Tour the Panorama Tower overlooking Biscayne Bay, with its “porte cochere,” poolside cafe, wine tasting rooms, pet spa and home theaters, and you might think that you’re sampling Miami’s latest glitzy condominium offering.

Rising nearly 900 feet, Florida East Coast Realty’s project is the tallest building in the state. But unlike many of the other towers that dot Brickell, the Hollo family’s development firm decided to build rentals. It even tapped Fortune Development Sales, a top condo sales and marketing firm, for the leasing assignment, and targeted trendy and hip Miamians — “Brickellistas.”

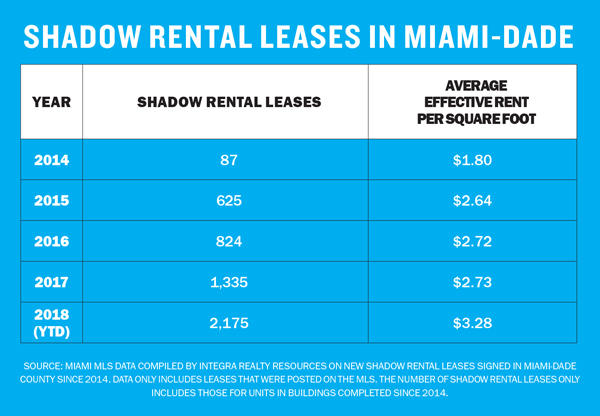

Banking on the city’s population growth, its hunger for big corporate tenants and homeownership’s diminishing prominence in the American Dream, FECR and other developers have bet that Miami, like New York, will become a city of renters. They’re building top-shelf product and wooing the prosperous with a playbook they’ve adapted from their condo-building counterparts. But their approach could directly threaten condo investors, who are increasingly looking to generate income by putting their units on the rental market. In Miami-Dade County, nearly 2,200 leases have been signed on the so-called “shadow rental market” so far this year, data from Integra Realty Resources show, up from fewer than 100 shadow rentals in 2014.

In the face of increased competition from rental developers with newer product, a central tenet of buying a unit for investment — renting it out — is being challenged. And while large rental landlords are able to adjust prices in the event of oversupply or a downturn, individual condo owners, dealing with a myriad of fees and taxes, have less wiggle room on pricing, meaning they could be shut out.

“Owning a condo and renting it,” said Manny de Zárraga, the Miami-based co-head of HFF’s National Investment Advisory Group, “is not a great business.”

Apartment therapy

So far, developers’ big bet on luxury multifamily projects seems to be paying off. Panorama is leasing out at rents that range from $2,500 a month for a one-bedroom to over $6,700 for a three-bedroom. More than half its 821 units are leased out, according to Jerome Hollo, president of FECR.

Comparable properties have also done well. Recently built Class A apartments in Miami-Dade saw net operating income grow 74 percent between 2015 and 2017, according to The Real Deal’s analysis of county figures.

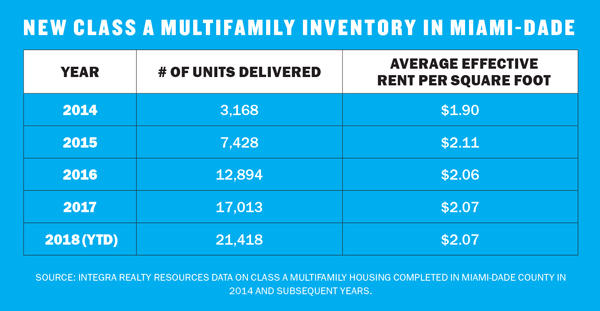

That the sector is posting such numbers despite a large supply bump says a lot. Since 2014, more than 20,000 Class A apartment units have come to market in Miami, according to a TRD analysis of data from Integra, which creates residential reports for the Miami Downtown Development Authority. Yet asking rents have only climbed.

