In an attempt to pinpoint the source of funds pouring into New York real estate, the U.S. Treasury said Wednesday it would start tracking luxury all-cash property purchases made through shell companies.

“We are concerned about the possibility that dirty money is being put into luxury real estate,” Jennifer Shasky Calvery, a top Treasury official, told the New York Times, explaining the decision.

The Real Deal spoke to many top players across the real estate ecosystem to get their take. Some said the move is likely to cause major heartburn for an industry that has long benefited from relative opacity and minimal regulation. Others reacted with nonchalance, characterizing the initiative as a minor annoyance. But among the varied reactions one common theme emerged: confusion.

Under the Treasury’s new rules, title insurance companies will, for the first time, be required to discover and disclose the identities of buyers to the government. The initiative will only apply to Manhattan all-cash transactions that are north of $3 million and done through LLCs. But given that a large chunk of Manhattan deals meet those criteria, the impact could be significant.

Michael Graves, a Douglas Elliman broker who said the bulk of his deals above $8 million are all-cash LLC trades, believes only a tiny fraction of purchases are done with filthy lucre.

“The vast majority of these transactions are simply people who want to protect their identities for the safety of themselves and their family,” he said. “By and large, the Feds will find it’s a witch hunt.”

How many properties are impacted?

Nearly 1,700 Manhattan properties currently on the market are asking $3 million or more, according to StreetEasy. Over the past 12 months, there were nearly 1,800 closed sales above $3 million. During the second half of 2015, residential sales of $3 million-plus pads added up to $6.5 billion, according to PropertyShark data cited by the Times.

And while the median price in Manhattan has inched higher in recent months, new development condos – the products of choice for foreign buyers – have seen larger price gains.

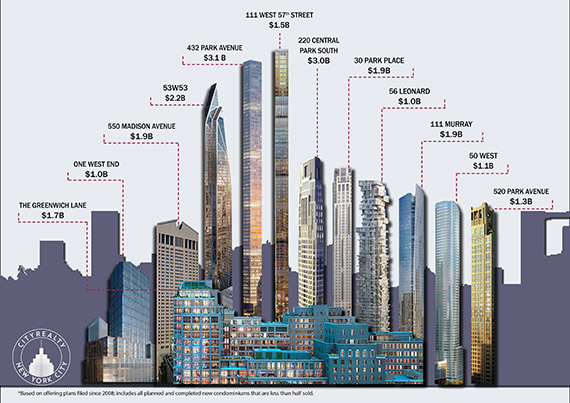

Manhattan’s priciest new developments by total sellout (Credit: CityRealty)

During the fourth quarter of 2015, the average Manhattan sales price was $1.9 million, compared to the average new development sales price of $3.3 million, according to data from appraisal firm Miller Samuel. And CityRealty estimates that roughly 1,300 new development units in the pipeline are priced at $3 million or higher.

The traveler’s dilemma

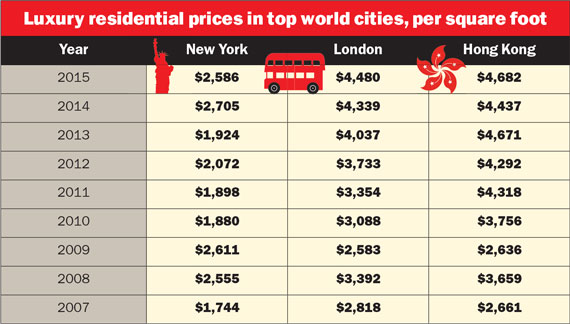

Foreign buyers’ ever-increasing clout in New York’s luxury market has been well documented, and sources said it’s this influx of global capital that is the focus of the Treasury’s initiative.

Luxury residential prices in world cities, psf (Source: TRData)

“International purchasers have been driving a lot of the higher-end real estate over the last few years,” said Terrence Oved, a founding partner at law firm Oved & Oved. “The Goldman Sachs bond trader who, 10 to 15 years ago got a bonus in December, is not buying the penthouse at [Extell Development’s] One57,” he added. “A lot of these people are international purchasers and many of them, for a lot of reasons, prefer to have their identities shielded.”

Bob Axelrod, a director of Deloitte’s anti-money laundering practice, said “one of the classic ways to launder money is by buying real estate, because real estate transactions frequently do have ways of shielding the ultimate owner from publicity.”

[vision_pullquote style=”1″ align=””] “By and large, the Feds will find it’s a witch hunt.”- Michael Graves, Douglas Elliman [/vision_pullquote]

The government, he added, “is now looking to address this.”

In July, Mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration launched its own attempt to increase transparency in the luxury market, requiring members of shell companies to disclose their names to the city . On Wednesday, the Treasury said its new requirement, which will launch on a trial basis from March through August, would become permanent if officials feel there is widespread jiggery-pokery.

Patrick Fallon, a senior Federal Bureau of Investigation official, told the Times that the Treasury initiative would help expose illegal activity.

“We fully intend to encourage expansion of it [the initiative], Fallon said, “not only to different geographic areas but as far as the time frame as well. We think it’ll prove its worth.”

What part does everyone play?

Stuart Siegel, president and CEO of Engel & Völkers New York City, said the government’s attempt to trace illicit funds that buy U.S. real estate was “honorable,” particularly “given the world economic and security situation.” But he questioned what role agents would play.

“Does the broker have to identify the source of the funds? We certainly don’t have that ability or capacity,” he said. Siegel said some of his agents work with representatives of buyers, and don’t know the identity of the true buyer. “What we do know is whether that client has the capacity and is bona fide, that they can pay the price,” he said.

Leaders in the title insurance industry, who bear the brunt of the disclosure requirements, also expressed uncertainty about the new policy. In a letter sent Jan. 13 to the Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, the American Land Title Association (ALTA), a trade group representing the title industry, called for several clarifications to the policy. The letter, which was sent by ALTA CEO Michelle Korsmo and reviewed by TRD, called on the Treasury Dept. to limit the order to residential units and urged the government “to use a reasonable and good-faith test for determining insurers’ compliance” with the order.

“Even with the best efforts of title insurers, there may be transactions of which the insurer is not aware,” the letter stated.

Too soon to tell

Adding these disclosure requirements, said Miller Samuel president Jonathan Miller, could cause hiccups in a high-end market that’s already showing signs of softening.

“The problem is that you’re casting this blanket of uncertainty over a market that’s already slowed from a year ago, based on some small percentage of bad players,” he said. “The best-case scenario is that it has no impact [on sales]. The worst case is that it slows down the activity a little bit until people feel comfortable about it. The consumer is probably going to wait six months to see if this renews.”

Oved said the requirement would cast a shadow on LLC deals — even routine, innocent ones that account for a large share of activity in the Manhattan property market.

“It’s almost like the requirement for people to go through security checks at the airport,” he said. “Someone who’s carrying contraband is going to feel more nervous, but it will have a negative effect on the regular person who’d rather not get padded down. It may cause developers, sellers and brokers to think again in terms of where their ultimate consumer is coming from.”

But others were far more optimistic.

“We think that this will have little effect on the market,” said Howard Lorber, chair of Douglas Elliman and an increasingly active developer. “It is de minimis and will not have a significant impact.”

Some said the Treasury’s move was hardly surprising.

“Look, when you buy a $50, $60, $70 million apartment, the world takes notice,” said Jonathan Adelsberg of law firm Herrick, Feinstein. “Do I think ultimately disclosing who owns property will stifle the purchase of units? Maybe initially, but long-term, no.

A certain pool of wealthy foreign buyers will keep coming here, he said, “because New York is a safe, secure environment. If you have that kind of money, there are other disclosures you have to worry about.”