After 40 years of working for his father, Tibor Hollo’s oldest son, Wayne, readily admits, “There is only one Mr. Hollo.”

Known in South Florida as a visionary, Tibor has led Florida East Coast Realty for more than six decades, forging new ground by developing Miami’s Omni and Venetia areas as well as Brickell’s first high-rise, the Rivergate Plaza tower. By all accounts, he remains the company’s chief decision–maker.

One of the biggest hurdles that family real estate businesses encounter is preparing the next generation to take the reins and navigating the transition in leadership, particularly when a strong personality looms behind the company’s success. Florida East Coast Realty, founded by the now 88-year-old Tibor, is facing just this challenge. And he is not alone.

More than a dozen South Florida builders, developers, property managers and sales agents have welcomed their offspring into their businesses, to provide new vision and skills. While some of the country’s biggest real estate players (like Cousins Development of Atlanta and Tishman Speyer of New York) have entered the Florida market and left, these local family firms have powered through, changing strategies when necessary to compete. A few have even become among the industry’s most profitable firms.

In Miami, well-known condo developer Jorge Perez has welcomed his son Jon-Paul-Perez into his firm. Miami Beach developers Russell Galbut and Bruce Menin are benefitting from the involvement of a son, Jared Galbut, and a nephew, Keith Menin, in the hospitality side of the business. In Fort Lauderdale, Terry Stiles at Stiles Corp. recently announced his plans, after running a construction firm for 44 years, to hand over CEO duties to his son Ken by mid-2017. In a bit of a twist, Pedro and David Martin founded Terra Group together in 2001 and have proved themselves a dynamic father-son duo in South Florida real estate. Four generations of the Murphy family have been involved in running a construction management company that today ranks among Florida’s largest general contractors. In 2013, Ana-Marie Codina Barlick succeeded her father, Armando Codina, as CEO at Codina Partners, and Jessica Goldman Srebnick has followed in the footsteps of her late father Tony Goldman, a force behind the revival of South Beach and Soho.

Running a business with a family in charge, especially for three or four generations, comes with its own set of challenges amid the rewards.

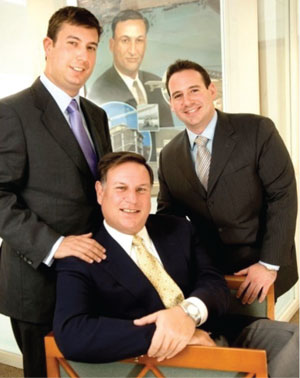

The Hollo family-owned firm is now embarking on what might be its most ambitious project to date: the 83-story Panorama Tower in Brickell, scheduled for completion in 2018. Tibor has set the vision for what the $800-million mixed-use complex will look like, who it will attract and how the components fit together. “These big projects are conceived by my father,” Wayne said. “He knows what he wants to do.” As plans become more concrete, the Hollo family gathers almost daily for progress updates — at the office, over dinner, at Tibor’s home.

With three generations working together, things go more smoothly if each family member is assigned a specific role in the company, said Wayne, who’s charged with administrative issues and finance. His brother, Jerome, handles legal work, and Wayne’s son, Austin, takes care of leasing, marketing and insurance matters. Tibor still sits at the helm, setting direction and negotiating all the many pieces that must come together for a project of this size.

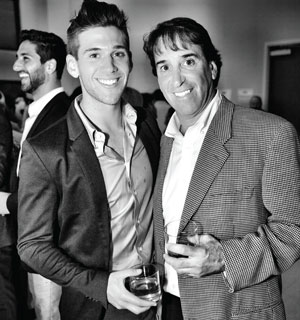

The responsibility of taking the company into the future is something 29-year-old Austin thinks about; he said he uses the family meetings to learn the entire company’s workings, while paying close attention to his grandfather’s rules for doing business: Don’t go over 50 percent leverage, have a team member on a project site at all times, challenge yourself professionally and take risks. “I come in every day with my ears and eyes open,” Austin said.

Succession is just one concern. Family real estate businesses also face the challenge of sustaining an older generation’s influence while adapting to change in the marketplace.

The Rok family has grappled with just this scenario. Cuba-born Natan Rok arrived in Miami in 1964 and opened a retail business on historic Flagler Street. He began buying properties in the central business district, growing his firm to become one of the largest commercial landlords in downtown Miami.

While Natan built rapport with his 300 tenants and closed most of his deals with a handshake, today his son Sergio finds it difficult to do business in the same informal way as his dad did. Natan died in 2004 and Sergio now runs the Miami company, a property management and real estate investment firm.

“Reputation is something that still means a lot to us,” Sergio said. “I take pride in selecting who I do business with and some business is still done with a handshake, but nowadays things are different.” Sergio said he does due diligence, prepares documents and cautiously selects his business partners before making a financial commitment. “The recession really taught people that not everyone would do the right thing during unfortunate times,” he said.

