For more than a decade, local betting outfits and the Seminole Tribe of Florida have engaged in a cold war to undermine one another’s ability to expand gaming laws in the Sunshine State. Usually the clandestine battles are waged in Tallahassee during the annual legislative session, where both sides deploy armies of lobbyists to twist the arms of legislators. Now both sides are enlisting voters to join the fight, which has proven controversial within Miami’s development community.

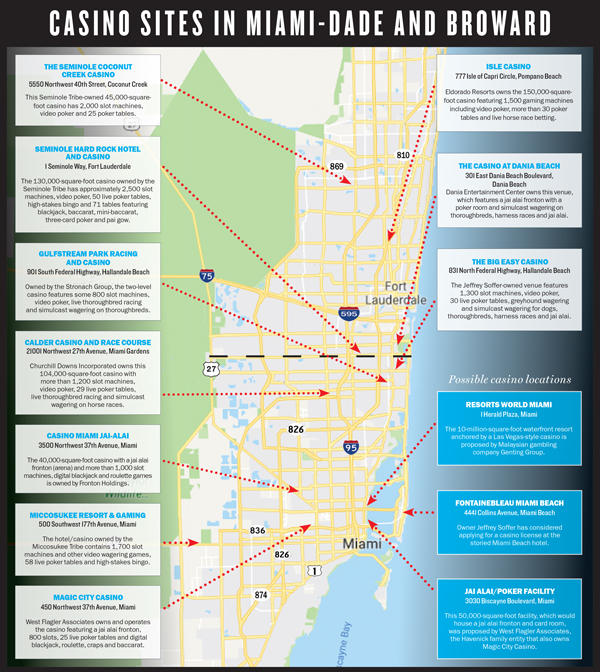

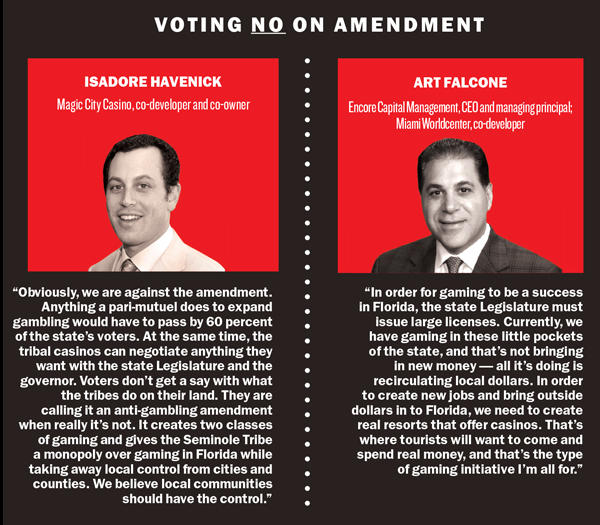

Florida’s Nov. 6 ballot has a constitutional amendment that would require that any future gambling facility not located on tribal land — whether it’s a card room or a slot machine palace — be approved by all Florida voters. That means a developer like Jeffrey Soffer, who is entertaining the possibility of obtaining a casino license for his signature property, the Fontainebleau Miami Beach, would have to launch a statewide campaign and obtain more than 60 percent approval at the ballot box. Soffer, who through a spokesperson declined requests for an interview, would also need to seek voter permission should he decide to expand the Mardi Gras Casino and Race Track, which he purchased in April for $12.5 million, renaming the property the Big Easy Casino.

The ballot measure does not apply to pari-mutuel wagering — betting pools in which those who bet on competitors finishing in the first three places share the total amount bet — and casino gambling on Native American tribal lands established through state-tribe compacts. For obvious reasons, the Seminole Tribe — which is building a $1.5 billion guitar-shaped tower at its Hard Rock Hotel & Casino site on its reservation in Hollywood — supports the ballot measure, sinking roughly $11.7 million into the anti-casino political action committee (PAC) Voters in Charge.

The gambling amendment has also created an unlikely tag team, with Disney joining the Seminoles in bankrolling the PAC. The family-entertainment conglomerate, which doesn’t even allow gambling on its cruise ships, has contributed $14.6 million to Voters in Charge. Combined, the Seminole Tribe and Disney account for nearly 99 percent of the $27 million raised to convince voters to punch yes.

For critics, the gambling amendment specifically takes power away from local jurisdictions in Miami-Dade and Broward that may want to approve new casinos. In 2004, Florida passed an initiative that granted voters in Miami-Dade and Broward the authority to allow slot machines at pari-mutuel facilities that existed and were licensed by the state since at least 2002.

Meanwhile, the Seminole Tribe and Gov. Rick Scott formed a 20-year compact in 2015 that allows the tribe, which has about 90,000 acres across six reservations in the state, to offer craps and roulette, as well as exclusive rights to operate blackjack games.

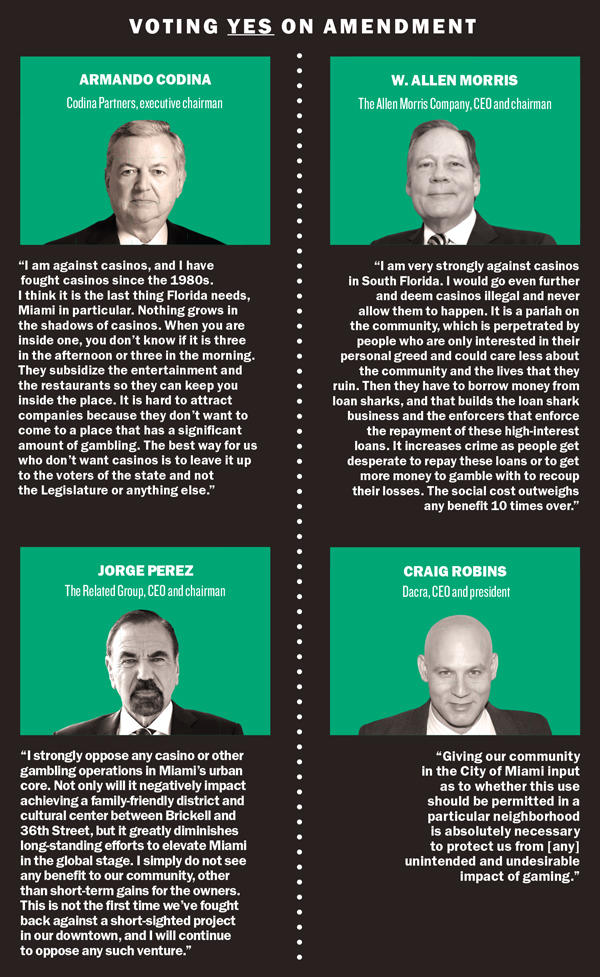

Still, the prospect of full-blown casinos coming to town is a touchy subject in Miami’s development community. In recent months, prominent developers Jorge Perez, Craig Robins, Norman Braman and Armando Codina have publicly denounced plans by the owners of Miami’s Magic City Casino to build a card room and jai alai arena on a site at 3030 Biscayne Boulevard they would lease from Crescent Heights.

The Real Deal reached out to Miami’s top builders to find out where they stood on the gambling measure. While several declined to comment, a handful weighed in, at right.