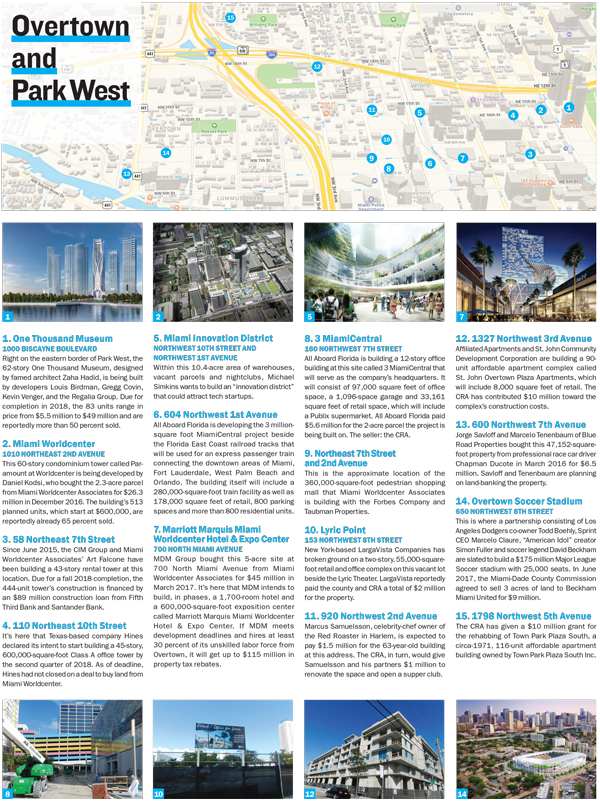

There’s an aerial map of the city of Miami on the desk of Cornelius “Neil” Shiver. His job is to promote economic development in a 600-acre swath of real estate in Overtown and Park West that’s outlined in red on the map. Between those red lines, a local real estate investor wants to build a massive “innovation district,” a soccer star promises to develop a sports stadium, a 3 million-square-foot train station is under construction, pricey condo towers are going up, a cultural and entertainment district is taking shape, and three affordable housing projects were recently completed, with a fourth on the way.

“Clearly, we have location,” Shiver said while pointing at Miami’s hot real estate spots on the map. Since December 2016, he has been the executive director of the Southeast Overtown/Park West Community Redevelopment Agency (referred to as a CRA). “We have Wynwood to our north. And, of course, we have Biscayne Bay towers to our east … Even if there wasn’t a CRA, I truly believe that economic forces would cause certain development to come over here.”

Two neighborhoods separated by railroad tracks are lumped together between the red lines on Shiver’s map. On the west side of the tracks is most of Overtown, an impoverished neighborhood that’s one of the oldest African-American communities in the city. On the east side of the tracks is Park West, a section of downtown that fell into hard times in the 1960s and ’70s but is now seeing rampant development.

As projects like Miami Worldcenter and the MiamiCentral project are attracting more interest in the area, experts say the price of square footage in both Park West and Overtown is outpacing the residential and commercial rents that can be drawn there, causing some investors to make the decision to wait until the next development cycle begins to pursue new projects in the area.

Fabio Faerman, president of Fortune International Realty’s commercial division, said there was a dramatic land price increase in Overtown two years ago, when pricing went from $80 to $150 a square foot. Park West has seen big increases, too. In March 2017, MDM Group bought a 5-acre site from Miami Worldcenter Associates for $207 a square foot. Farther east, along Biscayne Boulevard, Park West land parcels trade anywhere from $700 to $1,000 a square foot, according to Nitin Motwani of Miami Worldcenter Associates, which is developing the 12 million-square-foot village of high-rises and commercial space on 36 acres of Park West.

Faerman said the pricing jump has made things “very scary” for prospective private developers wishing to build, given that the economy of Overtown still does not allow landlords to charge even median county rents.

Retail rental rates in Overtown average around $20 per square foot, Faerman said. In the rest of the county, it’s $38 per square foot, according to a Colliers International Q3 2017 report. Park West retail rents range between $30 and $40 a square foot, Jeremy Larkin, co-chairman of the commercial real estate firm NAI Miami, said. Residential rents are lower in Overtown than elsewhere in the city. The median rent for a one-bedroom is $950 in Overtown and $1,750 in the city of Miami overall, according to a December Zumper report. However, most current Overtown residents can’t afford to pay more than $800 a month, according to Faerman.

