As Amazon’s acquisition of Whole Foods threatens to upend the entire grocery sector, those currently sitting atop the retail food chain are working hard to solidify their standing.

Publix Super Markets, the dominant chain throughout Florida with 227 locations in the tri-county South Florida region alone, is doing just that. The company is making moves to ensure that it can weather any market challenges by increasingly becoming owners of their stores, as well as the shopping centers in which they operate. Analysts say the company buys the properties without borrowing, which lowers store occupancy costs. Buying up the shopping centers the supermarkets occupy also generates rental income from other tenants and allows Publix to limit next-door competition.

Publix is buying more than 30 stores a year nationwide, according to Mark Gilbert, executive managing director of investment sales with Cushman & Wakefield’s office in Miami’s Brickell area. In South Florida, since mid-2015, Publix has spent about $189 million to acquire eight shopping centers it anchors, plus about $45 million for two standalone supermarkets.

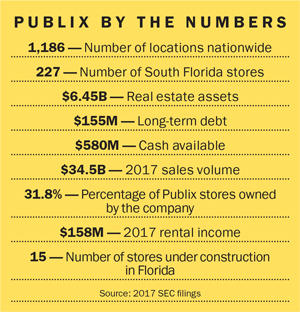

Although Publix is still a tenant at most of its 1,100-plus locations, which are spread across Georgia, Alabama, South Carolina, Tennessee, North Carolina, Virginia and Florida, the stores the company owns have accounted for a growing share of the total number since the Great Recession in the late 2000s, when many retail properties sold at distressed prices. The company owned 31.8 percent of its stores at the end of 2017, while 10 years earlier, it owned just 11.2 percent, according to an analysis by the Palm Beach Post.

Of course, operator-owned supermarkets are nothing new in the grocery industry. Aldi and Kroger, for example, own some of their stores, said David J. Livingston of Milwaukee-based supermarket consulting firm DJL Research. But unlike Publix, Livingston said, other grocers that acquire their supermarkets tend to borrow heavily — a risky strategy that loads interest expenses on top of operating costs in a low-margin business.

Take, for instance, the over-leveraged Winn-Dixie, a longtime Publix rival whose corporate parent, Southeastern Grocers, filed for bankruptcy this year. In connection with its Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing in March, Southeastern announced that 30 Winn-Dixie stores in Florida, including seven in Broward and Palm Beach counties, will close.

“They’re up to their eyeballs in debt. And that’s mostly on purpose,” Livingston said, “because there’s a private equity firm milking them for cash.” That firm, Lone Star, controls Southeastern Grocers’ supermarket operating subsidiary, which includes the Winn-Dixie business. Lone Star has extracted hefty, debt-funded dividends from the subsidiary, Bloomberg reported.

By contrast, Lakeland-based Publix had just $155 million of long-term debt and $580 million of cash at the end of 2017, according to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission filings the employee-owned company is required to file. It’s the highest-ranked Florida company in the Fortune 500, placing 89th in Fortune magazine’s 2018 list of the biggest U.S. companies by sales. Over the past four years, Publix has rung up annual sales of more than $30 billion and net earnings above $2 billion a year. The company’s profit margin on sales has been 6 percent or better in each of the last three years. “Most grocers are lucky to get 1 percent,” Livingston said.

Owning it

Publix has plowed cash into store acquisitions and upgrades because management has found few things “better to do with their cash than bet on themselves,” said David Moret, founder of Miami-based Highline Real Estate Capital, a shopping center investment firm.

In 2017, Publix remodeled 132 supermarkets. The company also had 34 new supermarkets under construction, including 15 in Florida, at the end of the year, according to the company’s filing with the SEC.

Publix began to accumulate shopping centers that it anchors to control their upkeep, Moret said, citing a source close to the company. “Originally, it was driven partially by a desire to control the quality of the experience for the shopper,” he said. People who have a bad experience at a Publix-anchored shopping center often blame the grocery company “whether they own the shopping center or not,” he said.

By becoming the landlord at shopping centers where it sells groceries, Publix gains control over the mix of co-tenants and can limit competition with its stores. The development of a new Publix-anchored shopping center may preclude the inclusion of a CVS or Walgreens pharmacy “because they [Publix] want to control the pharmacy,” Gilbert said. “Those are benefits above and beyond the real estate itself.”

Aside from operating rent-free, Publix also gets a tax break on the stores it owns in the Sunshine State. Retail tenants in Florida pay state sales tax on their rent. Assuming $500,000 of annual rent per store, that tax break would amount to $35,000 a year for each Florida store acquisition, according to Gilbert of Cushman. “It starts to add up really quickly,” he said.

Citing company policy, a Publix spokeswoman declined a request for comment from The Real Deal.

But public records shed light on the scope of its property acquisitions. The company’s 2017 annual report shows a surge in income from shopping centers where Publix is both the anchor and the owner. Rental income leapt from $95 million in 2015 to $158 million last year.

“To some extent, this is an investment alternative” for Publix, Gilbert said. “They effectively own some of the most valuable real estate in our neighborhoods.”