TRD Special Report: Boaz Gilad remembers first meeting Gal Amit and Rafael Lipa around 2008, when the U.S. economy was on its knees and Gilad’s firm, Brookland Capital, “didn’t have money to buy a cup of coffee” — much less finance the sort of ground-up projects that have since made it one of Brooklyn’s busiest condominium developers.

At the time, Amit and Lipa were working with Brooklyn real estate investor Abraham Leser on an unprecedented deal: taking him to Israel, where a new entity holding some of Leser’s New York properties would issue publicly-traded bonds on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange (TASE).

“To their credit, they kept in touch with us,” Gilad said of Amit and Lipa. In 2014, with local real estate values catching up to their pre-recession peaks, Brookland went to them to do an Israeli bond deal of their own, raising roughly $35 million.

On the same day, Extell Development’s Gary Barnett raised about $300 million through a bond offering backed by the firm’s enviable portfolio of Manhattan properties. A lot more people started paying attention to the land of milk, honey, and now, capital.

For small-to-mid-sized players, the Israeli bond market allows them to raise corporate-grade debt that they couldn’t score back home. For the bigger firms, it’s a way to do it at a healthy discount to what domestic lenders would offer on mezzanine financing. Since 2008, U.S. developers and landlords have raised over $2.5 billion on the Israeli bond market, according to TASE data cited by Bloomberg. A good chunk of them have holdings in New York, which is perceived as about as safe a bet as they come by Israeli investors and regulators.

But what exactly does raising money in Israel entail? Despite several articles depicting Israel’s debt markets as one of several notable trends in real estate financing – like EB-5 or crowdfunding – there’s been little examination of the dance a U.S. builder must do to tap that capital.

Any company looking to issue bonds in Israel has to navigate a maze of regulatory procedures before making its debt offering, which entails becoming a publicly traded entity on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange. Indeed, an Israeli bond issuance is in fact an initial public offering — except it is debt being offered to investors, instead of equity.

This means your average player can’t simply parachute into Tel Aviv, sign some papers and walk away with funds.

No, an Israeli debt issuance is a months-long tango involving a host of financial advisors, lawyers, accountants, underwriters, credit ratings authorities and government regulators. For American developers and landlords, it requires patience and a willingness to open up to Israel’s sophisticated financial markets.

And most importantly, it requires the real estate.

‘Cherry picking’ a portfolio

Most Israeli bond issuances by American property firms have involved one of a handful of boutique consultancies that have cornered the market.

Yehonatan Cohen

Like Amit and Lipa’s Victory Consulting, Tel Aviv-based advisory firm InFin — led by Yehonatan Cohen and Yossi Levi, alumni of Israeli financial conglomerate Clal – has guided firms including the Related Companies, the Klein Group and Delshah Capital.

Others, like Extell, opted to work directly with Israeli underwriting firms like Apex Issuances, which in addition to its role as an underwriter, offers advisory services to U.S. clients.

These consultants shepherd the entire issuance through; Victory and InFin, for example, have relationships with Israeli financial firms like Apex, Poalim IBI and Clal that underwrite the bonds, as well as contacts at white-shoe law and accounting firms fluent in Israel’s regulatory requirements.

“Before we do everything, we try to be in a position where we see the end of the deal before we start,” Amit said. “In order not to waste money, you need someone that knows all the moving parts, who can see the end at the beginning.”

[vision_pullquote style=”1″ align=””] “In order not to waste money, you need someone that knows all the moving parts, who can see the end at the beginning.” — Gal Amit [/vision_pullquote]

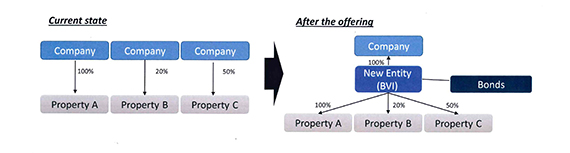

First, and arguably most important, is “cherry-picking, together with the clients, the most suitable package for the Israeli bond market,” said Levi. It is this portfolio, which lumps a U.S. developer or landlord’s assets within an offshore entity, usually in the British Virgin Islands, that backs the bonds issued on the TASE.

“You put everything on the table and say, ‘This is what I have and what I don’t have,’” Gilad said. “They [the consultants] are the ones who are positioning the situation and telling the [company’s] story.”

Unlike in the U.S., where investors typically fund deals on a per-property basis, this model enables companies to borrow against a larger pool of assets. It creates a corporate entity with multiple holdings and its own balance sheet, spreading risk and enabling firms to raise debt at remarkably low interest rates — established developers with solid credit can sell bonds for 5 to 7 percent, about half what they’d pay for mezzanine debt back home.

