A new study claims Related Companies’ massive Hudson Yards project will contribute $25.6 billion to New York’s gross domestic product during construction, and another $18.9 billion annually after completion. That’s bigger than the GDP of Iceland!

A new study claims Related Companies’ massive Hudson Yards project will contribute $25.6 billion to New York’s gross domestic product during construction, and another $18.9 billion annually after completion. That’s bigger than the GDP of Iceland!

But the report, commissioned by Related, authored by consultancy Appleseed and published Monday under the title “An Investment That’s Paying Off,” leaves a number of questions left unanswered. Here are three of the biggest:

1. No vacancy: The report claims that once completed, Hudson Yards will generate (directly and indirectly) more than $42.1 billion in annual output. Of that, $18.9 billion will be a net contribution to GDP (i.e. Hudson Yards’ output minus its input costs). But that’s based on the assumption that its office vacancy rate will be merely 5 percent. Is that realistic?

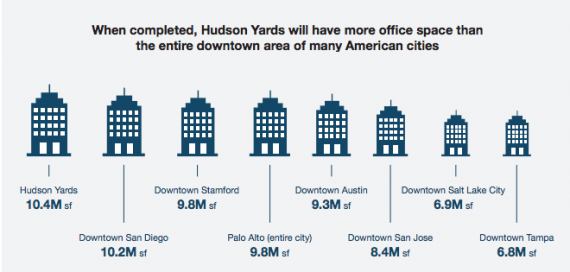

Hudson Yards will have 10.4 million square feet of new office space when completed (Credit: Appleseed, “An Investment That’s Paying Off”)

Midtown’s office availability rate stood at 10.6 percent in the first quarter, according to Colliers International, and signs point to a softening market. Adding millions of square feet of office space at Hudson Yards should push up vacancy rates in the medium run. And historically, most giant office projects like the Empire State Building or the World Trade Center struggled with high vacancy rates after completion. Besides, if there is near-limitless demand for expensive new office space, why is Silverstein Properties struggling to fill 2 World Trade Center?

Related’s Michael Samuelian argues that Hudson Yards is simply a better product, and that the fact that its first two office towers are virtually leased up means subsequent towers will likely also be fully leased. That’s possible, but there is no guarantee that will happen, and assuming a 5 percent vacancy rate in the face of far less rosy real-world numbers seems suspect.

2. Moving Peter to pay Paul: Even if all Hudson Yards towers are fully leased, many of those tenants have come and will continue to come from Midtown. What is $42.1 billion in output worth if it’s merely shifted over from other parts of the city? If businesses that directly and indirectly generate $42.1 billion worth of annual output leave Midtown and relocate to Hudson Yards, for example, the net benefit to the city is… $0.

The report’s authors recognize this and concede that Hudson Yard’s net benefit to the city will be smaller than $42.1 billion at first. Still, given the demand for new space amid Manhattan’s aging office stock, Appleseed’s president Hugh O’Neil argued that “it doesn’t take long before all that office space becomes totally a net addition to city’s economy.” And Samuelian pointed to a 2013 report by the Independent Budget Office, which argued that New York will need to add 52 million square feet of office space by 2040 to meet demand.

The logic holds that in the long run, having more high-quality office space makes it more likely that companies move to New York and existing ones stay. But how long of a run are we talking? Is it really likely that Hudson Yards will add much to the city’s output in its first decade after completion? The report doesn’t address these concerns.

3. Opportunity cost: The report claims that Hudson Yards will contribute $1.78 billion to the MTA’s coffers during construction through ground lease payments and air rights purchases, and another $89 million annually after completion. But it’s not as if the MTA’s only choice was between leasing the land to Related et al. and letting it sit empty and making no money from it. The MTA could have done other things with the land (though it’s also true that no one else put forth a viable alternative). To truly gauge Hudson Yards’ benefit to the MTA, one would need to subtract the opportunity cost of not pursuing alternative uses.

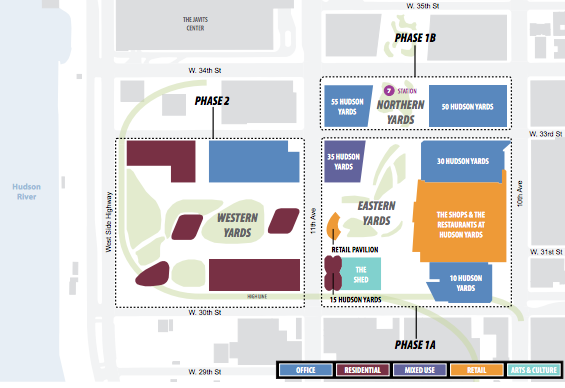

Hudson Yards project components (Credit: Appleseed, “An Investment That’s Paying Off”)

Appleseed’s generally well-researched report makes the case that spending all that money on Hudson Yards will have a big economic impact – which should be beyond dispute.

But it doesn’t attempt to answer the truly important question: what exactly the development’s net economic benefit to the city will be one year, five years or 10 years after completion? Casual readers may get the impression that it does, however. Deputy Mayor Alicia Glen certainly appears to have understood it that way, saying in a statement that the report is a “clear affirmation that the city’s infrastructure investment was a wise one.”