate Bank — one of the largest banks in the region, with $3.1 billion in assets, whose major loans included a $26 million loan to Jason Halpern’s Three Hundred Collins boutique condo project in Miami Beach. That project has recently been engulfed in litigation over allegations that Halpern’s firm, JMH Development, failed to “meet its financial obligations.” In October, a judge ordered JMH to turn over its remaining interest to its silent partner.

Centennial has also acquired a few smaller community banks in the region, including Broward Bank of Commerce and Fort Lauderdale-based Landmark Bank.

Investors are increasingly skittish about community banks’ real estate exposure, as many signs point to a slowdown in prime markets, particularly in the luxury condo sector. There’s also increasing talk of a broader economic downturn.

“Nobody wants to talk about the recession, but it’s going to happen,” said Kenneth Thomas, a Miami-based banking analyst. “A recession’s greatest impact is going to be on CRE, and the banks that don’t have the strongest underwriting [on CRE].”

Centennial’s focus in the region, said Southeast Florida Division President David Druey, “has always been long-term and smart, organic growth in the real estate arena. We recognize constantly changing market dynamics, such as the recent softening of the spec home and ultraluxury sectors, and remain nimble to seeking opportunities that properly balance our lending portfolio and meet our structure.”

The duck hunter

A short, garrulous 72-year-old with a flowing silver mane, penchant for white suits and red pocket squares that match the colors of his beloved Arkansas State University Red Wolves, Allison looks like a character straight out of “Dallas.”

He’s also got a made-for-TV personality. “Johnny is one of the very few people who has — this term is overused by people — charisma,” former Arkansas Gov. Mike Beebe told the American Banker in 2013. “It is a trite word, but he has a real magnetism.”

A former mobile home entrepreneur, Allison started Home BancShares as First State Bank, growing it to become one of the most powerful financial institutions in Arkansas. The bank went public in 2006 on the Nasdaq stock exchange under the ticker HOMB, and as of press time was trading at around $19 per share.

By all accounts and metrics, the bank has performed exceptionally well at a time when community banks are struggling to compete with the likes of Wells Fargo, Bank of America and JPMorgan Chase.

Home BancShares has been profitable for 31 straight quarters. Its net income in 2018 more than doubled year over year to $305 million. For the second straight year, it was ranked by Forbes as the country’s best bank.

That track record has been personally lucrative for Allison, who ranks as one of the highest-paid community bank CEOs in the country. His total 2018 compensation totaled $4.7 million, according to the company’s most recent proxy statement. Included in his compensation package is $7,000 that Allison uses to pay his pilot for personal trips on an airplane Allison owns.

Though Randy Sims assumed the CEO mantle in 2009, Allison continues to be a key architect of the bank’s strategy. He insists on conducting the earnings calls, in which analysts and investors can be treated to references ranging from the killing of Osama Bin Laden to stories about his friend Vince who had one too many whiskeys. In 2013, he told the American Banker he still personally vets every loan over $1 million.

“Not that I’m any genius,” he told the publication. “I just want to know who I’m doing business with. Look them in the eye.”

New York, New York

Centennial’s growth in South Florida and New York City has largely stemmed from the bank’s aggressive acquisition strategy. Since 2010 it has acquired 17 banks, according to its annual filing.

Allison previously said the bank is the largest acquirer of failed banks in the state of Florida.

“Their opportunity at home is so limited for deposits, a lot of them [community banks in Arkansas] have to go chase cash somewhere else,” said Christopher Whalen, an investment banker who runs Whalen Global Advisors.

The bank’s riskiest move, however, came in 2015, when it made its foray into what is largely regarded as the most competitive real estate market in the country: New York City.

It purchased a pool of national commercial real estate loans worth about $289 million from an affiliate of private investment firm J.C. Flowers & Co. The loans were originated by Doral Bank, the Puerto Rican bank that collapsed in 2015 amid allegations of fraud (In 2011, a top executive brought in to clean up the bank was killed in a drive-by shooting in San Juan.)