“If you look at the interest rate that these companies place compared to the cost of mezzanine loans, you see why they come to Israel,” said Ofer Amir, head of the Israeli real estate division at credit ratings agency S&P Maalot. “It’s not the Israeli or Jewish connection; it’s the money.”

To obtain those low rates, a firm needs to secure a good credit rating from one or both of the two major Israeli ratings agencies – S&P Maalot, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Standard & Poor’s, and Midroog, an affiliate of Moody’s.

[vision_pullquote style=”1″ align=”right”]“It’s not the Israeli or Jewish connection; it’s the money.” — Ofer Amir [/vision_pullquote]

“In order to get a decent rating, you need a major portion of income-producing assets [in the portfolio] that can produce cash and maintain a decent cash ratio that can support the rating,” said Cohen.

This makes multifamily rental housing the most attractive asset for piecing together an Israeli bond deal – “Stuff has to happen in order for it not to yield,” as InFin’s Levi put it — followed by retail properties and other cash-generating holdings like hotels and office buildings. Bondholders view a steady stream of income into the entity they are investing in as evidence of that entity’s ability to repay debt.

Jacob Klein

“They cherish very highly strong cash-generating assets, because those are the foundation to service the bond debt,” said Klein Group president Jacob Klein, whose retail-focused firm sealed a $55 million offering in November. “That’s basically how we built our offering.”

Simplicity is also a virtue; one New York developer who successfully issued bonds in Israel said his issuing portfolio leaned toward assets “with a clean ownership structure.”

“Anything where we owned [a significant majority interest] and was a cash-flowing asset went in,” the developer said.

Meanwhile, condominiums and development sites — particularly sites “built to sell,” as several sources put it — are seen as riskier bets than cash-producing assets like rental housing, retail properties and hotels, and can hurt a company’s bond rating and the rate it can secure on the debt raised.

Ori Eisenberg, a partner at advisory firm One Ha’am who advised the Moinian Group on its record-setting $361 million issuance last May, said offerings backed by condo assets don’t have the same appeal because bondholders don’t get to profit from the upside.

“I think if you [a condo developer] are ready to pay a higher coupon,” he said, “maybe then the market will be open for you.”

There’s certainly evidence of a lukewarm reception to bonds backed by condo projects and development sites. Extell, in particular, saw its bonds take a hit, with Israeli investors concerned about a softening New York luxury market and potential oversupply on the high end.

Gary Barnett

This prompted Barnett to visit Israel in March to try and reassure investors, and to host them in New York to “take them through our properties and to show them the quality and the strength of the assets,” he told Bloomberg at the time. Representatives for Extell didn’t respond to requests for comment.

To make a portfolio more attractive to Israeli investors, condo developers often sprinkle in some cash-flow assets. “The reason [Extell’s offering] succeeded,” Eisenberg said, “is that they included income-producing assets,” such as the firm’s W Hotel Times Square.

Brookland’s Gilad didn’t have that option — his firm exclusively handles condo development and conversion projects. The firm’s successful issuance, he said, was in part due to “the story we designed” for investors, which portrayed the developer’s sheer volume of business as a safeguard against risk.

“We finish a project every month-and-a-half,” Gilad said. “Even though we’re a development company, we have cash flow like [a landlord].”

The consultants also must understand everything from the company’s business profile and leadership to in-depth financial and market analysis of the assets it hopes to include in the deal.

“We’re building a simulating model that analyzes the portfolio – what the financial statements will look like, what will be the rating, the expectation about the interest rates,” InFin’s Levi said of the process. “We’re not motivated to take companies that we don’t believe are going to make it.”

[vision_pullquote style=”1″ align=””] “We’re not motivated to take companies that we don’t believe are going to make it.” — Yossi Levi [/vision_pullquote]

Advisors are rewarded handsomely for their efforts, with commissions — depending on the size of the raise — ranging from 2 to 3 percent of the total issuance. All the legal, accounting and appraisal fees combined can range between $500,000 to $1 million, and there is also the cost of flying to and staying in Israel (more on that later).

But all that money is in service of the belief a company’s initial public bond offering will be just that: the first play in a long-term relationship with the Israeli market, with each series of bonds issued helping pay the last series off, and hopefully then some.

“If you think you’re going to raise only one round of bonds,” Gilad said, “it’s a complete waste of money.”

Opening up the books

[vision_pullquote style=”1″ align=”right”]“If you think you’re going to raise only one round of bonds, it’s a complete waste of money.” – Boaz Gilad [/vision_pullquote]

Heading to the Israeli bond markets opens firms up to a level of scrutiny they may not be accustomed to.

