When Gloria and Emilio Estefan wanted to find a retreat away from South Florida in the early 2000s, they settled on an oceanfront house in Vero Beach. Soon after, the celebrity couple bought the Costa D’Este Beach Resort & Spa there, too.

In more recent years, other buyers from the tri-county region have also begun scooping up property in the seaside town just two-and-a-half hours up the coast yet far removed from the hustle and bustle of Miami.

“I discovered this great little town that is quaint and clean and uncluttered by development,” said Neli Santamarina, a Miami Beach-based real estate investor and close friend of the Estefans, who found the property for the couple and also bought a small hotel, the South Beach Place, in partnership with Miami Beach realtor Esther Percal.

In the past year, Sanatamarina, 62, has purchased other residential and commercial properties in Vero Beach. With 26 miles of beachfront along the Atlantic Ocean, the city has become an oasis for South Floridians — something akin to a Hamptons for Miami residents.

“There’s a lot of money in Vero, but it’s quiet money, not flashy money,” said Percal, 60, a senior vice president with EWM Realty International. “Way back when, it was where the people went who didn’t feel comfortable in Palm Beach.”

In Vero Beach, you can stroll by the water, dine at an oceanfront restaurant, visit a farmers market on Saturdays and buy oceanfront property for far less than you can in Miami.

“Even on that drive, you start to unwind,” said publicist Sissy DeMaria, 53, who has owned an oceanfront condo there for 13 years. “By the time you get there, you’re in another world. It’s a total decompression from the stress of Miami, the congestion of Miami, the pace of Miami.”

Recently though, DeMaria, Santamarina and others say they have noticed a younger demographic moving in, including couples in their 30s and 40s, and not just retired snowbirds. Now there are more hip restaurants and at least two bars that offer live rock music that are attracting a younger crowd.

But the area has retained its appeal as a remote getaway, DeMaria said. “Mostly, it’s private homes, and people get together and entertain a lot,” she said.

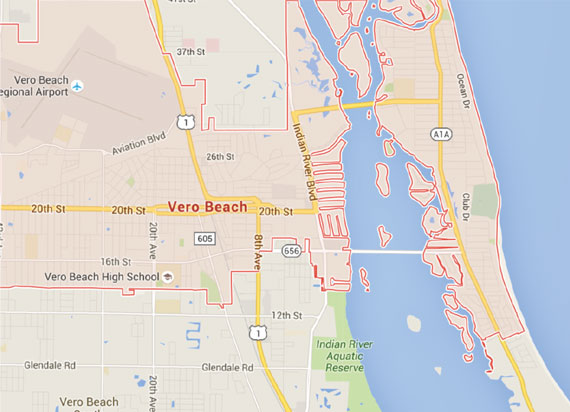

Vero Beach

Vero Beach lovers are keenly aware of the secret jewel they feel they have uncovered, and some are fearful of spreading the word. Yet at the same time, many in the real estate business can’t help but share their bounty, which means Vero Beach may soon become less hidden than it is now.

Residents “are always fearful of it becoming something they don’t want,” Santamarina said. “But people coming from the south come for what it is. We are not coming to change it.”

Jeff Morr, 52, visited Vero Beach the first time to see a college friend and told TRD he immediately fell in love in with it. “It has the quality and the beauty of Palm Beach, but without the pretense,” said Morr, a Miami-based realtor with Douglas Elliman and a real estate investor and developer.

Morr bought a house in Vero Beach about 200 feet from the ocean last year for $675,000 and has spent $450,000 to completely remodel it as a vacation home. The property is located next door to the home of author Carl Hiaasen, he said.

Others have bought property with the intention of retiring there. “I have had a few clients in Miami, long-term Miami people, that closed up shop and moved there totally,” Percal said.

Known perhaps best for its Indian River citrus, Vero Beach’s history is inextricably linked to the Henry Flagler’s Florida East Coast Railway, which began service through the county in 1893, according to the city’s website. Still, today Indian River County has a population of just under 150,000, while the city of Vero Beach has barely more than 16,000 residents, U.S. Census data shows. More than a quarter of the population was over 65 years old in 2010.

Cindy O’Dare, an associate broker with Premier Estate Properties, moved to Vero Beach from Miami about 25 years ago and told The Real Deal that she “has never looked back.” O’Dare, who focuses on the $1 million-plus luxury market, said she figures that more than 60 percent of her buyers are from Miami-Dade, Broward and Palm Beach counties.

“I am seeing a lot of people from Miami who want a second home but don’t want to get on a plane and fly somewhere. They love to have a weekend getaway,” she said.

“We are known as the Hamptons of Florida,” O’Dare added.

In fact, 2015 was her best year ever in 37 years in the real estate business, she said. O’Dare and her associate Clark French scored $168 million in sales, virtually all single-family homes and all in Vero Beach, last year. Generally, oceanfront homes are priced at $3 million up to about $10 million, O’Dare said.

At the same time, developers are taking note of the town’s growing allure. Among the latest projects, a townhouse development called Surf Club is currently under construction on a 2.5-acre oceanfront site. The 11 residences are priced at an average of $2.8 million, according to O’Dare, who has sold five of the units so far.

EWM’s Esther Percal.

Also on the ocean, the Brooklyn-based architecture and development firm Alloy Development is developing and designing 8050 Vero Beach, an 18-unit modernist-style condo project on five acres with 350 feet of ocean frontage. The project has recently launched sales, with prices starting at $3 million, according to Joey Arak, a spokesman for Alloy. Units there begin at 3,400 square feet, with the residences spread among three separate three-story buildings.

Alloy chose Vero Beach because its chief executive officer, Katherine McConvey, lives there most of the year, Arak said. McConvey’s eight-bedroom home, at 3700 Ocean Drive, is currently listed for $35 million and ranks as the most expensive home on the market.

Meanwhile, the developer of Windsor, a 416-acre island community in Vero Beach, recently broke ground on a new phase, called Windsor Park Residences, which will contain 12 condo units in three connected three-story buildings within the community planned by Miami town planners Andrés Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk.

But despite the ongoing development, many Vero Beach lovers point to the city’s strict zoning codes as part of the area’s appeal. Depending on the type of structure and area, developers are limited to building heights of 35 feet to 50 feet, or generally three to five stories. Those regulations have been in place since the 1970s, in response to two 12-story condo towers called Village Spires that were built on the beach.

“Those were the poster children,” said Timothy McGarry, planning and development director for the city of Vero Beach, in reference to the towers. “[Residents] clearly didn’t want the beach area to become like South Florida.”

Maintaining a balance with development is key, McGarry added.

“You have some people with expectations for more development and those who want Vero to stay Vero,” he said. “We are balancing it, but also trying to find opportunities without destroying the quality of life.”