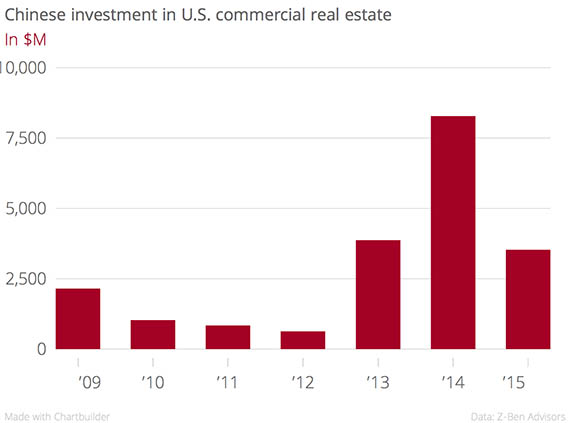

From the New York website: In a single weekend, Anbang Insurance Group laid out $19.3 billion in cash to acquire two marquee U.S. hotel portfolios, an enormous sum that roughly represents the total volume of Chinese investment in U.S. commercial real estate from 2007 to 2015.

On Sunday, the business world was buzzing about the Beijing-based insurer’s deal to buy the 16-property Strategic Hotels & Resorts portfolio from the Blackstone Group for a record $6.5 billion. Just hours later, the Associated Press reported that a consortium led by Anbang was the mystery bidder behind the $12.8 billion cash offer for hotel real estate investment trust Starwood Hotels & Resorts.

Anbang’s play comes as industry leaders voice concern that Chinese investment in U.S. commercial assets has reached a peak. If both deals close (which is far from certain in the case of Starwood), Anbang will have spent close to 10 times the total it paid Blackstone for the Waldorf Astoria hotel a year ago.

In the case of the Strategic Hotels properties, Anbang is reportedly paying an 8 percent markup on the $6 billion Blackstone — a frequent trade partner — paid for the hotel chain just three months ago. In the case of Starwood, Anbang is offering almost 20 percent more per share than Marriott offered last year as part of a takeover bid that was accepted by Starwood. If its bid is successful, Anbang will also have to pay a hefty break-up fee to Marriott. These kinds of rapid price increases are hardly unusual in boom times. But confidence in the U.S. commercial real estate market has softened noticeably since Blackstone bought Strategic Hotels and Marriott agreed to take over Starwood.

The moves also appear to run counter to Anbang’s stated investment strategy of finding assets below book value and with an expected return on equity above 10 percent. According to a Thomson Reuters estimate cited in the New York Times, the company’s offering price on the Starwood portfolio doesn’t reach a 5 percent earnings yield through 2018.

So why exactly is Anbang so keen on buying U.S. hotel properties? Here are four likely reasons:

I. Global ambitions

Anbang, which began a little over a decade ago as a regional car insurer, has grown rapidly over the past two years, largely by selling high-yield investment products (along with insurance) to Chinese savers. The company’s assets under management grew almost seven-fold from January 2014 to September 2015, to $127.5 billion, according to the Wall Street Journal. All that money needs to be invested, preferably in short order, and buying real estate in bulk is a convenient way of achieving that end. When it bought the Waldorf Astoria, Anbang said it would be actively seeking North American assets with stable investment returns.

Foreign assets hold a special strategic appeal to Anbang, according to Evia Liu, an analyst at Z-Ben Advisors. The insurer harbors ambitions of becoming a global, diversified financial conglomerate, Liu said, and has been swallowing up foreign insurance companies such as Fidelity & Guaranty Life in the U.S. and Tong Yang Life in South Korea. Buying two prestigious U.S. hotel collections is a further step in that direction, while also diversifying its holdings. It also raises the firm’s profile within China. “These kinds of activities give Anbang a good branding,” argued Liu, adding that owning name-brand assets could make it easier to win over additional customers in the future.

Credit: The Real Deal

II. Low returns in China

Beijing has long prevented capital from freely leaving the country. As a result, asset prices within China are considered inflated and returns depressed. The current economic slowdown only aggravates the problem. For institutions like Anbang, this means finding profitable investments in China is far more difficult than abroad. And because investment yields in China are low, Chinese institutions tend to have both a lower cost of capital and lower return expectations than their U.S. peers, making it easier to outbid them.

“Because China has excess capacity in so many sectors, there are diminished investment opportunities in China,” said David Dollar, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and former U.S. Treasury emissary to China. “Hence it is natural for Chinese firms to look more to investment opportunities abroad.”

III. The dollar

The dollar has been slowly appreciating against the Chinese yuan since August, when Beijing suddenly devalued its currency. But many analysts believe the yuan still has a ways to fall, creating an incentive for Chinese institutions that make most of their revenue in Chinese currency to invest in dollar-denominated assets.

“I don’t think Chinese institutions want to slow down. It has a lot to do with FOREX (foreign exchange) expectations,” said John Liang, executive vice president at Chinese development firm Xinyuan Real Estate. “High-quality, dollar denominated U.S. assets are very attractive to Chinese institutions in the near-to-mid term.”

Here’s a scenario: Say you’re a Chinese insurance company and you want to buy a U.S. office building, hold it for five years and then sell it. You’re in a bidding war with U.S. investment funds, and everyone expects the asset to hit an annual return of 7 percent. But being from China, you have an ace up your sleeve. Analysts expect the dollar to rise – let’s say by an annual average of 3 percent over the coming five years. Because your liabilities are yuan-denominated (i.e. savers bought your insurance policies in yuan and expect payouts in yuan as well), you get to benefit from that appreciation. That means if you buy the hotel, your return will actually be 7 percent plus 3 percent, or 10 percent per year. This potential for added return, along with your lower cost of capital, means you can comfortably outbid U.S. competitors.

IV. Friends in high places

All Chinese institutions have a strong incentive to invest abroad. But in a country where the central government still largely controls the flow of capital, few get to do so as freely as Anbang. Observers speculate this could have something to do with political connections. According to news reports, Anbang’s CEO Wu Xiaohui has close ties to China’s ruling elite.

“We know from our previous meetings that they still have pretty good connections with the party,” said Pedro Goncalves, an analyst at Z-Ben Advisors. He contrasted Anbang with Fosun International, a Chinese investment giant that owns 28 Liberty, a Lower Manhattan office skyscraper, but is less active in the U.S. than Anbang. “The main shareholder of Fosun has a strong presence in China but does not have such good relations with the party,” Goncalves said.