Moishe Mana sits down at the head of a conference table in his Wynwood office and immediately slips off his Louis Vuitton shoes, leaving his bare feet to just brush the tile floor.

“It is crazy, you know. Like I was in Colombia now, I was walking barefoot on the beach for three days,” said Mana, who has a habit of smiling while he talks. “I need to take the shoes off everywhere I go.”

Mana is a spiritual person. He’s not just developing a mixed-use project, he is “building an ecosystem.” His plan is not just a vision, but rather a “philosophy.” More important than financial returns, his ambitious new facilities will bring value to a society at a time when he believes we are threatened every day by what he considers “dangerous policies from President Trump.”

His goal is to make Miami a thriving startup and tech hub like his hometown of Tel Aviv, a place at the forefront of art, culture and innovation. But after five years of amassing older downtown properties, Mana’s master plan has yet to take off. Now he’s seeking a $400 million to $500 million capital raise for his companies, from family offices and high-net-worth individuals.

Part of downtown is arguably in worse condition than when Mana started buying years ago, as his buildings are showing signs of disrepair and many remain vacant.

“I love the fact that someone has plans because the area has terrific potential,” said Crescent Heights CEO Russell Galbut, who is co-developing an Airbnb-branded condo tower nearby in downtown. “We already own some property in the area and know that with more developers present, more can happen.”

As those banking on this project continue to hope for a groundbreaking, some wonder if his project will ever come to fruition.

Developer David Arditi said he’s been following Mana’s plans closely, and that the information surrounding them “isn’t perfect and the timing of the project seems rather uncertain.”

Mana’s vision is unclear even to savvy Miami real estate developers who have studied the area.

“I don’t know if it’s any clear plan. I’m confused,” said Harvey Hernandez, who developed the condo tower Centro in the Flagler area. “It’s unfortunate because he owns so much real estate downtown. Executing that plan would create so much value downtown with what everyone is trying to create.”

To be sure, Mana has had remarkable success in nearly every aspect of his career. He fought off the Mafia to build a moving and storage empire in New York City. He helped revitalize the city’s Meatpacking District, and he created a burgeoning art community in Jersey City by converting warehouses into over 2 million square feet of studio, exhibit and archive space.

To be sure, Mana has had remarkable success in nearly every aspect of his career. He fought off the Mafia to build a moving and storage empire in New York City. He helped revitalize the city’s Meatpacking District, and he created a burgeoning art community in Jersey City by converting warehouses into over 2 million square feet of studio, exhibit and archive space.

But if Mana is unable to get the capital and start delivering soon, he may have missed his chance to develop, considering that the real estate cycle is coming to an end. More so, the challenges in downtown Miami, including major permitting issues, appear to be too great even for Mana to overcome on his timeline.

Downtown distress

Mana likes to talk — especially about things other than real estate. That’s because to the 63-year-old, the way that developers have been speaking is entirely backwards.

“For me, the building is not important. It’s not the content of the building but content within the buildings, and that’s what’s going to make the neighborhood sustainable,” said Mana.

His downtown vision involves creating co-working and co-living components, a hotel, food hall and public gathering spaces. In theory, this “ecosystem” will provide young professionals with almost anything they would need.

So far, Mana has amassed nearly $375 million worth of properties downtown totaling over 1.3 million square feet of buildings on about half a million square feet of land. He is by far the area’s largest private landowner, according to an analysis by The Real Deal.

The historic section of downtown is faced with a growing homeless population and a lack of public bathrooms, resulting in the human feces often found on the sidewalks.

“Downtown has forever been an area of the city that watched other neighborhoods develop but was never redeveloped itself,” architect Bernard Zyscovich, who is designing Mana’s projects, said.

Mana feels bad for business owners who are suffering, but he argues that he’s not to blame and that the problems existed before he showed up. “Actually, I’m the savior here,” he said.

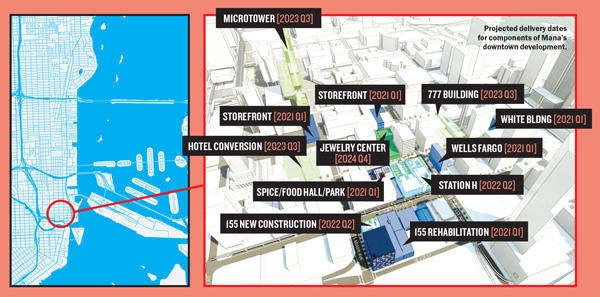

After years of starts and stops, lags in communication with the public and increased pressure to actually break ground on something, the Mana Group finally unveiled a construction timeline for downtown Miami in late October 2019. At a community meeting, maps and renderings designed by Zyscovich Architects highlighted 11 buildings between Southeast First Street and North Miami Avenue that would be delivered between the first quarter of 2021 and the fourth quarter of 2024.

Mana’s first project will be renovating the 166,365-square-foot, circa-1980 office building at 155 South Miami Avenue, which will be home to Miami International University of Art and Design as well as a startup hub.

