Crowdfunding startup Fundrise calls its newest real estate investment product “the biggest technological innovation in the history of finance.” And that’s far from the only apparent exaggeration it is using to drum up investor interest in its new mortgage REIT.

Fundrise is selectively using facts and figures on its website in a way that may make its product look more attractive than it actually is – at least to many of the lay investors it is explicitly targeting. Though the practice appears to be legal, it raises a troubling question long on the minds of industry observers: is crowdfunding sufficiently regulated to protect mom-and-pop investors?

The three-year-old firm, which has raised $41 million in venture funding and is backed by industry heavyweights like Silverstein Properties’ Marty Burger and the Ackman-Ziff Real Estate Group, crowdfunds real estate projects by allowing both accredited and unaccredited investors to invest through its website. Last week, it launched a non-listed mortgage REIT. Unlike other non-listed trusts, the so-called eREIT is regulated under Regulation A under the JOBS Act, which allows investors to buy shares online without having to go through a registered broker-dealer.

The eREIT was released with much fanfare — mass promotional emails had subject lines such as “!!!” and “It’s almost time!” The selling point of the new product was meant to be its transparency, with potential investors able to review detailed information about Fundrise’s strategy and track record online.

“It’s no more challenging than buying a book,” Fundrise’s COO Brandon Jenkins told Wired.

The problem, however, is that the stakes are far higher than deciding between the latest potboiler from Stieg Larsson or James Patterson. Fundrise is marketing its product as a good place for mom-and-pop investors to put their money. The company claims that just four hours after it launched its eREIT, it was oversubscribed by over 400 percent. It now plans to re-open its offering to accept another $2 million in investment into the eREIT.

But a review of its website and a closer look at the product reveals that these investors may not be getting the whole picture.

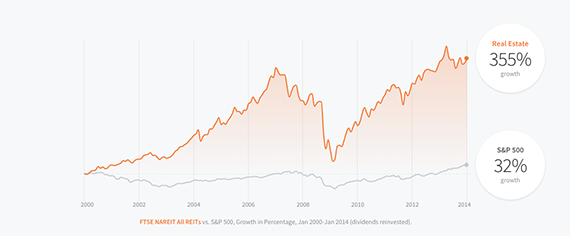

1) Real estate vs. S&P 500 – A matter of perspective

The first chart (seen above) compares the growth of the S&P 500 stock index with the most commonly used REIT index, starting from the year 2000. To the lay observer, this chart gives the impression that investing in a typical REIT is 10 times more profitable than investing in a typical corporate stock.

The first chart (seen above) compares the growth of the S&P 500 stock index with the most commonly used REIT index, starting from the year 2000. To the lay observer, this chart gives the impression that investing in a typical REIT is 10 times more profitable than investing in a typical corporate stock.

But by picking the year 2000 as its starting point, Fundrise chose a period where the difference between REIT and S&P 500 returns was unusually large. If it had picked, say, the past decade, REIT returns (206%) would have outpaced the S&P 500 (175%) by a much smaller margin. And since early 2009, when the current market upswing began, the S&P 500 has actually outperformed the REIT index.

These caveats are not easily visible in the chart and may be lost on many lay investors. Fundrise offers no disclaimer.

In an interview with The Real Deal, Ben Miller, Fundrise’s co-founder and CEO, dismissed the suggestion that his company cherry-picked the period most favorable to real estate. Asked why Fundrise chose the year 2000 as its starting point, he said: “It seems like a natural place to start.”

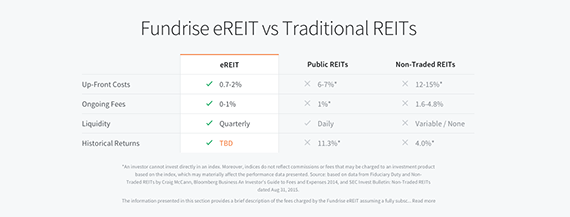

2) Fee fi fo fum

The second chart (above) shows the fees Fundrise charges its investors. The chart gives the impression that fees will not be higher than 2 percent up front and 1 percent annually. But that’s not necessarily the case.

The second chart (above) shows the fees Fundrise charges its investors. The chart gives the impression that fees will not be higher than 2 percent up front and 1 percent annually. But that’s not necessarily the case.

The fine print underneath the chart states that the fees shown are based on the assumption that Fundrise raises the full $50 million it plans to raise. If it doesn’t reach its target, the upfront fees can be significantly higher than 2 percent. And neither chart nor fine print mention a number of “expense reimbursement” provisions in the eREIT’s SEC filing, which could further drive up net fees.

Asked to comment, Miller wrote: “Just as with any major REIT or private real estate fund the percentage of the upfront costs will vary depending on the total proceeds – they could be higher or lower.”

