Middle-income rental buildings are all the rage these days among some of the country’s biggest real estate investors. Take the Blackstone Group, which recently dished out $700 million for the Caiola family’s Manhattan portfolio, or the Related Cos. stealth acquisitions of multifamily properties in Brooklyn and the Bronx. On Monday, Barry Sternlicht’s Starwood Waypoint Residential Trust merged with Colony Homes in another giant bet on the rental market. Why are these investors so gaga over rentals?

Observers point to two trends making rental housing a good investment – one national, and one New York-specific.

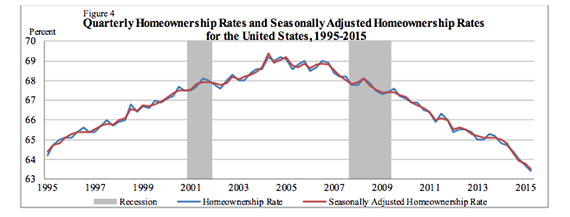

Since at least 2004, low- and middle-income households across the United States have been shifting away from homeownership, according to Trulia’s chief economist Selma Hepp. The 2008 housing crisis may have accelerated the trend, but its roots are structural: Stagnating real incomes that, coupled with the ballooning cost of healthcare and education and stricter mortgage lending standards, keep homeownership out of reach for a growing share of the population.

(Credit: U.S. Census Bureau)

“Being able to save for a down payment seems to be a big issue for [the millennial] generation.” Hepp said. “That, combined with lack of access to credit, is impacting homeownership.”

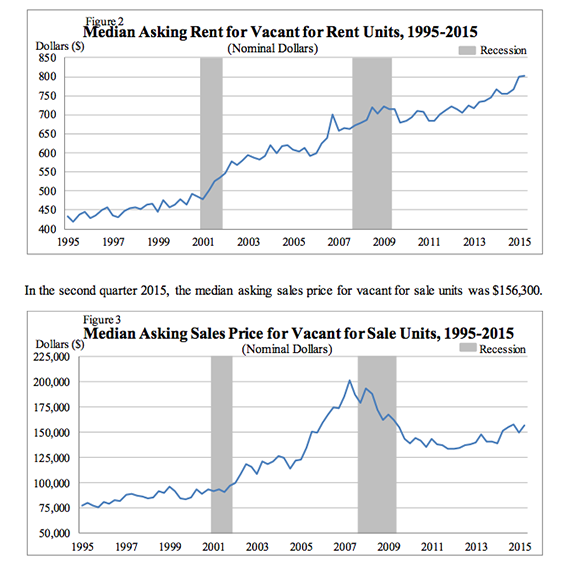

These factors push demand for rentals up, but supply of new rental product remains low following the recession. As a result, median rents have been climbing, at a quicker pace than both family incomes and inflation. For millions of “everyday Americans,” this means a painful dent in living standards. For firms like Blackstone and Starwood, it’s a chance to make a lot of money (see chart below).

(Credit: U.S. Census Bureau)

New York City, which has always been a renters’ town, is facing the same forces. “Rents rising is tied to tight credit,” said Jonathan Miller, CEO of Miller Samuel. ‘There’s a dearth of first-time buyers, and many are bumped into the rental market.” Brooklyn’s median rent topped $3,000 in August – a new record, according to the latest Douglas Elliman report.

But the Big Apple is experiencing another trend that thrills owners of rentals: the ballooning cost of land. “I think developers are having a tough time penciling out the numbers on rentals,” said Jason Silverstein, co-founder of investment firm Silvershore Properties. It’s a common complaint that Manhattan’s high land prices make rental projects unfeasible here, pushing developers to go the luxury-condo route and making existing rental stock even more valuable. This, at least, appears to be why firms like Blackstone are, in Miller’s words, “playing out the logical follow to the luxury condo boom.”

Daniel Parker, a broker at Hodges Ward Elliott, said the “smart institutional money” is wagering on housing for middle-income earners “because it offers attractive yields no longer available in the high-end condo or rental markets.”

Blackstone, a company that has been able to consistent generate double-digit returns since the crisis, exemplifies this strategy. In July, it bought 25 apartment buildings from the Caiola family in partnership with Fairstead Capital. The buildings are clustered in Chelsea and the Upper East Side – two areas that have seen a lot of luxury condo construction. Nationwide, Blackstone owns about 50,000 single-family homes, which it bought following the financial crisis and turned into rentals.

“In terms of our business, we are 97 percent occupied. We are seeing 4-plus percent rental growth, “ Blackstone’s head of real estate Jonathan Gray told CNBC in July. “We think it’s a real business.”