Mana’s team has also been working behind the scenes to get the $22.5 million renovation of the sidewalks, parking spaces and streetscapes of Flagler Street back on track. The city, Miami-Dade County and the Downtown Development Authority are funding the new version of the project. The City Commission approved the last piece of funding to redo the streetscape in July.

Not leaving anything to chance, Mana paid for the redesign after the first version fell apart and the city fired its contractor, FH Paschen. Only one block was completed, and construction is expected to restart after the Super Bowl is hosted in Miami next year.

Mana’s biggest hurdle for the project will likely be the problem that plagues many other developers: the building and permitting process, which is known to take forever in the city of Miami due in part to insufficient city staff.

Gary Ressler, a downtown Miami landlord, said a bar seeking to open in his building has been waiting on the city for 18 months. A Bank of America ATM has taken more than a year and a half to get a permit, he added.

“[Mana] has plans, so far aspirational, but he has plans,” Ressler said. “Will the city get out of the way and make it happen?”

City Commissioner Ken Russell said the city has done everything it can for Mana to pull the trigger, in part by speeding up the process with a new online permitting system. He also said the city has invested in initiatives to help with homelessness, graffiti and general upkeep.

Mana said he’s beginning to grow impatient because he’s aware that it will take a long time to develop downtown. He calls Miami “one of the most difficult cities that I encounter as far as approval permits.”

“I’m getting antsy myself,” he said.

Missed opportunities

On top of the issues with permitting, Mana has missed out on opportunities to bring in commercial tenants.

He says he wants the right type of tenants that go along with his so-called ecosystem. But it’s hard to deny that the real estate cycle in Miami is at the tail end. The high-end residential market — generally the first to show signs of distress in the real estate market — is languishing.

At the end of the third quarter of 2019, there was almost an eight-year oversupply of condos in downtown Miami priced at over $1 million, according to Analytics Miami, a Miami-based brokerage and consulting firm. This represents the second-worst condo resale market in Miami, after the Edgewater neighborhood — just north of downtown.

“This massive buildup past $500K is a sign that the neighborhood did not live up to promise and hype,” said Ana Bozovic, the founder of Analytics Miami.

The few other developers near the major thoroughfare of Flagler Street have been able to bring in new tenants while many of Mana’s buildings remain empty and neglected. He also bypassed large commercial tenants like WeWork, which leased the entire Security Building on Northeast First Avenue in late 2017 and remains there today.

Mana shows no regrets, saying, “Only time will tell if I was right or wrong.”

Who is Moishe Mana?

This isn’t the first time Mana has had doubters. The developer was raised in a rough neighborhood of Tel Aviv to parents who emigrated from Iraq. After dropping out of law school in Tel Aviv, he moved to the United States in 1983 in pursuit of a better life.

He began by washing dishes and occasionally sleeping on park benches in New York City before saving up enough money to buy a moving van. He started Moishe’s Moving Logistics with a goal of breaking up the heavily unionized moving business through lower prices and cheaper labor.

Moishe’s Moving rose to become one of the largest moving and storage companies in the tri-state area, reportedly upsetting John Gotti and the Gambino crime family, who had power over the unions.

In an interview with the Israeli newspaper Haaertz, Mana said Gotti once called him.

“He said, ‘You’re stepping on our toes, taking our livelihood.’ I replied, ‘I live at 201 West 21st. If you want to kill me, come over now and we’ll get it over with,’” Mana told the outlet.

Gotti backed away, but Mana’s real prize was the collection of storage facilities and warehouses he started amassing along the way. In 1998, his real estate portfolio totaled more than 1.5 million square feet in the New York metro area. Soon thereafter, he began to redevelop space in the neglected Meatpacking District.

Mana found a niche in converting old warehouses into art communities and studios. He was able to do this successfully in Jersey City with Mana Contemporary, and he was one of the first to capitalize on this in Wynwood, building his massive Mana Wynwood complex, which he opened in 2010.

“We want to make it interesting and affordable,” Mana said in 2015. “The magic of South Beach is over, and the movement is now toward downtown and the Brickell areas.”

It wasn’t until 2014 that he was introduced to downtown Miami and saw its potential. To Mana, a contemporary-art lover, it was an opportunity to take the city’s most historic properties and breathe new life into them.

“It was 12 o’clock at night. A friend of mine took me to show me a building somewhere in downtown, and I’m driving and my head was spinning. I said, ‘What is going on here? Why is it so quiet? Why is it so locked down?’” said Mana. “It was something I felt in the air for whatever reason. Maybe it reminded me of the old Tel Aviv neighborhood.”

Shai Ben-Ami, a real estate investor and restaurateur, introduced Mana to his colleague Mika Mattingly, then a commercial agent with Sterling Equity Realty. (Mattingly would go on to broker nearly all of Mana’s roughly 50 purchases in downtown, fending off other agents who were hungry to score a piece of Mana’s buying frenzy.)