“When we went through the last real estate crash, the sales prices of residences went down,” said Jack McCabe, CEO of McCabe Research & Consulting in Deerfield Beach. “But rentals never did.”

All that supply, however, is expected to eventually push rents down. That’s especially true for Miami because, unlike other cities in the Southeast such as Charlotte or Atlanta, it still lacks giant corporations with their well-heeled workers — RIP Amazon HQ2 — to anchor its rental market. Couple that with foreign and out-of-state condo investors who are now dumping their units on the rental market, and some experts sense that something’s got to give.

Calixto García-Vélez, who oversees FirstBank Florida, said he is barely doing any new construction lending for Class A Miami apartment buildings. On top of the new product coming to the market, the banker said, condo rentals will flood the renter pool, which will temporarily drive down rents. The market will be fine in the long term, he thinks, but as rents drop, so will the bank’s lending activity to this asset class.

“Condos that were for sale are now being put in rental pools,” García-Vélez added.

New data provides a look at just how pronounced this trend is. So far this year, 2,175 shadow rental leases — contracts between a condo owner and tenant — have been signed in Miami-Dade, up 60 percent year over year, according to Integra. The number of condos on the shadow market today would then represent about a fifth of the total units delivered this cycle — nearly 11,200, according to an analysis by ISG Miami of the condo development hotbeds in Miami-Dade east of I-95, Fort Lauderdale, Hollywood and Hallandale Beach.

This could be bad news for condo owners because there are a lot more apartments to compete with these days, said Anthony Graziano, a principal at Integra. In Greater Downtown Miami alone, of the more than 24,000 multifamily units in the pipeline this cycle, roughly 11,000 units have been delivered or are under construction, he said.

And while major rental landlords generally have a fair bit of flexibility built into their pricing and can adjust rents in the face of a spike in supply or other challenges, condo owners — burdened with property taxes, homeowners’ association fees and special assessments — can’t be as nimble, putting them at risk of losing the price-conscious renter.

Condos are clearly more expensive. A conventional apartment is renting out for $2.07 a foot, while a condo rental is leasing at $3.28 a foot, according to MLS and CoStar data compiled by Integra.

Condos are clearly more expensive. A conventional apartment is renting out for $2.07 a foot, while a condo rental is leasing at $3.28 a foot, according to MLS and CoStar data compiled by Integra.

For a luxury condo market that reportedly already has a years-long oversupply of inventory, this could produce a mass selloff, some skeptics say, or — at the very least — a steep drop in prices.

“It’s a day of reckoning for [condo] owners,” said Peter Zalewski, a principal with the Miami real estate consultancy Condo Vultures and an investor in the bulk-condo market.

Deal flow

Depending on pricing, demand and ability to build, investors and developers will often toggle between the multifamily and condo asset classes.

While some bankers like FirstBank Florida’s García-Vélez have become more skeptical about funding new Class A-rental projects, developers have found themselves with plenty of options ever since the Federal Reserve relaxed rules on commercial lending this year. Apartments generally cost less to build than condos, allowing for potentially healthier profit margins, said Brett Forman, CEO of Trez Forman Capital Group, a commercial mortgage lender.

“What people fail to realize is that the supply that is being delivered is catching up with demand,” said Peter Mekras of Aztec Group, a real estate investment and merchant banking firm. Mekras believes that much of the forthcoming product will compensate for the post-crisis slowdown in supply, which stemmed from developers’ inability to get financing.

“What people fail to realize is that the supply that is being delivered is catching up with demand,” said Peter Mekras of Aztec Group, a real estate investment and merchant banking firm. Mekras believes that much of the forthcoming product will compensate for the post-crisis slowdown in supply, which stemmed from developers’ inability to get financing.

But Jim Costello of Real Capital Analytics feels the Federal Reserve’s move came at the wrong time.

“Money may be coming in on the debt side,” Costello said, “but if the tax burden is so high on developers and it’s hard to find the labor, you can’t build a building with debt alone.”