Most Israeli bond offering deals are audited by the usual suspects – the likes of Deloitte, Ernst & Young, PricewaterhouseCoopers and BDO. Since nearly all U.S. real estate firms that have successfully issued bonds in Israel are private companies in the U.S., the auditors have their work cut out for them.

“Some of [the companies] don’t have audited financial statements, because they don’t need to have audited financial statements,” said Amitay Weber, an audit partner for Deloitte in Tel Aviv. “We have to guide them from an accounting and bookkeeping perspective through the process.”

Amitay Weber

“It’s a big transformation when you go from being a private company to going public,” said Klein. “It doesn’t matter whether you go public in Israel or America or anywhere else – the level of scrutiny and due diligence is very similar.”

The audit also involves converting a company’s financials from the generally accepted accounting principles, or US GAAP, into the International Financial Reporting Standards, or IFRS, a standardized global system that Israel adopted in 2008.

And in a more rigorous version of the work done by the issuing company’s advisors, the accountants pore through company records – everything from background checks on the principals and shareholders to analyzing the financials of the assets.

All this work leads to Exhibit A — the prospectus. As with U.S. firms looking to go public on the New York Stock Exchange, this is the regulatory document that spells out the product being offered to investors: the organization, the assets it holds, the scope of its debt issuance and what it seeks to use the funds for.

Enter the lawyers. While the prospectus is a financial document touting the issuing company to potential investors, it’s also a legal document to be filed with the Israel Securities Authority – Israel’s version of the SEC – and scrutinized by ISA regulators.

Dudi Berland

“I have a team of seven people staying from day to night, reading documents,” said Dudi Berland, a partner at Israeli law firm Shimonov & Co. “We study and understand how the company works in terms of its loan documents, its partnership agreements. It’s due diligence; you take a company and you have to understand its characteristics.”

For private firms not used to having to keep audited, regularly updated financial records, it can be a strenuous process that can take upwards of two months.

“Creating three years of audited financial statements and approvals was a fair amount of work,” one New York developer said. “Everyone was working pretty late.”

New York values

The window for filing a prospectus comes up four times a year – within 90 days after the completion of the fiscal quarter in Israel. Once filed, the company will set up a meeting at ISA headquarters in Jerusalem that, by numerous accounts, can involve up to two dozen attendees from both sides: the issuing entity’s principals, advisors, underwriters, lawyers and accountants on one side, and Israeli regulators on the other.

Depending on the company and the nature of its prospectus, the meeting can range from a few hours to nearly the entire day, but its purpose is always the same: taking the initial prospectus and ensuring that the entity seeking to issue bonds in Israel has covered all its bases. While much of the conversation is conducted in Hebrew, and most of the questions handled by the company’s posse of advisors and consultants, developers get a chance to directly respond to questions in English.

The meeting kicks off weeks of correspondence between the company and Israeli regulators, with the aim of ensuring Israeli investors will know everything they need to about the company they’ll be investing in.

But the ISA mostly cares about whether the disclosure requirements have been met. As one source put it, regulators don’t usually “criticize the company itself.”

“They go through your prospectus, page by page, and have comments on practically every page,” said Klein. “They want more clarity, they want to understand better why this asset here is a 7-cap and the other is a 5-cap. They only look at it from the perspective of how to protect the public and the investors. I thought it was fair.”

The ISA declined to comment for this story.

In the meantime, the drafting of the prospectus also means authorities at S&P Maalot and Midroog – by now generally clued in on the issuing company and its portfolio – officially kick off their deliberations.

Ofer Amir

Ratings authorities get to work examining both the assets in the portfolio and “at the whole picture” of the issuing company, said S&P Maalot’s Amir. That includes visiting the U.S. to meet corporate principals, see the real estate assets in the portfolio first-hand and familiarize themselves with the firm’s other holdings.

“It’s important to understand the other operations the company has, what other kinds of assets it owns,” Amir said, citing Related’s $210 million bond issuance in 2015 as an example. “They just took a few of their assets into their portfolio. [Related is a] multibillion-dollar operation, so it was really important to understand the rest of the company and understand the overall strategy.”

The ratings agencies also build cash-flow models that simulate, via “stress tests,” whether a company’s assets will generate enough income to repay investors. But one developer said he found those stress tests failed to account for areas with yet-untapped upside, such as emerging retail destinations.

In any case, the rating a company receives on its portfolio helps determine the interest rate it’ll be able to secure on the bonds it will issue. But as Eliav Bar-David, the CEO of Israeli underwriter Apex Issuances, noted, “there can be two companies with the same rating and different rates” on their respective debt offerings, because of variables such as investor sentiment and company pedigree.

