When South Korean immigrants Jin Sook and Do Won Chang landed at Los Angeles International Airport in 1981, they had nothing.

The couple eventually scraped together a modest savings and opened their first clothing store in Los Angeles. Over three decades later, they turned that single store into a fast-fashion empire known as Forever 21, which had 800 locations across the globe and at its peak was raking in $4.1 billion in annual sales.

Yet it was that rapid expansion that would lead to financial strain for Forever 21, due in part to its increasing number of large-format stores. Many of those were in malls and some in unprofitable markets, which have seen a steady drop in foot traffic from the onslaught of Amazon-led e-commerce.

That strain turned to ruin this week, when Forever 21 filed for bankruptcy.

In announcing it will shutter more than 175 stores in the U.S., the retailer leaves a host of mall landlords with millions of dollars in outstanding lease payments and millions of square feet of empty space.

For years, mall owners have been working to repurpose a glut of empty retail space left behind by challenged retailers. And in some cases, landlords are undertaking massive, expensive renovations to absorb these stores. But for the most part, when one retailer abandons a location, the property owner is left to replace that space with another retailer. That task has become increasingly difficult.

Mall owners on the hook

Some mall owners may be more exposed should Forever 21 close all of its stores.

Mall operator Westfield — which in 2018 was acquired by French shopping center operator Unibail-Rodamco — will feel the impact of the announced closures most. Eighteen of its Forever 21 stores in the U.S. will be closing their doors.

And combined, Macerich and Taubman Centers will see another 26 stores shut down.

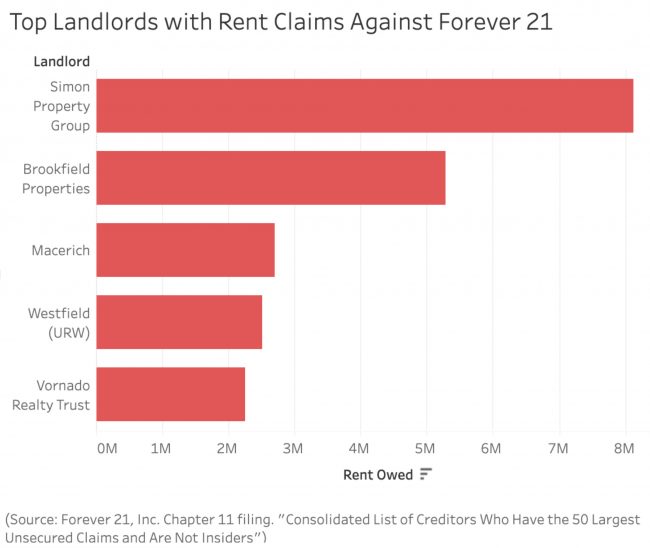

Unibail-Rodamco-Westfield, Macerich and three other landlords — Simon Property Group, Brookfield Properties and Vornado Realty Trust — also rank among the company’s 50 largest unsecured creditors, comprised mostly of vendors from Forever 21’s sprawling supply chain network in Asia.

Together, Forever 21 owes these five mall owners $20.9 million, bankruptcy court records show.

For Taubman, 4.3 percent of its malls’ gross leasable area comes from Forever 21, according to Mizuho Securities USA’s research from mid-September.

“It’s not small enough to ignore,” according to Mizuho managing director Haendel St. Juste. “This is meaningful.”

For Macerich, Forever 21 stores account for 2.5 percent of its average base rent, and for Simon Property Group, it’s 1.4 percent. Mizuho did not recommend a buy rating for any mall REIT in its coverage.

With 549 stores in the U.S., Forever 21 is a sizable tenant to many mall landlords. The stores, while smaller than anchor department stores, tend to span 40,000 to 60,000 square feet, larger than most inline stores, said Haendel St. Juste, managing director at Mizuho.

In an August report, Kroll analysts noted that among properties securing CMBS loans, 13 Forever 21 stores had floor area of 80,000 square feet or more, and were potentially at greater risk of “closure, downsizing or repurposing if determined to be inefficient.”

Coast to coast closures

The closures span the country, from the Forever 21 in the World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan, to the one at the recently-sold Hollywood and Highland Center on Hollywood Boulevard in LA. In between, they include Miami Beach, Midtown Equities’ 701 Lincoln Road.

The company’s restructuring “will focus on maximizing the value of our U.S. footprint and shuttering certain international locations,” Forever 21 said in a statement.

As part of its restructuring plan, Forever 21 said it will close most of its European and Asian stores plus at least 178 of its U.S. locations — a figure that could increase. The company also hopes to terminate lease agreements for another U.S. 11 locations that have not yet opened, including nine with Simon and two with Brookfield Retail, according to bankruptcy filings. Earlier this summer, a small group of Forever 21 officials sought to strike a deal with landlords Simon and Brookfield to invest in the company, an account the retailer denied, according to Bloomberg.

Scaling up and slowing down

By Forever 21’s own account, the company’s larger stores have been a drag on the company not just because of higher rents, but also because the need to fill those stores has strained its entire supply chain.

Today, though, it costs Forever 21 about $450 million to occupy its stores, which span 12.2 million square feet, court records show.

“The scale drove new merchandise sourcing strategy that greatly slowed ‘speed to market’ and increased risk generally,” according to the bankruptcy filing.

Forever 21 had expanded in the wake of the real estate crash of 2009, vacuuming up space left behind by Borders, Mervyns and Sears and locking in “advantageous prices” for rents, according to its court filings. And at that time, Forever 21’s low prices caught on with many consumers during an economic downturn.

Today, though, it costs Forever 21 about $450 million to occupy its stores, which span 12.2 million square feet, court records show.

The chain also claims in its filings that it is being hit hard by declining mall traffic and extra floor space for almost decade-old leases in unprofitable markets. The company also said it’s tight on cash, with just $19.4 million on hand, making it difficult for it to get the inventory it needs before the critical holiday season.

Race to repurpose

Forever 21’s bankruptcy filing comes amid a string of major retailer bankruptcies, including Barneys New York, Sears, Toys ‘R’ Us and Payless Shoesource. Year-to-date, U.S. retailers have said they would close almost 8,600 stores this year, compared to almost 5,800 last year, according to data firm Coresight Research.

The retail landlords are not out of the woods yet with the store closures, St. Juste said.

The retailer bankruptcies and closures have cast a long shadow on retail real estate owners, who must work to repurpose the big empty boxes left in the wake of a shuttered store. While REITs are outperforming the broader stock market, the regional mall sector is among the worst-performing REIT groups, posting one-year return losses of 13.5 percent, according to research released this week by Barclays.

Mall owners are trying to respond by repurposing and investing more money into aging properties. In Paramus, New Jersey, Westfield-Unibail-Rodamco plans to renovate the Garden State Plaza, one of the top malls in the country. Some of the new additions include residential space, offices and a hotel. And Macerich and Hudson Pacific Properties are also converting much of the the 500,000-square-foot Westside Pavilion in Los Angeles into creative office space, with Google as the sole tenant.

Still, as other retailers like Pier 1 Imports, DressBarn, JC Penney and Victoria’s Secret teeter near bankruptcy — according to Mizuho’s research — mall owners face a daunting road ahead.

“The retail landlords are not out of the woods yet with the store closures,” St. Juste said.