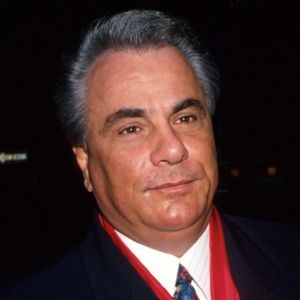

Six-foot-three, mustachioed and built like a bouncer, Gary LaBarbera commands attention. And that’s before he even opens his mouth.

Drop him in a sea of hardhats and he channels his bellowing voice like a fog horn.

“Let City Hall hear you, let the City Council hear you, let ‘em hear you!, let ‘em hear you louder,” he hollered at a Lower Manhattan rally in December, and the crowd roared back at him. Delegates marched hoisting makeshift coffins, calling attention to the number of nonunion workers who’ve died in construction-related accidents.

Even for a labor force with a flair for the dramatic — the unions’ inflatable rats are ubiquitous outside buildings owned by those who haven’t shown solidarity — it was an especially theatrical presentation. And LaBarbera, president of the Building and Construction Trades Council of Greater New York, steward of 15 national and international unions representing 100,000 workers, appeared in his element.

“Having that many people, you actually feel the energy from them,” he told The Real Deal in a recent interview. “It takes on a life of its own. I never have any prepared remarks. I never read from notes. It all comes from my heart.”

To watch him perform atop his soapbox, one might think LaBarbera is the give-no-quarter sort.

In reality, however, his job depends on bringing together real estate stakeholders who are often diametrically opposed foes.

“I can be in a room with the leaders of this industry and have a serious, intellectual conversation, or I can be in front of 20,000 people rallying them up,” he said. “That’s something I pride myself on.”

But the challenges of LaBarbera’s position have never been more acute than over the past year. He failed to broker a deal on the 421a tax abatement renewal between the construction unions and the Real Estate Board of New York, which speaks for developers.

The death of the abatement brought with it, at least according to developers, any chance of building rental housing in New York. The issue, they say, is particularly critical in the outer boroughs, where market rents often don’t cover the high price of land acquisition and construction costs.

To resurrect the program would require REBNY and Building Trades to agree on wage requirements for construction workers at 421a sites. Those requirements would mean developers would have to pay union wages on all 421a sites, a provision most of them argue would eat up all their profits.[vision_pullquote style=”3″ align=”right”] “He can try to push them in a direction, but it’s ultimately not his decision.” [/vision_pullquote]

Privately, some of the city’s top developers think LaBarbera is a man who understands nuance and genuinely looks to find common ground between the two sides.

But they say also he faces a fundamental problem: An unruly constituency in the form of bull-headed individual union leaders and an inability, as a go-between with no concrete power, to hammer them into submission.

“Gary, who I consider a friend, deep down believes in his heart in the positive things that unions can bring to the table,” said one major developer, who had knowledge of the negotiations. “But the reality right now is that Gary’s job is to coordinate with all of these different unions but he doesn’t individually control any of them. He can try to push them in a direction, but it’s ultimately not his decision.”

Cuomo in his corner

Gov. Andrew Cuomo

The clock officially ran out on 421a in January. But until recently, developers hoped it could be renewed before June 16, the last day of the current Albany legislative session.

Just how the high stakes are was perhaps best captured by a March encounter at a REBNY meeting between Related Companies chairman Stephen Ross and Tishman Speyer CEO Rob Speyer, two of the industry’s most powerful players.

Speyer, according to Crain’s, wanted to rekindle talks with the unions — something Ross, who owns the Miami Dolphins, objected to. The two got into a heated argument and reportedly nearly came to blows.

“This isn’t the NFL,” Speyer yelled. “I’m not going to be pushed around.”

The drama over the abatement has also added fuel to the ongoing feud between Gov. Andrew Cuomo and Mayor Bill de Blasio. De Blasio needs 421a to fulfill his core promise of creating and preserving 200,000 affordable housing units in the city over the next decade. Alicia Glen, his deputy mayor for housing, has said the need for new affordable housing trumps the need to employ union workers. But Cuomo has made his allegiances clear.

“I will not sign a bill that is not accepted as a fair deal by organized labor and the Building Trades … period,” he said, speaking at an April meeting of North American Building Trades in Washington, D.C.