As the prospectus undergoes several revisions – usually around four drafts – the ratings agencies are right there, monitoring changes that may affect the rating on the portfolio. But U.S. real estate companies have three significant trump cards over other foreign and even Israeli firms: location, location, and location.

“When we deal with U.S. issuances, we start from a very good level of country risk – the lowest, according to S&P,” Amir said. “We see the New York market, and especially the residential market, as very strong and very stable.”

[vision_pullquote style=”1″ align=”right”] “You’re now a regulated company; who you are is in the public domain.” — Louis Tuchman [/vision_pullquote]

Of course, being under the microscope for this long can often be too much to take for a New York investor used to operating in the shadows. Besides not having the right mix of properties for a bond offering, it is the process of becoming a public entity that drives many prospective issuers away.

“You’re now a regulated company; who you are is in the public domain,” said Louis Tuchman, co-chair of the tax department at New York-based law firm Herrick Feinstein, who has worked on Israeli bond offerings in the past.

“Real estate people run the gamut — some of them love publicity, some of them shun publicity, some of them have litigious pasts,” Tuchman said. “I think there are people who look at that and say, ‘I’m a wealthy guy and a private guy, I don’t want to do all that.”

On the road

Once the prospectus is made public, it’s time for the speed dating referred to as “the roadshow.”

Over the course of an intense fortnight, the principals of the issuing company fly to Israel and hold upwards of 40 meetings with insurers, pension funds, mutual funds and high-net-worth individuals to gauge investor interest in the company drum up demand for the securities it is issuing.

Eliav Bar-David

It’s a grueling trip — one developer described a three-week-long roadshow featuring four to five meetings daily, and spoke of how tricky it was to juggle that schedule with tending to his business in New York. (“The food is absolutely fantastic,” he said of Tel Aviv.)

But the roadshow is crucial as it lets the offering company negotiate its covenants with bondholders. These can range from the minimum equity included in the portfolio, to the leverage ratios on the portfolio’s “balance sheet,” to net operating income on the assets.

“Since those bonds are [usually] unsecured, the only thing that protects investors are the covenants,” said Infin’s Levi. “Doing the roadshow, we get feedback from investors on the terms of the deed of trust.” The issuing entity’s accountants and lawyers take all that in and make the necessary tweaks to the prospectus.

“Each investment house sends their requests to the issuer and the underwriter, and they all aggregate all the requests from the potential investors,” said Eli Levi of Israeli investment firm MORE, which manages more than $2.5 billion in funds and is an active player on the Israeli bond market. “You [try to] limit the company’s leverage, [establish] minimum equity, but also how much risk in terms of development they’re going to do in the future.”

These covenants aren’t strictly financial. Gilad noted how Brookland’s covenants with its investors bind the firm – which poured all its real estate holdings, including future projects, into its issuing offshore entity – exclusively to residential development in Brooklyn.

According to sources, one of the reasons Moinian was able to secure a 4.2 percent interest rate — a record low rate for a U.S. developer at the time — is that the covenants placed heavier restrictions on how he could use the funds.

“The negotiations are money time,” Gilad said. “Before you go public, the advisors and investment bankers are on the phone [constantly]. They’re calling me asking, ‘Are you willing to give this or that?’ So when you go public, the suit is basically tailored. But that doesn’t mean they’re going to buy it.”

[vision_pullquote style=”1″ align=””] “We thought it would be difficult to explain how unique the Soho retail market is… [Israeli investors] were very well informed. We didn’t shock them with anything.” — Jacob Klein [/vision_pullquote]

The roadshow can sometimes trip up the biggest of players. Jeff Sutton’s Wharton Properties, for example, attempted a record $500 million issuance last year, but the deal fizzled out due to its complexity.

Despite receiving a favorable rating on a portfolio that featured prime Manhattan retail assets, investors balked at Sutton’s desire to use the proceeds to issue debt of his own, according to Israeli market sources. As one put it, Israeli investors “want to invest in real estate, not structured finance.” New Jersey-based Treetop Development’s attempt to raise $30 million also didn’t pan out due to unfavorable ratings, while Michael Stern’s JDS Development Group went through the roadshow, but decided not to go through with the issuance after a tepid reception from Israeli investors.

While doing his firm’s roadshow, Klein was struck by how well Israeli investors understood New York real estate.

“We thought it would be difficult to explain how unique the Soho retail market is,” he recalled. “I thought I’d have to get into great detail to explain what it is. They were very well informed. We didn’t shock them with anything.”

