On a leafy May morning on the Lower East Side, a subcontractor stood idle at an untidy construction yard where an unfinished 28-story condo at 222 East Broadway sits.

Ready to work, he first needed permission from the project owner to begin installing the security system for the idealistic, 70-unit development. The project, developed by Optimum Asset Management where Chinatown blends with old Jewish tenement buildings, is a combination of a new ground-up structure and an old, abutting nursing home with art deco lines converted into 18 loft apartments.

“We want to move on to our next job, but we’re always waiting to get approval on this one,” the worker, who asked to remain anonymous, said. “There’s a cash flow problem. People be moving money in and out of the building so it’s hard to get things done.”

With the project a few years behind schedule, according to the contractor, sales launched last October. The timing wasn’t great: It was the first month that mortgage rates were consistently above 6 percent since 2008. Last quarter, 38 percent fewer homes sold in New York City than a year ago, according to Miller Samuel data.

The 222 East Broadway project illustrates the challenges new developments face in a slower market with higher interest rates, especially when construction loans come due and require refinancing with inventory loans. Extended sales timelines have fueled demand for such loans, which offer more attractive terms than construction debt and are secured by completed but unsold apartments.

“Survive ’til ’25 is the attitude among many developers,” said Ran Eliasaf, CEO of the heavy-hitting lender Northwind Group. Eliasaf and other lenders expect interest rates to peak this year and decline in 2024 or 2025.

Inventory loans help developers buy time.

Don’t fret, buy debt

“A misconception about inventory loans,” said Stephen Kliegerman of Brown Harris Stevens Development Marketing, “is that they mean there’s a problem.”

Alternatively, they may be a sign of health because “the new lender can offer lower rates and be more confident in making a better return,” Kliegerman said.

Following completion, lenders can refinance debt at lower interest rates, typically a point or two less, and transition to a fixed rate from a variable one because they perceive less risk.

Inventory loans allow developers to finish their punch list, pay carrying costs including an interest reserve and fund a marketing campaign to help sell units.

Kliegerman’s firm shepherds new development projects from land acquisition to construction, helping obtain the most debt possible and setting the stage for what will be refinanced once construction wraps and apartments are ready to list.

For projects such as Extell’s One Manhattan Square and Chris Xu’s Skyline Tower, each of which have more than 800 units, developers can expect one or two inventory loans, given the naturally longer sales timelines. Even at a brisk pace of selling 100 units per year, the city’s largest projects can take nearly a decade to sell out.

Inventory loans can also return money to investors before a building is sufficiently sold.

That may have been the case in April, when China’s Risland took on a $60 million inventory loan at Skyline Tower nine months after completing a bulk condo purchase in the building. And Extell’s Central Park Tower recently got a $500 million inventory loan shortly before $380 million in private equity mezzanine loans was set to mature.

While slower sales may spur the market for inventory loans, there is less available inventory now than before the pandemic, data from Miller Samuel show.