Renewing the program without a prevailing wage stipulation would hurt union market share in New York, Cuomo said.

“There are forces that want that program to be open-shop because if in New York State, which is a bastion of labor support, if you can get a New York City construction project that is government-subsidized to be open-shop, then you have really diminished labor,” he said. “And if you can do that in New York, it is a national statement that union labor is not what union labor once was. That’s what’s going on.”

A spokesperson for the governor did not return multiple requests for comment.

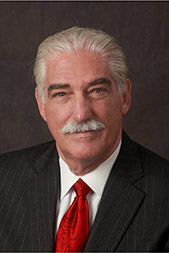

John Banks, president of REBNY

LaBarbera sees Cuomo’s public statements on the matter as his ultimate leverage.

“I believe the word he said was ‘period,’” LaBarbera told TRD. “He’s put a flag in the ground on this one. To me, this is a fait accompli. If we don’t come to an agreement, it’s not beyond the pale to think that Cuomo and the legislature will just say: ‘This is what we’re going to do.’”

But some in the development community see Cuomo’s ringing endorsement of the unions as a curse in disguise for LaBarbera. Any progress LaBarbera had made in bringing the unions closer to a middle ground, they said, would be erased by the governor’s remarks.

“You rally your group to a position and it’s hard to walk back from that position,” said a person with knowledge of the negotiations. “The governor saying that has created a dynamic where Gary will have to fight towards an unrealistic goal.”

The United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners and the International Union of Operating Engineers are widely regarded as the most difficult with which to negotiate, sources said. The IUOE, in particular, holds sway because its workers are so specialized – they can make or break a project.[vision_pullquote style=”3″ align=”right”] “He’s put a flag in the ground on this one. To me, this is a fait accompli.” [/vision_pullquote]

And they may feel invincible with Cuomo as their cornerman — try as LaBarbera might to convince them that it’s worth compromising to get work.

“There’s a rational underpinning to what Gary says,” said MaryAnne Gilmartin, CEO of development firm Forest City Ratner. “It doesn’t mean everyone around him is rational.”

Some developers say their projects are simply unfeasible without 421a and have put plans on ice.

A rendering of Durst’s Halletts Point development

The Durst Organization, for example, kicked off construction on the first building at its $1.5 billion Halletts Point residential and retail development while 421a was still in place. But successive buildings at the Queens project won’t go ahead without the program or something of its ilk, according to Jordan Barowitz, the firm’s director of external affairs.

“Without 421a, there’s no way the project is economically viable,” Barowitz said. “On building one, without 421, we’re cash-flow negative at stabilization. At 90-plus percent occupancy, the building loses money if we pay full taxes.”

And at Forest City’s Pacific Park project in Brooklyn, any affordable buildings that have yet to break ground are unlikely to rise without 421a, according to Gilmartin.

The program, she said, “is essential for the further construction of the affordable components.”

For the past several months, Forest City Ratner and its joint venture partner Greenland Group have been shopping around a “very significant” equity stake in a handful of the 15 buildings slated for Pacific Park in Brooklyn in order to capitalize their own investment in the complex.

MaryAnne Gilmartin

Indeed, Manhattan residential developers have filed far fewer applications for new residential complexes so far in 2016 than they did in the same period last year. In the first four months of the year, developers filed just 37 applications to build about 2.1 million square feet of total residential space in Manhattan, down from about 4 million square feet over the same period last year.

Only a handful of permits for large residential projects in the outer boroughs have been filed, including one for Stawski Partners’ 921-unit, 838,000-square-foot residential building in Long Island City.

LaBarbera insisted the unions have plenty of government-funded infrastructure work in the pipeline and don’t need 421a to keep their heads above water. The developers, on the other hand, are desperate for its renewal, he said.

Developers, however, point to the more than $4 million spent collectively by the Building Trades, and several other labor groups on 421a-related advertising as proof that the program is just as important to the unions as it is to them.

John Banks, president of REBNY, conceded LaBarbera is in a very difficult position.

“What’s frustrating for me is that it’s the numbers that drive the decision-making on my side of the table,” he said, referring to project costs sans 421a. “No matter how much complaining there is about what happens or doesn’t happen is not going to move the industry to build.