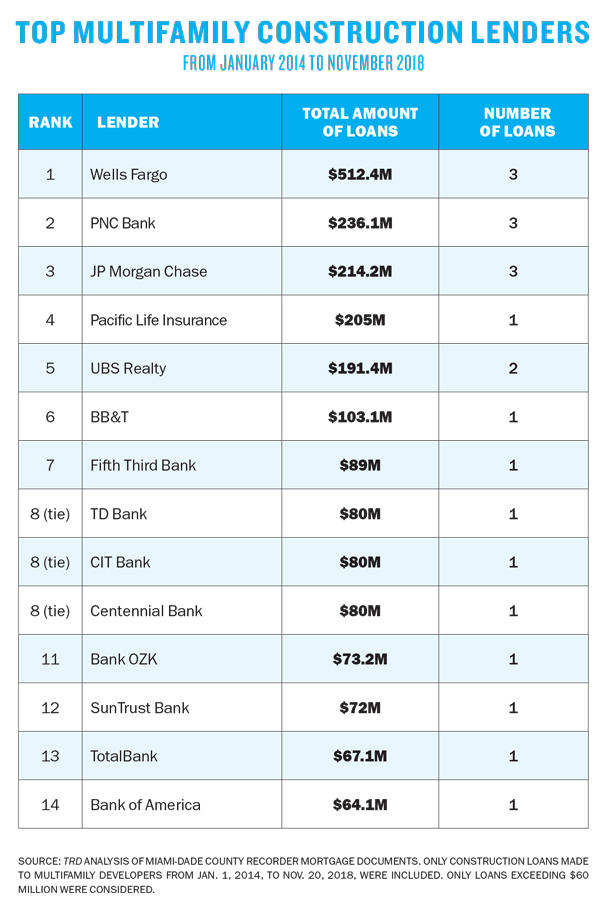

Lenders on such deals tend to be large banks or insurance firms. In Miami-Dade, Wells Fargo ranked as the top multifamily lender this cycle, with over $500 million in deals since 2014, according to a TRD analysis of large loans.

On the condo side, things are quite different. It took Two Roads Development over a year to land a $138 million construction loan from JPMorgan for Elysee, a 57-story tower it’s building in Miami’s Edgewater neighborhood. Many condo developers beginning construction now are largely self-funding their projects, as is the case with Missoni Baia, an Edgewater project being built by Vlad Doronin’s OKO Group and Cain International, and Okan Group’s Okan Tower, a hotel and condo project planned for Miami’s Arts & Entertainment District. Others have looked to Bank OZK, an Arkansas-based bank that has become the Miami metropolitan area’s most aggressive condo lender, with more than $1.2 billion in construction loans from 2013 through 2017, according to the company’s annual reports. This represented over a quarter of the dollar volume of all condo construction loans made in the area during that time.

Gables Columbus Center is among the crop of rental buildings competing directly with the shadow market.

And while the luxury condo sales market is in a funk, Class A South Florida multifamily properties are still fetching top dollar in the investment-sales market. In July, Gables Residential sold a rental complex called Gables Aventura to an asset management arm of Deutsche Bank for $149 million, or $372,500 per unit. And Related Group hopes that Icon Las Olas, its luxury rental tower in downtown Fort Lauderdale, will fetch at least $500,000 a unit, or $136 million.

That may be because many of the bigger investors aren’t necessarily sprinting after fat returns. Institutional players, such as Mill Creek Residential or Greystar Real Estate Partners, tend to make decade-plus bets and aren’t as impacted by short-term fluctuations in rent.

“They will be patient,” said HFF’s de Zárraga.

A condo by any other name …

In 2013, Miami was experiencing a post-crisis development boom. Luxury condos were launching left and right, especially in Brickell, a corner of Miami that has become a U.S. hub for Latin American financial services companies. Top developers such as Ugo Colombo, Related Group and Swire Properties set their sights on the area for their trophy condo projects. By the end of 2016, Brickell had 17 condo projects with over 5,500 units in the pipeline, according to an ISG report. Many of these units were being sold to foreign investors, some of whom then sought to rent them out on the shadow market.