Sergio said his father would want Rok Enterprises to maintain an impeccable reputation. “In our 40 years of doing business, there is not a single time we have missed a payment or asked for a reduction,” he claimed. “We have paid everything we have gotten a loan for and that’s important to my company. I’m trying to instill that in my nephews and son.”

For the Roks, the leadership change from father to son was a smooth one. “Most of the time I was working with dad, I would always be in his office,” Sergio said. “If he had a meeting with tenants, it would not be strange to see me around and part of those meetings, so tenants were already used to dealing with me.” Sergio now employs the same mentoring technique and includes his son in meetings. “He is listening, learning and trying to understand our complicated projects,” Sergio said.

Today at the office of Rok Enterprises, Sergio can look to the left or the right and see family. His two nephews and a brother-in-law have roles, as does his son, Jared. When there’s a difference of opinion, majority rules, although Sergio admitted, “Ultimately I’m responsible so I need to be O.K. with it.” He recognizes that the dynamics of his current company — with its diverse holdings and partnerships — are far more complex than the one his father oversaw.

“If you are in business with family and you get along, it’s great, but it’s not for everyone,” Sergio observed. “You have to leave your egos outside and do what’s best for the company. It works for us.”

When a parent doubles as a boss, there can be an added pressure on a child to succeed. Jeffrey Soffer experienced that when he went to work for his father, Donald Soffer, the developer behind the Turnberry community, the city of Aventura and the Aventura Mall. Rather than finishing a college degree, Jeffrey tried to learn everything he could about business and real estate from his father, who allowed him to exert independence — and make mistakes, Jeffrey said.

Jeffrey worried about messing up something that his father had spent years building; he also feared not being involved on the forefront of new real estate development. That meant he ignored comments when people told him he was crazy for expanding outside Florida, buying the Fontainebleau Miami Beach or pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into new projects. Over the years, Jeffrey drew on his father’s example of innovation. “They told my father he was crazy for building Aventura, but he built it anyway,” he said.

Taking risks has come with some costs, though, Jeffrey has found: In 2009 he filed for bankruptcy protection of Fountainebleau Las Vegas, once pegged as a roughly $3 billion resort. Today the litigation and millions in losses related to the Las Vegas experiment are largely in the past for him. (Billionaire Carl Icahn bought the entity but hasn’t restarted construction.)

Jeffrey has learned to come to terms with his blunders, he said. “Everybody in business as a real estate developer on big scale is going to make mistakes. I know that now and obviously I learned from them and moved on.”

Amid the recent economic recovery, the Soffer Family’s Turnberry Associates is moving forward with Jeffrey and his sister Jackie continuing to follow the vision of their father Donald: “We are leaders in what we do, not followers,” Jeffrey said. Their 1,504-room Fontainebleau Miami Beach, reopened in 2008 after a $1-billion renovation, ranks among the largest resorts in South Florida. A father of three, Jeffrey (who married Elle Macpherson in 2013) said he will encourage his children to enter the family real estate business — with a caveat: “Of course, I’ll be around to make sure they don’t screw up.”

For some families, the mechanics of doing business together can take some figuring out. Those interviewed said it can be difficult not to slip back into the parent–child dynamic of years ago, resulting in friction when a member of the younger generation wants to assert leadership.

Representing the third generation in his family real estate business, Jimmy Tate confronted this issue after joining his father’s company in the 1980s. Though his brother was content to build residential projects alongside his dad, taking orders from a parent after graduating college wasn’t what Jimmy wanted.

Alicia Cervera Sr., center, encourages a spirit of teamwork in her family-led firm. Projects are launched with a celebratory meal together.

Jimmy had his own ideas and wanted to act on them. So he cut a deal with his dad to venture off on his own, tackling more entrepreneurial real estate projects with a high risk-reward potential. “I felt it would be easier to take guidance from him if I were working for myself,” said Jimmy.

In 1986, 22-year-old Jimmy bought 12 partially developed lots in Plantation at a distressed property sale with a loan from his dad. He designed and built homes on them and sold them at a profit, paying back his father the loan, plus 10 percent. That’s how he launched Tate Development, the precursor to his current firm, Tate Capital, which he operates with his brother Kenny, who oversees the underwriting and economics of deals while Jimmy is the frontline dealmaker.

Over the last 30 years, Jimmy and Kenny have developed numerous residential and commercial projects in Florida and other states. They also bought a significant amount of distressed commercial real estate debt over the last six years in partnership with the Rok family and condo developer Jorge Perez.

The Tate brothers have earned a reputation — apart from their father’s — as savvy real estate developers and investors. And now the next generation is showing interest; Kenny has a daughter who recently joined the firm.