Some of Faerman’s clients are adopting a wait-and-see philosophy, although land prices aren’t the only cause of their caution. The broker worked on a $6.7 million deal involving a 47,152-square-foot parcel between the Miami River and the site of the soccer stadium proposed by a group led by David Beckham. The buyer, Blue Road Properties, is land-banking the river property, waiting to develop it when plans for the stadium are clearer, although Faerman said the owner is open to using the parcel as a water taxi site.

The Overtown area presents other deal breakers for developers looking to do larger projects. Louis Birdman, an architect and developer involved in One Thousand Museum, has suspended his plans to build a seven-story condo garage called Auto House at 375 Northwest 7th Street.

Birdman, who may try to sell the 17,000-square foot site, thinks Overtown would be “ripe for development” if the neighborhood’s zoning were less restrictive. “What the area needs is some increase in density and increase in height so that there can be more mixed-use projects,” said Birdman, who, with partners, bought the Overtown site for $2 million in August 2016.

Most of Overtown is zoned T5 or T6-8, where buildings can be built up to five or 12 stories, respectively. In contrast, Park West is zoned T6-60 or T6-80, where unlimited height is permitted with zoning bonuses. The policy governing these two areas is directed by the five members of the Miami City Commission, one of whom is the chair of the Southeast Overtown/Park West CRA.

The local CRA is looking to continue the flow of development — and hopefully affordable housing and jobs — coming into the area, even if there’s a cooldown in interest from developers in the short term. The CRA has already offered millions of dollars in tax rebates to encourage massive development in Park West on the east side of the tracks, and, according to policy, employment on the west side of the tracks in Overtown.

Miami Worldcenter is poised to receive up to $108 million in rebates by 2030 under development agreements with the CRA in exchange for agreeing that it’ll hire at least a third of its workforce from Overtown at predetermined minimum salaries.

MDM Hotel Group will get $115 million by 2042 in rebates in a separate CRA development agreement when it builds a 1,700-room Marriott Marquis convention hotel with 600,000 square feet of exhibition space at the Worldcenter. The agreement also includes a commitment to hire Overtown workers at specified wages.

The CRA has also pledged to funnel $17.5 million in property taxes collected from All Aboard Florida’s future 3 million-square-foot MiamiCentral mixed-use project to pay for a Tri-Rail commuter train stop.

But now that Park West is filled with construction activity, Shiver said he wants to leverage those Park West property taxes not already earmarked for rebates to entice developers and entrepreneurs to build affordable housing and businesses in Overtown, especially grocery stores benefiting the predominately poor residents. “We can offer incentives to invite developers to come in and do socially conscious development,” Shiver said.

Straight cash is a huge part of those incentives. The CRA routinely hands out grants to small businesses from its $17 million budget. Then there’s the $60 million affordable housing grant that the CRA issued in 2014. That grant helped pay for the development or rehabbing of more than 500 affordable units.

Motwani, of Miami Worldcenter Associates — a company that has been investing in the Park West area since the early 2000s — said the fates of Park West and Overtown are inextricably linked. After all, both places were ignored by real estate developers until recently.

“I think the entire area has been a hole in the doughnut for growth,” said Motwani, who is on the board of directors for the Miami’s Downtown Development Authority. “As Park West and Overtown continue to develop … both sides will benefit from each other’s success.”

Despite recent reticence, some of the biggest investors already in the area are still looking to further the evolution of both neighborhoods. Developers of the massive Miami Innovation District plan in Park West are partnering with Shiver to develop the Historic Overtown Folklife Village — a cultural center in Overtown — while plans for their high-tech office center are underway.

Michael Simkins, the developer behind the Miami Innovation District, said that to date he has invested $25 million buying 20 properties and renovating buildings in Overtown. Many of these parcels are located in the area where the city has long looked to create a cultural and entertainment district, leading to the partnership between Simkins and the CRA to make the Folklife Village a reality, Shiver said.

