Matis Cohen is a frustrated developer.

Since 2010, he has been investing millions of dollars buying low-rise apartments and commercial properties in North Beach, which he describes as a distressed realm largely ignored by real estate developers in spite of its close proximity to white, sandy beaches. “To have a blighted area in Miami Beach is just unfathomable,” Cohen said. As for why he chose to invest in North Beach at all, Cohen answered: “It’s a great opportunity for effecting change.”

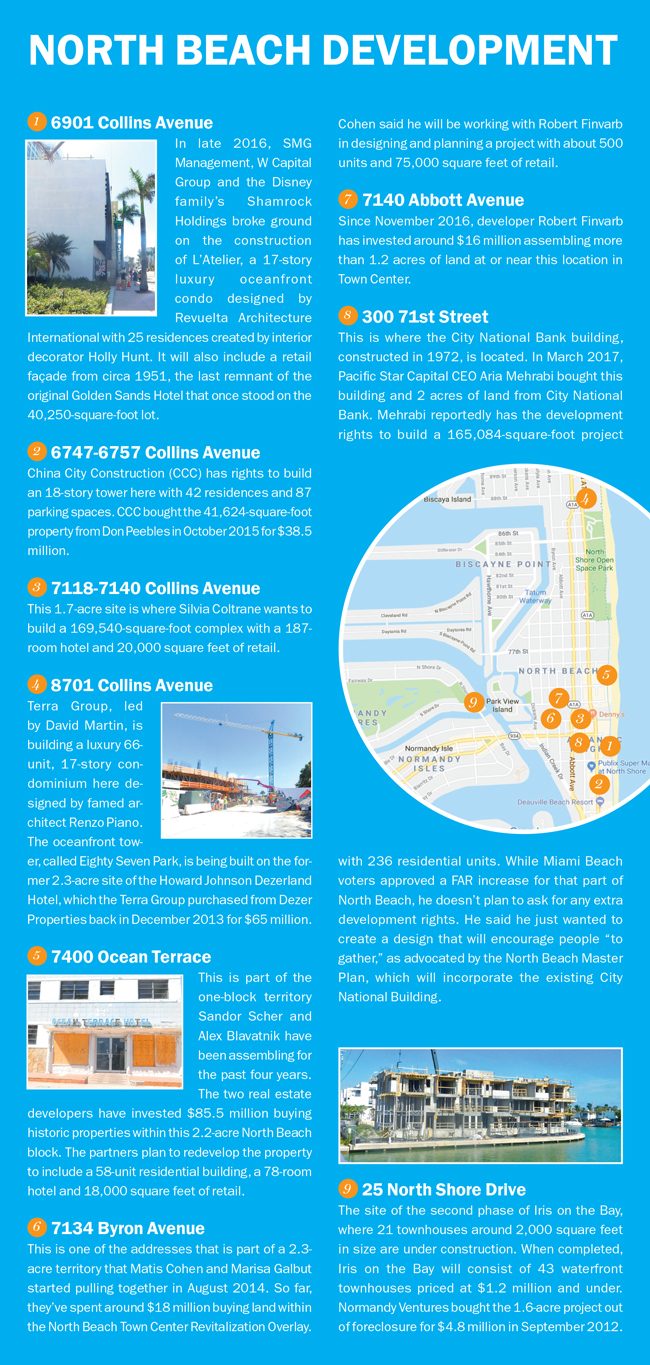

But Cohen had assumed change was just around the corner. On Nov. 6 of last year, Miami Beach voters approved a referendum increasing the floor area ratio (FAR) of a 10-block region within North Beach called Town Center, which is bordered by Indian Creek Drive, Dickens Avenue, 72nd Street, Collins Avenue and 69th Street. FAR is used to calculate future density. At its current density, which reflects the old regulations, the FAR on Town Center — containing a couple of gas stations, an apartment building, retail plazas, some aging office buildings and vacant lots — is between 1.25 and 2.5. The referendum jacks that up to 3.5 throughout the Town Center, allowing builders, in some cases, to more than double the density now allowed. In order for the new rules to take effect, the Miami Beach City Commission will need to conduct a final vote, which is scheduled for May 16.

Cohen said that the density increase, when it goes through, should be a catalyst for further economic development elsewhere in North Beach. It would also add direct value to some of Cohen’s properties. Cohen and Marisa Galbut, the daughter of longtime Miami Beach developer Russell Galbut, own 2.2 acres of land within Town Center, at 71st Street on Byron and Carlyle avenues.

Unfortunately for Cohen, the FAR hike still hasn’t been approved by the city. Nor are there any design guidelines regulating height, setbacks and parking regulations. Without the FAR increase and design guidelines, property values remain stagnant, and, Cohen said, he can’t build. It isn’t clear if design regulations will be passed before the summer recess in August.

This worries Cohen. In spite of the referendum’s passage with 58.6 percent of the vote, he argued that Miami Beach officials and residents have “an addiction to restrictions.” As a result, Cohen believes that Miami Beach officials are “dragging their feet” during a time when market conditions could become more averse to real estate development. “It’s very easy to stop something in Miami Beach,” he said.

This worries Cohen. In spite of the referendum’s passage with 58.6 percent of the vote, he argued that Miami Beach officials and residents have “an addiction to restrictions.” As a result, Cohen believes that Miami Beach officials are “dragging their feet” during a time when market conditions could become more averse to real estate development. “It’s very easy to stop something in Miami Beach,” he said.

Real estate developer Robert Finvarb is more optimistic. Miami Beach residents, Finvarb believes, recognize that larger buildings are needed to jump-start North Beach’s stagnant economy. “The voters have spoken; now it’s just getting through the bureaucratic process,” said Finvarb, who owns property on 71st Street and Abbott Avenue.