“In a sense, we’ve been the best friend that Gary’s had,” he continued. “But that friendship is under strain.”

One of ours

The 56-year-old LaBarbera has been a union man since the early 1980s, when he joined the International Brotherhood of Teamsters Local 282 on his native Long Island.[vision_pullquote style=”3″ align=”right”] “In a sense, we’ve been the best friend that Gary’s had. But that friendship is under strain.” [/vision_pullquote]

He carries his late father’s union initiation card in his wallet, and said childhood conversations around the kitchen table about “working people’s issues” sparked his interest in the labor movement.

His rhetoric harks back to an era when titans such as Samuel Gompers led thousands of workers in the fight to end the 60-hour workweek and the kinds of treacherous conditions that led to disasters such as the Triangle Shirtwaist factory fire of 1911, which led to the death of 146 workers.

In several conversations, LaBarbera referenced, in romantic terms, the importance of following one’s “moral compass.”

“I believed that the only real way to achieve a middle class life was to be in the union,” he said. “Everything I have in my life, I owe to the union. I raised three children — two of them went to college and one went into the Marine Corps — and I was able to give them a good, middle class life because of the union.”

“I believed that the only real way to achieve a middle class life was to be in the union,” he said. “Everything I have in my life, I owe to the union. I raised three children — two of them went to college and one went into the Marine Corps — and I was able to give them a good, middle class life because of the union.”

He worked as a forklift operator and became one of the first members of Local 282 to graduate from the Labor Studies program at Cornell University. In a union that was best-known as the fiefdom of the Gambino crime family, LaBarbera developed a reputation as “Mr. Clean.”

For well over a decade, the feds had attempted to lay the smackdown on Local 282, alleging its cement truck drivers funneled $1.2 million a year to late Gambino boss John Gotti. In 2008, the government handed down one of the largest criminal indictments ever, naming 87 individual defendants on charges that included embezzlement from the union’s health and pension funds. It was like a real-life scene from “Goodfellas.” Perpetrators had nicknames such as “Greaseball,” “Jackie the Nose” and “Fat Richie,” the New York Times reported at the time.

LaBarbera was largely credited with helping to turn around Local 282, first as court-appointed trustee in 1996 and later as its top official. He declines to talk in depth about that time of his life, but sources familiar with his role in the clean-up said he was one of the only candidates willing to take on the job, which was considered kamikaze. He and his family even received death threats from mob affiliates.

“He’s a person of faith and morals,” said Janno Lieber of Silverstein Properties. “He’s not a faker. He’s a decent person trying to represent his members to the best of his ability in a complicated situation.”

In 2009, as part of an internal dispute, LaBarbera was accused by an internal investigator of turning a blind eye to a trucking company’s effort to defraud the union. He denied the allegations. That same year, he took the helm of the Building Trades, and says he’s since struck deals for project labor agreements on $25 billion worth of private sector construction work and $15 billion worth of public work.

Developers look to his past work on overhauling the Teamsters’ benefits program as proof that LaBarbera understands the economic realities faced by today’s builders. He helped create a secondary pay rate and benefit structure that would apply to new members of the Teamsters, without requiring existing members to forego their promised benefits. The new plan resulted in the Teamsters becoming more competitive, sources said, and it’s this flexibility that developers say the construction unions should embrace now.

“Gary has a reasonable amount of credibility because he was able to reform the Teamsters,” said one developer.

The difference, though: At the Teamsters, LaBarbera called the shots. Now, he does not.

Union vs. Open Shop

LaBarbera claims the fight over 421a is about guaranteeing a fair wage for workers on sites receiving public subsidies.

But his detractors say that’s bunkum. It’s simply a tactic, they insist, to try and ensure the lion’s share of the city’s residential projects will be exclusively union. The unions, who have been losing their grip on New York over the years, are waging the 421a battle in a desperate attempt to claw back, they say.

“What do you do when you can’t fix the economic problem? You run and try to legislate it,” quipped one developer.

In the 1970s, only about 10 percent of construction work in the city was nonunion. While the numbers today are subject to much debate, industry insiders agreed that the figure now is at least four times higher.