Today Stanley Tate, 87, works from the same North Miami office as his sons and manages the real estate investments he holds after years of building in South Florida (and taking over a real estate firm founded by his father-in-law, Morton Greenwood).

Referring to his father, Jimmy said, “I love his advice, but I don’t want to work for him.” He added, “We invest with each other. We advise each other. It’s a great family relationship. Every family business is different and each has to figure out how to make it work.”

Even when the upside has been proved, leaders of a family business can find it difficult to embrace a third generation. The potential for jealousy, hard feelings and disagreement looms. To avoid conflicts, the Cerveras try to put traditional family roles aside in the office and make business decisions as a team at Cervera Real Estate in Miami.

A spirit of teamwork is encouraged at a family dinner held at the beginning of every new project. This longstanding tradition brings good luck to the family real estate sales business and its newest project, asserted Alicia Cervera Sr. in an interview. At the kickoff of every condominium project for which she is hired to sell units, the entire family dines at Café Abbraci in Coral Gables, toasting to sales success with a bottle of Veuve Clicquot.

The outside world may see Alicia Sr. as the matriarch, but her daughters, Veronica Cervera Goeseke and Alicia Cervera Lamadrid, are equal partners and she treats them as such, she said. (Alicia Sr.’s niece Sildy and daughter-in-law Jennifer Cervera also work for the company.)

Alicia Sr. encourages her daughters to be the faces of the company at events and together they make the decisions about expenditures. So now two generations of Cerveras are serving as women leaders in the business, even as they usher in yet more female sales professionals from the next generation.

Alicia Sr.’s granddaughters Alicia and Alexandra (along with grandson Nickel) bring a global perspective after traveling to places like China, Brazil and Mexico to lure international buyers to Miami. “They head to the airport like I would to a phone booth,” said Alicia Sr. “I have become O.K. with that because I can see they have the same dedication to the business.”

For families in real estate who have roots in other countries, bringing the business to South Florida can be a risky move. Jose Luis Melo, who had a real estate company in Argentina, took a gamble on land in Miami’s Edgewater area in 2001 and brought his two sons, Carlos and Martin, along with him on the bet.

The area near downtown Miami, with rundown buildings and vacant lots, was hardly fancy. Yet the father saw opportunity in its Biscayne Bay views and highway access, and Carlos and Martin trusted their father’s instincts. More than a decade later, their development company Melo Group of Miami has completed six rental and condo towers. The family controls a large stake in Edgewater and has ventured into Miami River, Brickell and Allapattah.

Showing trust for a family member doesn’t mean ignoring proper checks and balances but rather considering his or her strengths and experience, Martin said. Carlos has a background in architecture while Martin is knowledgeable in accounting and finance. “We often have different opinions,” Martin said. “If we don’t think someone is right, we argue. But we have to trust that as a team we are going to agree on the best solution.”

While challenges exist, the advantages of family businesses are there, too: There’s an implicit understanding that everyone is working to create a legacy.

Matt Adler sits at a desk in the same office of the Adler Group as his father, Michael. He is close enough to ask for advice but far enough away to not have every move supervised. It has taken a few years for Matt to find his comfort zone in the family business. With a background in finance, he didn’t want to assume an identity similar to that of his developer and property manager father. “Professionally my dad and I are different personalities, with different mindsets and different risk thresholds,” Matt said.

Seeing opportunity in real estate investment, Matt orchestrated a joint venture in 2012 between Miami’s Adler Group, founded 50 years ago by his grandfather Samuel, and Kawa Capital, an independent asset management firm. The new entity would go on to raise and manage a fund to buy properties in growth markets. “Spearheading the investment business was the right thing for me,” Matt said.

Now CEO of Adler Kawa, Matt aims to be a trailblazer like his grandfather and dad but in investment rather than development. “Within the fund space, I’m trying to keep the family legacy of identifying new opportunities that are overlooked by the herd,” he said.

“It’s not always easy blending family and business relationships,” Matt said. “Even though my father is a supporter, and helped me facilitate becoming an entrepreneur, my new role is a manifestation of some of those challenges of working too close together and finding the right middle ground.”

At Shoma Group, Masoud Shojaee has welcomed his two daughters into his Miami real estate development business; both Lilibet and Anelise have master’s degrees in the field. He imagines that in the future, he will serve as an adviser to them much like his father, a developer in Iran, had been for him.

For now, he’s trying to walk a line between showing them what to do and gauging when they’re ready to assume more responsibility. In September he found himself quite surprised after meeting with Lilibet to discuss a residential project: “She had better ideas,” he said. A company can start to slide if leaders lose touch with the market but can keep its edge by bringing in the next generation with fresh thinking, Shojaee said. “My daughters understand the value of advice,” he said. “And so do I.”