Over the past few years, as New York’s commercial real estate market kept trying to outdo itself, CMBS lenders provided a big portion of the money fuelling the boom. But in early 2016, new commercial mortgage-backed securities have largely retreated from Manhattan, leaving property investors with fewer financing options and further spooking an already nervous market.

Over the past few years, as New York’s commercial real estate market kept trying to outdo itself, CMBS lenders provided a big portion of the money fuelling the boom. But in early 2016, new commercial mortgage-backed securities have largely retreated from Manhattan, leaving property investors with fewer financing options and further spooking an already nervous market.

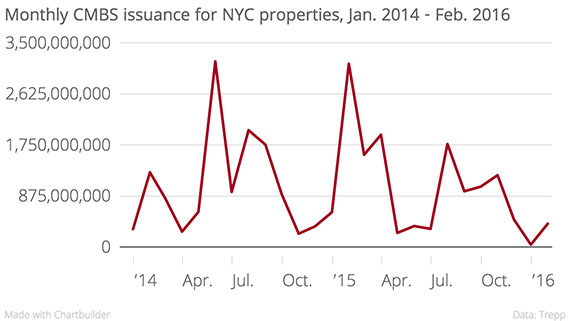

Manhattan CMBS issuance has been declining since mid-2015, after a strong start to that year and hit a two-year low of $40 million in January before recovering slightly in February, according to CMBS research firm Trepp. Uncertainty in global bond markets was the main reason for the slump.

On Feb. 9, mid-sized CMBS lender Redwood announced it would stop issuing new loans. “We have concluded that the challenging market conditions our CMBS conduit has faced over the past few quarters are worsening and are not likely to improve for the foreseeable future,” the firm’s CEO Marty Hughes said in a statement. Others may soon follow suit.

“2016 kind of began with an air of pessimism,” said Sean Barrie, a research analyst at Trepp, adding that he expects small CMBS lenders to be hardest hit. “A couple of small [CMBS] shops had started to kind of close up and that’s going to happen more with players with very little skin in the game,” he said.

CMBS 101

First, a quick primer on how securitization works: CMBS firms issue real estate loans, repackage these loans as bonds and then sell them off to investors. The yield (return on investment) bond investors are willing to accept determines the interest rates CMBS lenders can offer to their borrowers.

For example, if a CMBS issuer believes that investors will buy CMBS bonds at a yield of 6 percent, it will have to charge its borrowers an average interest rate of at least 6 percent for the underlying loans. Any rate lower than that, the issuer would lose money.

Over the past couple years, bullish bond investors were willing to accept extremely low yields on CMBS, in part because loose monetary policies around the globe had pushed down interest rates. This in turn meant CMBS lenders could offer borrowers low interest rates on loans, expanding their market share and offering real estate investors a cheap way of funding acquisitions and refinancing their existing portfolios.

The recent global stock and bond market turmoil, which began in mid-2015 but really accelerated over the past few weeks, put an end to the party. Over the past year, the average spread between five-year AAA CMBS bonds and U.S. Treasury notes grew by 75 percent. In other words: bond investors spooked by the worsening global economic outlook are now willing to pay less for CMBS and demand higher yields. By extension, this means CMBS lenders have to charge borrowers higher interest rates, making them a less competitive source of real estate financing.

Frequent changes in bond yields have added another challenge. “There’s no stability in the market, it’s just so hard for people to price loans accordingly,” said JLL’s Kellogg Gaines. In order to price a loan, CMBS issuers need to have a sense of what kind of yields the bond market will command weeks or months from now, when the loan gets securitized. Volatility makes that tough, leading some to hold back on issuing loans. “Certain lenders have trouble understanding the market,” said Gaines.

And finally, under new federal rules that kick in at the end of the year, CMBS issuers will have to keep a portion of the loans they issue on their own balance sheets. This so-called “risk retention” policy, designed to discourage reckless lending, increases issuers’ cost of capital, and Trepp’s Barrie called it a “main impetus” behind the CMBS slowdown.

What does all this mean for the New York real estate market?

For these reasons, CMBS lenders have lost much of their glitter in Manhattan. Avison Young’s David Eyzenberg said he is currently arranging financing for a retail property that in the past would have been a shoo-in for CMBS. But now, no bids from CMBS lenders came in.

If bond markets stabilize, CMBS could yet make a triumphant return. But for now, the city’s real estate players will have to look elsewhere for funds.

Since January 2014, $26.7 billion worth of CMBS loans for Manhattan properties have been issued. Conventional wisdom holds that fewer sources of funding will ultimately lead to higher debt cost and lower commercial real estate prices.

“Spreads have widened out. If your debt is more costly it will affect the pricing of equity,” said John Kukral, CEO of Northwood Investors and former head of real estate at the Blackstone Group, speaking generally.

Still, observers argue that the impact on Manhattan real estate will likely be limited, provided other sources of financing are still available. Most major commercial real estate loans in New York City are issued by balance-sheet lenders, such as insurance companies or banks, according to Gaines. Eyzenberg echoed the point: “It’ll affect maybe a small portion of market but for the most part the New York City market will be unaffected.”