The New York office that managed those loans became known as Centennial CFG. Led by former Doral Bank executives, the division is headed by Christopher Poulton and operates almost as a separate entity within Centennial, lending to large real estate projects throughout the country.

One of its deals is a $65 million construction loan for Rabsky Group and Spencer Equity’s eight-building Broadway Triangle residential and retail development in South Williamsburg. The project will have more than 1,100 units of housing, with nearly 300 affordable units, and 65,000 square feet of retail space.

The CFG unit operates quite like the Real Estate Specialties Group, a Dallas-based entity within Bank OZK that makes big construction loans while the rest of Bank OZK acts more like a regular community bank.

“Loans derived from the New York loan production office are traditionally determined by their larger size and scope of the deal,” said Centennial’s Druey. “Loans originated by the South Florida region specifically focus on community banking relationships.”

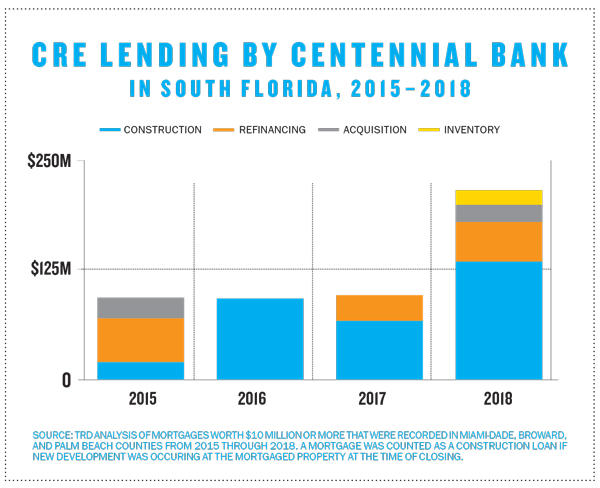

Since the CFG unit was established, the bank has made a big push into construction lending. In South Florida, its construction lending grew from just $20 million in 2015 to more than $137 million in 2018. Overall, the bank increased its total commercial real estate lending in South Florida to $219 million from $96 million during that same time.

The New York office was even responsible for the bank’s largest construction loan in South Florida, $80 million in 2016 to Property Markets Group’s 32-story, 464-unit X Miami apartment project in downtown Miami. PMG paid off the loan in September, after it scored a $106 million financing package from Pacific Western Bank and restructured Square Mile Capital’s preferred-equity position in the deal.

Damn the dissenters

Allison himself has noted the skepticism about its New York office. “We opened an operation in New York,” he said during the January earnings call. “Regulators, analysts and just about everyone continues to question that. Even today, our New York office simply continues year after year to make more profit than any other region.”

The concerns stem from both the type of loans made and the bank’s national ambitions.

Unlike Bank OZK, who makes much larger condo-construction loans often upwards of $100 million, many of Centennial’s commercial real estate loans are between $20 million and $80 million and go to a variety of asset classes including multifamily, condos, and commercial projects. For example, in 2017, Centennial provided $88 million to strip club owner Robert Gans to refinance his 14-building portfolio in New York City. Late last year, Centennial provided a non-recourse loan to the Jay Group for a mixed-use project in Harlem, according to the Commercial Observer. Non-recourse loans are generally viewed as riskier since a lender cannot go after the collateral of the borrower if there is a default. And the bank has begun ramping up in Los Angeles and Dallas.

“When you see loan production offices in areas outside of banks core competencies and headquarters, those tend to be pretty risky, those tend to be the ones that result in a bank going down,” said Bill Cormany, a federal bank regulator with the FDIC, speaking generally and not specifically about Centennial.

“You can’t be a master of all markets,” said Thomas. “You got a bank that is so spread out — that becomes a red flag.”

Allison, however, says the bank’s loans are all backed by significant equity. And in 2018, Centennial’s New York office reported no write offs. On the earnings call, he made his opinion about those with opinions on his bank clear.

“Thank you all, all our supporters, who’ve been with us for many years,” he said. “And to hell with the naysayers.”