My wife and I recently looked at homes around Washington D.C. We were shocked. Prices in many D.C. suburbs are 30 percent to 50 percent higher than they were five years ago. We visited Seattle over Christmas and found the same: Prices are up anywhere from 30 percent to 70 percent since 2009.

D.C. and Seattle are big, wealthy, cities. But almost everywhere around the country, homes prices are surging. Nationwide average home prices are up 30 percent since bottoming in 2012. They’re now just 4.5 percent off their 2006 bubble highs, according to data from Yale economist Robert Shiller. Even adjusted for inflation, average prices are back to where they were in 2004 — a year most would consider as firmly part of the housing bubble.

San Francisco prices are up 79.2 percent since 2009. Atlanta is up 53 percent. Phoenix, up 47.1 percent. Denver, 42.6 percent. Los Angeles, 49.7 percent. The magnitude of these gains rivals what we saw during the nuttiest portions of the 2000s bubble.

It’s crazy. And it’s underreported, likely because we’re still shell-shocked from the housing crash.

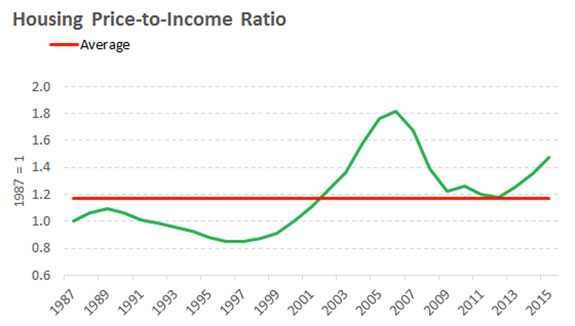

Average home prices can’t sustainably rise faster than average incomes, especially if interest rates are rising (which they are). But look where we’re at: well above average and rising:

As a percentage of median income, recent price gains have brought us almost halfway back to the 2006 bubble peak.

Don’t call this a bubble — mortgage borrowing is still low by historic standards — but things are changing. Consider a new type of mortgage San Francisco Federal Credit Union recently promoted. In response to “skyrocketing home prices” hampering affordability, the bank is offering a no-money-down mortgage with an adjustable interest rate and without requiring private mortgage insurance. Even 2005’s mortgage market would blush at those terms.

All real estate is local, so your house might be just fine. Everyone has a different housing story.

But we should ask: Why are home prices rising so quickly?

People talk about low interest rates, Fannie and Freddie, bad policy, etc. All play a role. And, of course, we’re coming out of the worst housing downturn in modern history. But three other forces catch my attention.

One, home construction was historically dominated by mom-and-pop construction crews. Today, corporate home builders play a big role in nationwide construction. And large homebuilders do something small contractors don’t: Work with huge, multi-hundred-home developments rather than single-home projects. This lets them easily restrict the supply of new homes to maximize profits. Big builders also tend to focus on large and expensive homes, where profit margins are fattest. And since so many contractors went out of business during the recession, the existing players have a tighter grip on supply. When prices started rising in 2013, 60 percent of homebuilders said they were intentionally slowing the pace of sales to maximize prices, according to housing research firm Zelman & Associates. This might fundamentally change the dynamic of real estate pricing in ways we didn’t see over the last 100 years. That’s what happens when homebuilders go from being run by contractors to MBAs.

Two, new homes require new schools, new reservoirs, new roads, and new sewers. Those cost cities and counties — with finances still clobbered by the recession — upfront money they don’t have and can’t borrow, even if new homes bring in property taxes down the road. So cities often restrict new-home permits to reduce municipal expenses. The Boston Globe recently reported:

Cities and towns, frequently citing added school costs, continue to either oppose new housing or accept it only reluctantly, allowing just enough to meet state affordable housing mandates and imposing restrictions that limit the types of homes that can be built. More than six years after the last recession, the state is building only about half the housing it did in 2005, the peak of the last boom.

Three, population growth has shifted from suburbs to cities. This is driven in part by the decline of factories (located in rural areas) and the rise of information jobs (located in cities), and in part by millennials rejecting the commuting lifestyles of their parents. It’s a big shift: Suburbs grew faster than cities every decade from 1920 to 2010, according to the Census Bureau. That ground to a halt, as more than half of large cities are now growing faster than the nation’s suburbs. As more people compete for homes in smaller geographic regions, prices shoot up. San Francisco is an extreme example, but the same pressures are playing out in Austin, Denver, D.C., and Seattle.

If you called housing a bubble in 2003, you were right. But it took another three or four years for prices to peak. We can look at prices today and say things look crazy, but forecasting what might happen next is nearly impossible. Here’s how I think about housing:

- A home is a great place to live. Historically, it’s been a lousy investment. Here’s a look at the long-term data, including an interview I did with Robert Shiller. Keeping your expectations in check is key in any investment, but especially housing, where emotions mix with leverage and social status.

- If you’re not going to live in a home for at least five to seven years, you’re exposed to lots of variability. This is just like the stock market.The ability to wait out crazy fluctuations is your best defense in all investments, including housing.This is especially true when you break down how most mortgages amortize: Before 10 to 15 years of ownership, the large majority of your monthly payment is interest. And most people can’t write off interest from their taxes, since they take the standard deduction rather than itemize.

- Put these together, and a smart home philosophy is to ask: Is This Home A Good Place to live, raise my family, and live for a decade or more? If it is, great. People get into trouble when they ask, “Is this the right time to buy/sell based on market conditions?” Your odds of timing housing are no better than timing the stock market.