Still, Finvarb — who wants to develop a mixed-use project designed by Arquitectonica with Cohen and Galbut consisting of 500 residential units and 75,000 square feet of retail — does understand the frustration from North Beach property owners who, he said, are interested in building and not selling.

“This is not Wynwood. You’re not going to see a lot of trading of land here,” Finvarb said. “You’re going to see a neighborhood created.”

Compared to South Beach’s Lincoln Road, where retail leases for $300 a square foot, or even parts of Biscayne Boulevard where retail rents hover around $60 a square foot, North Beach is a bargain, with retail rates ranging from $20 to $50 a square foot.

It isn’t too expensive to live there, either. While it’s hard to find a studio in South Beach under $1,100 a month, in North Beach, monthly residential rents range from as low as $900 for a studio to as high as $1,800 for a three-bedroom, Cohen said. “We are on par with Allapattah,” said Cohen, referring to the industrial, working-class Miami neighborhood where the median monthly rental rate for a one-bedroom was just a little less than $1,200 in March of this year, according to Zumper.

Because North Beach is a mixed bag of affluent and working-class neighborhoods, condo and single-family home prices range widely from under $150,000 to over $7.5 million, experts said. However, the three major projects that are currently being built in North Beach — 25 North Shore Drive, L’Atelier and 8701 Collins Avenue — cater specifically to affluent buyers (see map on page 32).

Already raring to build within Town Center is Silvia Coltrane, who owns part of a 1.7-acre site at 7118 Collins Avenue. Back in January 2017, Coltrane obtained the blessing of the Miami Beach Design Review Board for her 129,337-square-foot project that includes a 10-story, 179-room hotel, 23,754 square feet of retail, a 141-space parking garage and an existing Denny’s. But now, thanks to the referendum and the FAR increase that she’s certain will follow, Coltrane said she intends to submit new plans for a 169,540-square-foot project with eight more hotel rooms and an additional floor. “The [FAR increase] allows me to bring a better hotel, with more hotel rooms and better amenities,” Coltrane said.

Sandor Scher is also eager to start building his ambitious project within Ocean Terrace, an area in North Beach near the beach that includes the 27-story St. Tropez condominium, boarded-up historic hotels, restaurants and a parking lot. It’s here, at approximately 75th Street and Collins Avenue, that Scher and his partner Alex Blavatnik plan to mix the old with the new by redeveloping 12 hotel properties and retail buildings constructed in the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s. Plans for the final product include a 16-story, 58-unit residential building, a 78-room hotel and 18,000 square feet of retail.

Scher said it took him and Blavatnik four years to put together the assemblage and get their design plans through the city bureaucracy. Now Scher is worried that economic conditions will shift against development in general.

“The financial markets have to still cooperate,” said Scher, who finally received the blessing for his revised Ocean Terrace plans from Miami Beach’s Historic Preservation Board this past January. “So, you know, how much room is left on the runway? We don’t know. Interest rates are starting to creep up a little bit. There are things that are creating risk for people who want to develop.”

Scher had previously sought and failed to get a FAR hike in 2015. Voters approved an increase for Town Center last year after two bitter enemies in North Beach, real estate developers and preservationists, worked out a bargain: in exchange for developers’ support of the creation of two new historic districts in North Beach, the preservationists would support a FAR increase for Town Center.

“Right now, the historic preservation of major areas, 271 buildings, has already gone through,” said Daniel Ciraldo, executive director of the Miami Design Preservation League. “The Tatum Waterway, which is another 100 buildings, is still in the process … That will happen around May.”

Some preservationists want the city to hold off implementation of the FAR increase until all 371 buildings are protected, Ciraldo admitted. There was also debate amongst city commissioners about whether or not they needed to figure out the design guidelines at the same time the 3.5 FAR would be implemented. After four months of discussion, Commissioner John Elizabeth Alemán said she persuaded her colleagues to move forward with the FAR increase first, fearing that the debate could be used by upzoning opponents as a means to forever delay the process. “The will of the voters must be implemented right away,” she said.

Part of that will is implementing the North Beach Master Plan that was crafted by Dover, Kohl & Partners in October 2016, which called for the creation of a pedestrian-friendly, dense environment that can be packed with rentals that are not just for people who earn six figures or more, but also for low- and medium-income households.

Seth Feuer, a Realtor with Compass and co-chair of the Miami Beach Chamber of Commerce’s Real Estate Council, said such mixed-income projects could enable more people who work in Miami Beach to live there.

“About 33,000 people come over the causeway every day to come to work. They can’t afford to live here,” Feuer said.

And such mixed-use projects could come about faster, Cohen asserts, if Miami Beach’s city planners tried to work with developers instead of trying to “dictate” to them.

The city is in the process of negotiating with Aria Mehrabi, a Santa Monica-based developer. Mehrabi wants to swap five of his lots on 71st Street between Abbott and Byron avenues with the city of Miami Beach in exchange for five city-owned properties along 71st Street, according to Susan Askew, co-chair of the chamber’s Real Estate Council. The land swap proposal will be discussed by the city’s Planning Board on April 17.

Miami Beach Commissioner Kristen Rosen Gonzalez insisted she won’t stand in the way of that progress. Still, Gonzalez thinks that Miami Beach residents will change their minds once the first Town Center mixed-use projects are completed.

“I’m not a huge fan of density increases on a barrier island, and the reason why is there’s no transit solutions,” Gonzalez said. New retail and apartments, Gonzalez stressed, bring with them additional traffic. “The only reason we have any mobility is because we controlled the density,” she said.