He continued: “At the end of the day the Fundrise eREIT lets individuals invest directly in commercial real estate with fewer middlemen and lower fees than any other public or private real estate investment. We are incentivized to deliver and don’t get paid an asset management fees for 2 years unless our investors earn a 15% annualized return.”

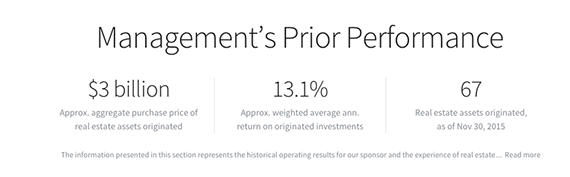

3) Fundrise’s track record

The third chart (above) claims to show Fundrise’s prior performance. The number that immediately stands out is $3 billion, which Fundrise calls the “approx. aggregate purchase price of real estate assets originated.”

The third chart (above) claims to show Fundrise’s prior performance. The number that immediately stands out is $3 billion, which Fundrise calls the “approx. aggregate purchase price of real estate assets originated.”

To lay investors not well-versed in finance-speak, this chart may give the impression that Fundrise has raised and invested $3 billion – a stately sum. In fact, SEC filings show that Fundrise has raised $58.3 million for real estate projects over the three years of its existence, or less than 2 percent of the stated $3 billion.

The company appears to have got to the $3 billion figure by including the full value of 3 WTC, Silverstein Properties’ $2.5 billion-plus office project in Lower Manhattan. Fundrise bought $5 million in liberty bonds used to fund the project on the secondary market (i.e. from someone who had previously bought them from Silverstein) and then offered them for re-sale to its investors.

Silverstein Properties’ President Tal Kerret is Fundrise’s independent board director. The development firm declined to comment for this article.

Asked why Fundrise didn’t include the actual amount it has raised, and whether that would more accurately portray its performance, Miller responded: “I think it’s more accurate what we wrote.”

Other prominent crowdfunding players, however, have opted to go a different route. California-based Patch of Land prominently displays on its website the total value of projects it has been involved in and the amount of money it has raised. Realty Mogul also prominently displays both the value of projects funded and the much more modest sum it has actually raised on its website.

The risks of lax regulation

Taken together, the selective presentation on the eREIT’s website paints an overly rosy picture of Fundrise, which could make it harder for lay investors to make an informed decision. Though the strategy appears to be legal, it does raise concerns over whether small-time investors are sufficiently protected under current crowdfunding rules.

Securities crowdfunding, or funding projects with the help of a large number of small-time investors, has been around for centuries. But the sale of securities was little regulated, leading to widespread fraud during the stock market boom of the 1920s. In 1933, aiming to better protect investors, Congress passed the Securities Act, which mandated that all sellers of securities file with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and that certain private placements only be sold through broker-dealers. The law effectively ended securities crowdfunding in the United States.

The passage of the JOBS Act in 2012 made the practice legal again, but regulators have been careful to avoid the mistakes of the past and protect investors. Unaccredited investors face limits on how much they can invest through crowdfunding platforms, while the platforms have strict guidelines on the disclosures they need to make in SEC filings for their offerings.

But these rules still leave a massive blind spot: there are currently no crowdfunding advertising laws that mandate what kind of information firms like Fundrise have to include on their website, according to Richard Morris, an attorney at Herrick, Feinstein who specializes in securities law. While Fundrise has to include information on how much money it has raised or its exact fee policy in its voluminous SEC offering (which is linked to on the eREIT’s website), it doesn’t need to do the same on its website.

Contrast that to other consumer-facing industries, such as pharmaceuticals, where firms are required to mention possible side effects in TV advertisements. Consumers can’t be expected to pore through the fine print, the logic goes, and need to be protected from making potentially dangerous decisions. There is no equivalent for crowdfunding websites, even though investors may be putting their savings at risk.

“Advertising rules are restricted to securities laws,” said Morris, who did not comment directly on Fundrise. “What might be interesting as more and more general solicitations are being done in a public way is the next question, which is what other consumer type of laws might be applicable.”

The question carries great importance for the real estate industry. New, much-hyped and lightly-regulated fields like crowdfunding are vulnerable to adverse selection. In the absence of objective information, those players who make the most ambitious promises often lure the most investors. If things go sour, the credibility of the entire industry could be hurt.

Fundrise is, according to many observers, a well-respected company whose offerings are innovative and offer investors a real benefit.

But by cherry-picking numbers to hype up its product, it may be opening the door for other, less reputable platforms to do the same.

“Down the road there will be people who don’t give robust advertisements and more or less tease people,” Morris said. “If people started doing that you can imagine states and the SEC coming together to give more specific advertising rules on a stand-alone basis.”