Sam Zell, the real estate investor who amassed an empire of apartment buildings, offices and mobile homes, earning the nickname “the grave dancer” for his ability to swoop up distressed real estate for a song, died Thursday. He was 81.

His death was announced by Equity Residential, the multifamily REIT he founded.

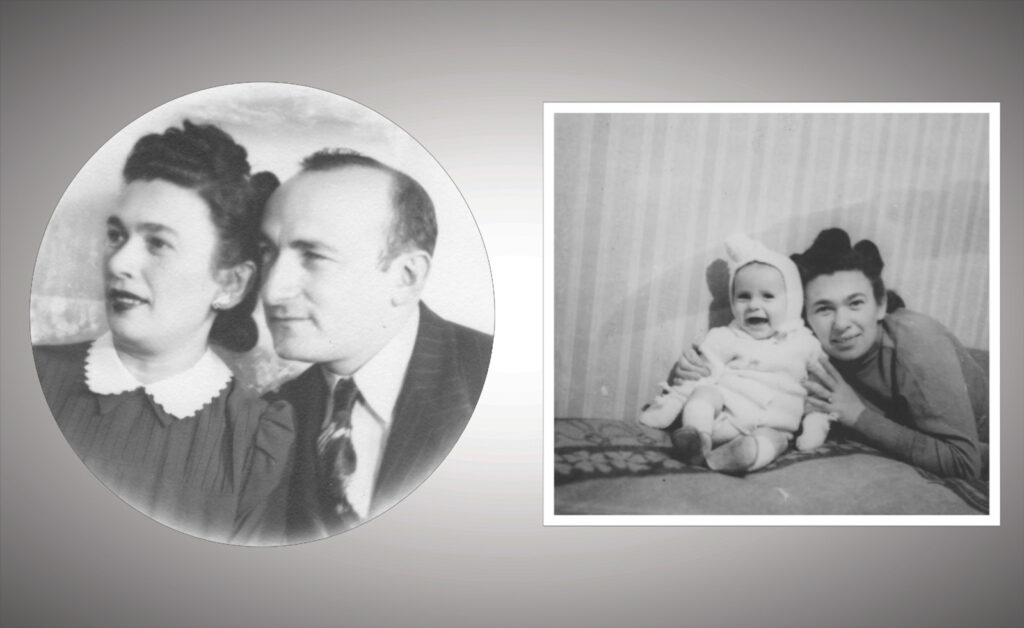

The son of Polish immigrants, Zell caught the entrepreneurial bug at a young age, selling Playboy magazines in the Chicago suburbs when he was 12. He broke into real estate in college, managing apartments for a landlord.

“We got another building and another and another,” he told The Real Deal in 2017. “Eventually, we started buying some, too.”

After graduating from law school, he tried his hand at his new white-collar profession — for a week.

“In my view, working is all about having a comparative advantage against other people,” Zell recalled of his legal stint, negotiating a contract for linens. “I didn’t see my comparative advantage in grunt work.”

He threw himself into real estate and stitched together a serious portfolio, including a collection of 573 office buildings he held under Equity Office Properties Trust. In one of the most consequential business deals of the generation, he sold Equity Office to Blackstone Group in 2007 for $39 billion — at the time the largest private equity deal in history.

Buy a motorcycle, Zell suggested to Jonathan Gray, the Blackstone executive who was the architect of the deal. The media, he explained to Gray, would be all over him after such a headline transaction, and Gray needed to give them a good hook.

“Sam was a legend in every way — a brilliant investor, entrepreneur and business builder,” Gray said in a statement to The Real Deal Thursday. “I loved his uniquely direct style and the example he set on how to live life to the fullest.”

Later in 2007, Zell made an ill-fated $8.2 billion purchase of the Tribune Company, a newspaper conglomerate. His approach to the business — slash costs and consolidate — made him the poster child for heartless corporate ownership of the media, and he received a barrage of negative press.

“At Sam Zell’s Tribune, Tales of a Bankrupt Culture,” read one story in the New York Times, in which reporter David Carr chronicled a company ridden with debt, starved of editorial resources, and dominated by frat-boy culture.

Years later, Zell identified the Tribune purchase as his worst-ever financial deal. But he was able to maintain some perspective.

“My goal is to be right seven out of 10 times. … I’m not going to get all hits, but what I’ve gotta do, and what a lot of other people in my field have not done well, is assess the scale of the risk. I start by saying, ‘Can I afford to lose it all?’”

In 2001, Chicago developer J. Paul Beitler and Zell were putting together a deal for a new skyscraper at 2 North Riverside, to be anchored by law firm Mayer Brown and accounting giant Deloitte. Zell’s talks with the prospective tenants were slated to be held in New York City, on Sept. 11.

The meeting started at about 10 a.m., just after the South Tower at the World Trade Center collapsed during the 9/11 attacks.

“We stopped the meeting every 45 minutes or so,” recalled Jay Neveloff, head of Kramer Levin’s real estate practice, who was representing one of the tenants. “There was never a moment where Sam said, ‘wait a second, the world’s ending.’ There was an acceptance by all of us that life would go on, and we’d have to deal with the horror. In a bizarre way, it was therapeutic.”

All flights were grounded, so for the return journey, Zell hopped in a limo to make the 800-mile trip back to Chicago. The proposal for the tower was scrapped in the wake of the attacks, as were dozens of new skyscraper projects nationwide.

“He didn’t have to question whether he was in favor of something or not,” Beitler said of Zell. “It was an immediate reaction and he stuck with it. More than anyone else in our industry, he was the one that really shaped how financing was able to advance.”

In 2016, Zell sold a 23,000-unit suburban rental portfolio to Barry Sternlicht’s Starwood Capital for $5.4 billion. Equity Group’s portfolio now includes over $30 billion in apartments, as well as interests in hotels, mobile homes — he was the largest investor in the asset class in the U.S. — logistics and health care. Zell stepped back from day-to-day leadership of his company, but dealmaking was a drug he never intended to give up.

“Retirement from what?” he replied when asked in 2017 about his future. “I don’t understand that, because I’ve never worked in my life. I’ve just done stuff that turns me on.”

Sam Lounsberry contributed reporting.