The home stretch

After the roadshow, the prospectus is sent to the ISA for regulatory approval. In the lead-up to the bond issuance, the entity receives its final ratings from S&P Maalot and Midroog. It is common practice for the company to proceed with the ratings agency that gives it the better rating — which could create an incentive for the agencies to play ball.

Then it’s time for the actual bond offering, which comes in two phases. First, an institutional tender is opened just to accredited investors, many of whom have already got to know the company through its roadshow.

Michael Shah

The institutional tender represents a majority of the total debt issuance – up to 80 percent of the maximum amount raised. East Village-based developer and investor Delshah Capital, for instance, raised $80 million of its $102 million January bond offering through this opening phase.

For Israeli institutional investors, the bonds being offered by U.S. firms can hold tremendous appeal. Investment opportunities in Israel can be somewhat limited, particularly for funds awash with liquidity thanks to regulations that see the average citizen contribute a sizable chunk of their salary to pension funds and other long-term savings vehicles.

The most active players on the Israeli bond market are mutual funds, according to Apex’s Bar-David, “because they’re able to invest only in Israel, so they don’t have any way to diversify their portfolio.”

Pension funds and insurance companies, meanwhile, may invest abroad, but they are also active in the Israeli bond market. Private equity firms and hedge funds tend to stay away — the returns on publicly traded bonds aren’t usually fat enough for them.

Within days of the institutional tender comes the second phase, the public tender – open to the general public as securities offered on the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange. The issuing company has, through a portfolio of assets bundled and securitized via Israel’s public bond market, become a publicly traded entity in Israel.

But it took a long, cumbersome process that isn’t for everyone. Ariel Property Advisors founder Shimon Shkury, who advised several New York-based firms on the Israeli market, believes a company should have “a minimum of $100 million worth of equity,” as well as the cash flow to cover the debt service required, before entertaining a Tel Aviv bond deal.

“When I present with companies,” Shkury said, “I’m saying, ‘Look, we need to do a lot of work before we know you’re a viable candidate, and you have to do a lot of work and spend a lot of money.’”

And once you’re officially a public entity in Israel, a bond deal isn’t a one-off. You’ve gone public, and that isn’t changing — you’ll be subject to ISA regulatory requirements and the covenants of your agreement with your bondholders. Leser, who did the first ever U.S. bond deal in Israel in 2008, is on his fifth raise, while Joel Wiener’s Pinnacle Group, Yoel Goldman’s All-Year Management and Joel Gluck’s Spencer Equity Group have raised multiple series.

Of course, being public also means being subject to macroeconomic forces. “When the ruble collapsed, my bonds dropped like crazy,” Gilad said, citing how the Israeli market conflated the declining Russian currency’s threat to high-priced Manhattan condos with the more modestly-priced product that Brookland offers to local homebuyers in Brooklyn.

From left: Assaf Fitoussi and Boaz Gilad of Brookland Capital

“I have nothing to do with the Russian market and Russian buyers; my [buyers] are not Russian,” he added. “I’m speaking monthly with investors over the phone and I say: ‘We’re middle-class, we’re Brooklyn. Me and Moinian and Extell are completely different companies.’”

And though Extell has had to deal with some hiccups on the Israeli bond market, it’s the case of Urbancorp that really has investors skittish.

One of Canada’s largest residential condo developers, Urbancorp raised nearly $48 million through an Israeli bond issuance in late 2015. But in April, the bonds plummeted after the company announced a delay in 2015 results and the resignation of its legal advisers. Trading was halted, and bondholders are pushing for immediate repayment of their money.

“Urbancorp is an exceptional case and doesn’t represent the norm but as a result we are likely to see Israeli investors be more skeptical about future debt offerings by foreign real estate companies,” Ilan Azoulay, chief investment manager at Tel Aviv-based Epsilon Investment House, told Bloomberg in April.

Israeli market sources who spoke for this article widely echoed that sentiment, saying the Urbancorp debacle would likely make the market more “selective” toward future offerings by foreign real estate players. One described the Urbancorp situation as “borderline fraud.”

But the story of Israel’s corporate bond market has been a mostly successful one, as far as U.S. developers are concerned. Gilad said one of the perks of his company’s going public in Israel was the corporate infrastructure it established – one that serves him well in his U.S. dealings, particularly with private equity investors who are more comfortable dealing with a transparent, public entity.

“Having a board, having a rating, having audited financials – I’m so happy I did it, regardless of the bond money,” he said. “It brings a lot of comfort to [an investor] who says, ‘I’m not the only one who’s going to be checking on my money.’”