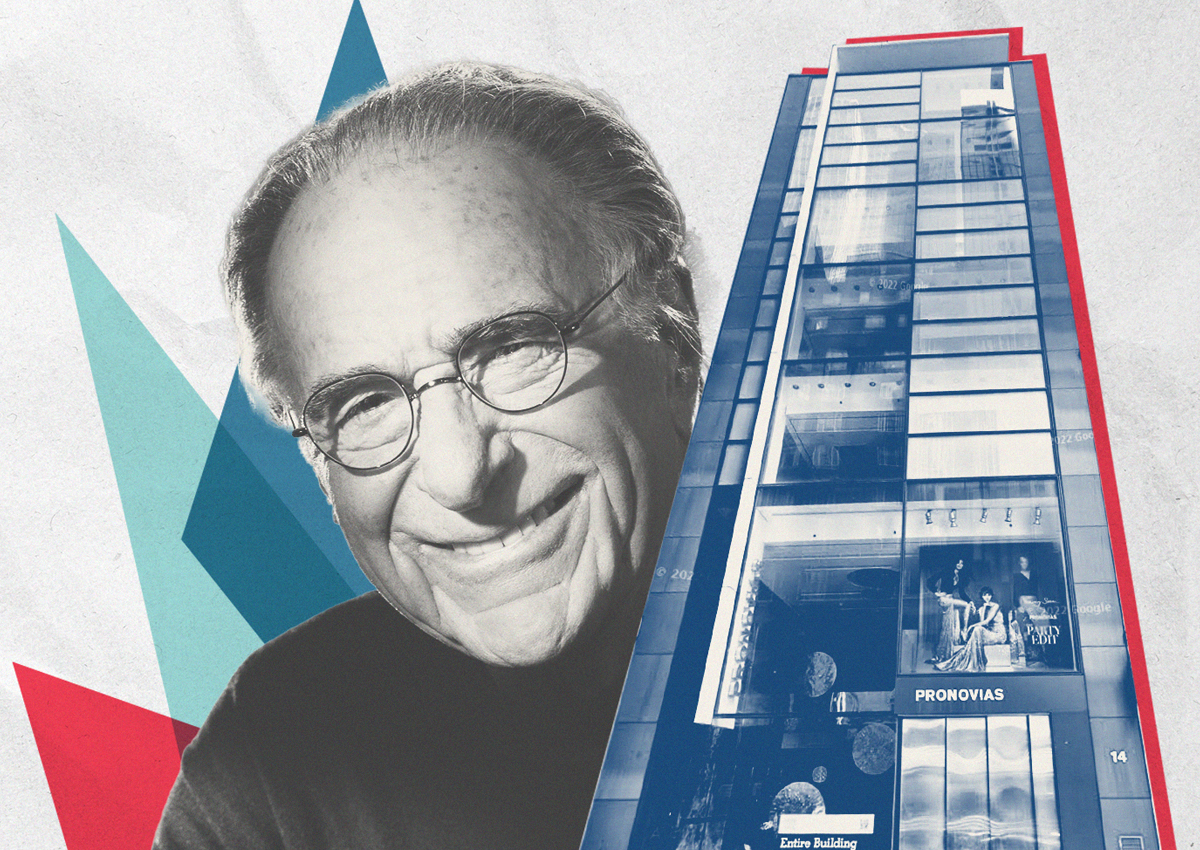

“Not a lot of supply is coming to market now,” said Meridian Capital Group’s Morris Betesh, who recalled 2018 and 2019 as more active years for inventory lenders. “Lenders with capital are competing for fewer transactions.”

Time management

Whether Optimum’s East Broadway project is well suited for an inventory loan largely depends on when its construction debt comes due. A typical term is 24 to 36 months.

With sales underway at the project’s ground-up building and just four units listed as in contract on StreetEasy, companies involved with the project are staying quiet.

Optimum, Madison Realty, which lent $40 million in 2021 to build the project, and the brokerage responsible for sales, Cantor & Pecorella, all declined to comment.

“When the market is slow like right now, projects need more time to sell,” said Northwind’s Eliasaf. “Construction lenders typically want out after extensions and banks are scaling back,” leaving private shops like his to make more inventory loans.

“The next three years look sound from a supply and demand perspective,” Eliasaf said of the new condo market. “There is no real reason for prices to go down.”

Still, challenges remain.

“Buyers don’t want to borrow at 6 percent,” said Seth Weissman, founder of Urban Standard Capital, inventory lender at 199 Chrystie Street, a 14-unit project on the Lower East Side.

Read more

“The larger the floor plates are for units, the tougher it is to move the inventory,” said Eliasaf, identifying modestly priced projects as the sweet spot for lenders. “$1.5 million [per unit] is what we really like,” he said.

Still, Weissman believes developers can move product: “If buyers take advantage of concessions and can refinance in 18 to 24 months, they will have bought at a discount.”