With condo developers like Jorge Pérez and Jeff Soffer rising to aristocratic status in a city that reveres builders, apartment developers wanted in.

Players such as FECR, ZOM Living and Property Markets Group believed that Miami would become a national economic hub that could command high rents. They sought to create amenity-rich product and corresponding services that would cater to this future market.

Gables Columbus Center, a 200-unit apartment building that was completed in downtown Coral Gables this year, offers a resort-style pool deck, 24/7 concierge, electric car charging station, business lounge and gym. Micah Conn, development director with Gables Residential, said the project, which is about 40 percent leased, is now competing with the shadow condo market.

Gables Columbus Center, a 200-unit apartment building that was completed in downtown Coral Gables this year, offers a resort-style pool deck, 24/7 concierge, electric car charging station, business lounge and gym. Micah Conn, development director with Gables Residential, said the project, which is about 40 percent leased, is now competing with the shadow condo market.

“We have a professional staff trained at managing and leasing,” he said. “In Miami, there’s a very big investor profile. Getting your toilet fixed or your refrigerator repaired — these kinds of things might take weeks if your owner is out of the country.”

Alex Miranda of One Sotheby’s International Realty has been working and living in the Midtown Miami apartment complex since Joe Cayre’s Midtown Equities, the original developer, completed the first residential building there in 2007. Midtown 6, 7 and 8 (all separate projects) are underway and will add competing rental product to a market with a large condo supply. Consider, for example, that Related Group recently completed the four-tower Paraiso District in nearby Edgewater, bringing about 1,400 new condos to the area.

Inventory is “getting a little bit out of control,” Miranda said, adding that “it’s a lot easier to live as a renter in a rental building.”

The last time a condo building is updated is typically when the developer completes it. Once homeowners’ associations take over, “the first thing they cut is amenities” to keep costs low, Conn added.

“The age of the product gives us the advantage,” he said.

One-night stands

Where condo owners could have a leg up over apartments is in the short-term rental market. The rise of platforms like Airbnb, HomeAway and VRBO has led some investors to ditch traditional 12-month leases and focus on lucrative quickie deals.

Orlando-based ZOM completed Solitair Brickell this summer.

Some developers are emphasizing this opportunity. Aria Development Group and AQARAT are building YotelPad, a hotel and 208-unit condo building in downtown Miami with zero rental restrictions. Buyers there are free to rent their units out themselves, on websites like Airbnb or through the Yotel program. (If they do use the building’s management system, owners would have to commit to a set period of time.)

“It was definitely an intentional differentiating factor,” said David Arditi, a principal at Aria. “It’s something buyers find appealing.”

Sarah Elles Boggs, who works in condo sales at Douglas Elliman, said that end-user buyers are now dominant in the market, and they value the ability to move in quickly after closing. As a result, condos being used as traditional rentals have become trickier to sell.

“I’ve noticed a distinct increase in days on market if it’s a rental and it’s selling to an end user,” Boggs said.

Which is where short-term rentals could come in. At Canvas, a 513-unit condo set to begin closings in January, the market demanded the short-term rental option “from day one,” said Ron Gottesman, a principal at the developer, NR Investments.

NR is allowing furnished units to be rented for a minimum of 30 days at a time. Gottesman said that his main concern with allowing short-term rentals was that Canvas is one of a few dozen condo buildings in Miami to have Fannie Mae approval, and short-term rental activity could affect buyers’ ability to get home loans.

And now that the development is 90 percent sold, Gottesman is focusing on attracting end users, not investors.

“Buyers have their own thoughts about how short-term rentals are going to work,” he said. “They can make a lot of money. [But] I don’t think the buyers understand what it means; it’s intensive management,” he continued, adding that “when the end user is really buying, this is a healthy market.”