“It took him 20 minutes with us in downtown to realize he would spend two, three hundred million dollars,” said Ben-Ami on a walking tour of the neighborhood’s bars.

Mattingly, now at Colliers International, remembers vividly Mana’s local shopping spree. “He would buy buildings without even looking at them. It was a crazy time,” she said.

Time crunch

Mana has spent a fortune acquiring properties in downtown Miami, and he claims that up until this point he has provided all of the equity for these projects along with debt financing from banks and nonbank lenders.

For the downtown properties where Mana is a registered agent, he has secured at least $137 million in loans along the way, according to an analysis of property records and loan documents by The Real Deal.

Mana admits that getting investors to believe in his vision has been difficult. Because of that, he is working with smaller lenders such as Conway, Arkansas-based Centennial Bank to finance some of his projects. The bank provided $51 million in loans to two of Mana’s downtown properties and Mana Wynwood. He also relied on the Puerto Rico-based Doral Bank, which collapsed in 2015 amid allegations of fraud and whose Florida branches were taken over by Centennial. (In 2011, a top executive brought in to clean up the bank was killed in a drive-by shooting in San Juan).

Mana has also gotten loans from JP Morgan, Bank Leumi and Miami developer Sergio Rok.

Another one of Mana’s lenders is Ladder Capital Finance, which provided Mana with a $7 million loan from in 2015 that was paid off in 2016, records show. The nonbank lender gained a reputation as a lender of last resort and was used by President Trump during his development days when other banks turned him away, according to Crain’s New York.

The bigger issue for Mana, though, is the capital raise, which will cover all of his projects, not just his downtown project.

Mana’s team insists that it would be difficult to get a large institutional partner like BlackRock to invest in the project, since they believe these firms will be too constraining on what Mana is trying to do. The question now becomes whether Mana will meet his capital raise, given how vast his plan is and the problems plaguing some of his projects.

In the meantime, Mana said he will continue with bank financing.

“It became very complicated because it’s not a simple business plan. It’s a million arms, you know, a million businesses within them, and how do you put it together? How do you educate the investor?” Mana asked.

99 problems and downtown is just one

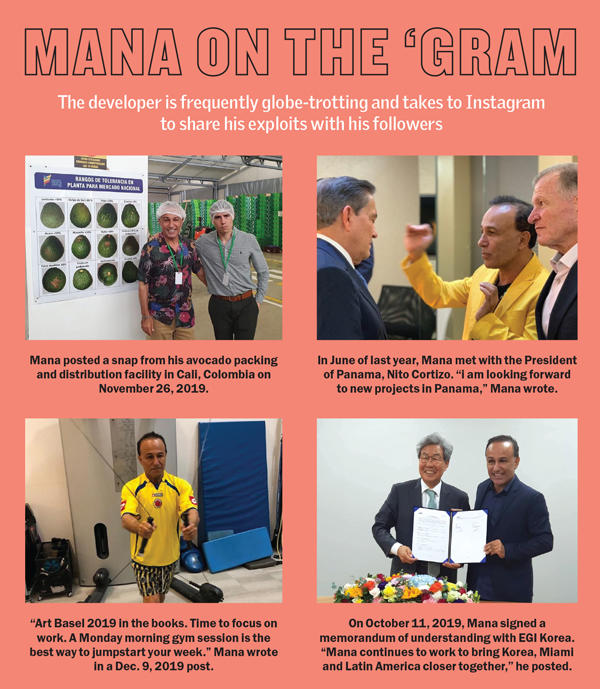

Mana’s Instagram portrays him as a renaissance man, akin to Elon Musk, who is spearheading dozens of groundbreaking ventures at the forefront of innovation. Untethered by a partner or children, he’s frequently on the go, traveling the world over. One day Mana’s in Saudi Arabia in front of a helicopter, claiming he’s helping the Saudis with arts and entertainment. The next, he’s meeting with the president of Panama to connect the country with Asian investment. On some days, he even checks in on his avocado packing and distribution facility in Cali, Colombia.

The question for potential investors is, how big a priority is the downtown Miami project for Mana?

In Miami, at least, his company’s bigger long-term challenge might be in Wynwood, where Mana sought to break ground on a massive 10 million-square-foot trade center connecting China and Asia with Latin America, North America and the Caribbean.

That project has been put on hold, Mana’s people say.

“The issue we’ve had in Wynwood is we’ve focused so heavily on finding an institutional partner from China and then the impact on the trade war and the setback that happened,” said Teddy Ward, Mana’s chief of staff. “I don’t think anyone could have anticipated how dramatically the tide turned on that.”

Mana’s mind is wandering with ideas on how he wants to change the world. But one thing he makes clear is that he is not going to flip his downtown properties.

“Try me,” said Mana, seemingly agitated by the question. “I’ve been approached many times. I don’t even want to discuss price, because it’s something that’s part of a legacy. It’s not for sale. It’s a commitment. I want to see it through.”