Likely to come soon: a supper club owned by Marcus Samuelsson, the celebrity chef who runs the popular Harlem restaurant Red Rooster.

Simkins said his plans for the Folklife Village include “bringing in different restaurants and even a nightlife jazz club.” He added that he’s going to try and work with future tenants to be somewhat flexible in determining rents.

Simkins’ presence in both neighborhoods is hard to ignore. Most of the land in Park West is controlled by a “small group” of property owners, including him, he observed.

The fi rst 30 of the Paramount Worldcenter’s 60 stories were erected by early December. The

building will be completed by the beginning of 2019, project representatives said.

“Miami Worldcenter [Associates], us and Brightline own 90 percent of the land, so there’s really nothing available in that area [to buy], I would say,” he said.

Simkins and his partners spent $100 million assembling a 10.4-acre fiefdom in Park West, which includes a strip joint called E11even, the Club Space nightclub and several warehouses and vacant parcels. It’s here that Simkins aims to construct the Miami Innovation District, consisting of several mixed-use buildings intended to attract technology companies like Amazon as well as startups. The exact form this district will take is still being worked out, but it could include up to 7 million square feet of office space, plus retail and micro apartment units. If built, the district could be a huge boon to the area.

However, when it comes to Overtown, Shiver from the CRA said he isn’t interested in merely helping “land speculators” sell their property to high-rise developers who care little about the fate of the neighborhood’s current residents.

“If I ever fly over Overtown one day and I can’t distinguish Overtown from Downtown, we have failed this black community,” Shiver said.

Overtown was created during the segregated Jim Crow era as a designated place for African-Americans to live in the city of Miami following its incorporation in 1896. Colored Town, as Overtown was initially called, became a central location for blacks throughout South Florida to live, do business and enjoy recreation. The neighborhood thrived for decades. Its entertainment district, called Little Broadway, welcomed celebrity performers in the mid-20th century like Cab Calloway, Nat King Cole, Josephine Baker, Billie Holiday and Aretha Franklin.

But in the 1950s and 1960s, under what Miami’s white business leaders cheered as urban renewal and “slum clearing,” huge chunks of Overtown were demolished to make way for I-95, I-395 and the 836 expressway. Housing for at least 10,000 people and Overtown’s Central Business District were erased, and the neighborhood fell into a dismal decline. As recently as 2013, Overtown’s median household income was $15,287 a year, according to a report from the University of Miami.

Miami merged the southeast section of Overtown with a blighted section of Downtown Miami dubbed “Park West” into a CRA in 1982, allowing officials to direct property tax dollars collected in that area toward initiatives that would eliminate blight. Apart from the development of a couple of condo towers and the 1988 city-financed development of a $56 million basketball arena for the Miami Heat (which was later abandoned for the $216 million waterfront American Airlines Arena), development was still minimal.

Motwani said a huge factor that enabled Miami Worldcenter to move forward was the construction of a $1 billion PortMiami tunnel funded by the state, county and city. Prior to the tunnel’s construction, trucks traveling to the PortMiami flooded Park West’s streets. “Back when we first started, 30 trucks per hour would drive by on the way to the port,” he remembered.

And Miami Worldcenter was what attracted Simkins to Park West and Overtown. He believes Overtown’s adverse reputation is what’s keeping many private builders away.

“I think the real estate community has been shying away from Overtown because they see it as a dangerous, crime-ridden, drug-selling type of neighborhood,” he said. “That’s been the biggest impediment. And I don’t find that to be the case. I feel safe when I’m there. I think that’s a false perception of the area.”

But Faerman of Fortune said Overtown is still reeling from the time when Miami leaders divided the neighborhood up with highways five decades ago. He pointed out that Overtown has been cited by the Miami Herald as ground zero for Miami’s growing opioid epidemic.

Because the current development cycle in Miami-Dade is winding down, and it now costs the same to build in Overtown as it does elsewhere in Miami, Faerman advises against rushing in to build in Overtown.

“If you’re going to be in this location,” he said, “you’ll want to wait until the next development cycle.”