The pandemic has shone a harsh spotlight on office vacancies. The glut of space long predates Covid, though.

In fact, analysts and investors trace its origins all the way back to a Ronald Reagan era tax change, the Wall Street Journal reported. The change led to a building boom that ultimately outstripped demand for desk space.

In 1981, the Reagan administration changed the tax code in a bid to amp up the economy, for example, by allowing investors to depreciate commercial real estate at a faster pace. As a result, they put more money into office development than was justified by demand.

On top of that, developers found it easy to borrow money to build office projects, at least until the savings-and-loan crisis. From 1981 to 1989, completion of new office space in the top 50 markets topped 100 million square feet annually, peaking in 1985 at 182 million square feet, according to Moody’s Analytics.

Read more

While vacancy rates declined in the 1990s, the trend reversed with the Great Recession as companies slashed their office footprints to lower costs. Empty offices have been abundant since then, yet tax subsidies have continued to fuel office development.

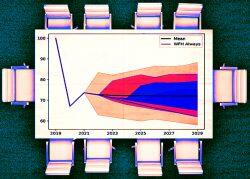

The office vacancy rate in the United States hasn’t dipped below 12 percent in the past 17 years, according to JLL. The 18.9 percent vacancy rate last quarter was the highest of that period.

Meanwhile, markets in the Asia-Pacific region and the Europe, Africa and Middle East regions have consistently had lower vacancy rates than their American counterparts. The rate was roughly 14 percent in Asia-Pacific last quarter and 7 percent in Europe, the Middle East and Africa.

The long-term nature of the problem, combined with the post-pandemic rise of remote work, means vacancy rates aren’t likely to ebb anytime soon. Meanwhile, a flight to quality has exacerbated the problem for older buildings, which for a variety of reasons are difficult to convert to other uses.

— Holden Walter-Warner