Roughly 35 percent of all construction work in Manhattan was performed by nonunion or open-shop contractors, according to an internal report conducted by consulting firm Locker Associates for the carpenter’s union. That number shot to 61 percent for the outer boroughs.

LaBarbera claims the situation isn’t as dire as that. The unions still hold the greatest market share, and haven’t seen the same levels of attrition in government and infrastructure projects, he said.

“In this business, perception is reality. And there are those developers who want to create the perception that the New York City building trades have lost their grip and will lose their power,” he said. “That’s an inaccurate and disingenuous statement.”

He said safety is a growing concern, noting the rise of nonunion labor has brought with it a lapse in construction safety standards and a growing number of major accidents.

In November, the New York Times ran a front-page story on the surge in construction-related deaths, with the paper of record reporting that a big chunk of the fatalities occurred at nonunion job sites.

But New York developers no longer feel the same pressure to build union, sources said.

“In the old days, it was a different kind of discomfort,” Gilmartin said. “Now, it’s not brute force and intimidation. There are people that are absolutely comfortable in bucking the unions because they believe it’s their right to do so.”

The relationship between developers and organized labor began changing even more dramatically in 2011 when the so-called New York Plan — a 100-year-old agreement that required most contractors to use exclusively union labor — was allowed to expire.

It was the Building Trade Employers Association, a 1,700-strong organization headed by Louis Coletti, which called for an end to the agreement, saying it put their members at a competitive disadvantage when going up against nonunion outfits for building contracts.

Lou Coletti

In recent years, LaBarbera and Coletti, whose interests should align, have clashed over how to best deal with the unions’ declining market share. Colletti wants his constituents, who include general contractors and managers, to be able to bid on all construction projects, whether open-shop or not.

“I think he’s a terrific guy and no one has worked harder than him in trying to get his members to reduce costs to become competitive,” Coletti said of LaBarbera. “There have been some successes but not across the board. Many of my managers and general contractor members are getting out of their collective bargaining agreements and they want the freedom to win work and build it whatever way the developer wants it.”

In Colletti’s opinion, the cost of doing business exclusively the union way is becoming too high.

A NYCDCC Cement League journeyman’s hourly package, for example, is $93.00, according to the Locker Associates report. In comparison, a nonunion worker in the same position gets a considerably lower hourly wage — some less than half — making it difficult for signatory contractors to compete.

Developers told TRD that, in some instances, the benefits packages for union workers are equal to 100 percent of their base salaries.

“Our responsibility is not to pay the pension of a retired electrician in a private union,” said one developer. “The real issue here is whether there’s a path to make building union in New York economically competitive or if the unions are going to commit slow-motion suicide even as they have lots of friends in the industry who don’t want them to.”

While some unions have made moves to revise their benefits plans, others won’t budge.

LaBarbera conceded: “I don’t have the authority nor do I want necessarily the authority to instruct a union affiliate what to do and what not to do. I have to respect each of their own internal processes.”

Guinea pigs

Many New York developers, including Tishman Speyer and Related, openly talk of using nonunion labor to reduce costs — and some have drawn the ire of the unions more than others.

Related’s Stephen Ross

“To hear a developer like Steve Ross [of Related] say it’s a good thing that the city is open-shop and that costs are coming down, that’s like saying it’s a good thing that wages are coming down and workers are being exploited every day,” LaBarbera said at a Crain’s event earlier this year. “In my view, that’s the worst thing for the City of New York.”

LaBarbera and the unions have also gone after developers such as Alma Realty and the Moinian Group for using nonunion labor. But in recent years, no developer has felt their wrath more than JDS Development Group’s Michael Stern.

Whether he embraces the role or not is up for debate, but Stern has become the developer poster child for the nonunion movement.

What sets him apart is the scale and intricacy of the projects he’s trying to build with open-shop labor, particularly 111 West 57th Street, an ultra-skinny luxury condo slated to rise to a height of more than 1,400 feet.

“If they built that tower nonunion, it would be unprecedented,” Extell Development’s Gary Barnett told Crain’s last January. “More developers doing projects of that size would have to take a look at going nonunion.”

Michael Stern

Publicly, at least, LaBarbera treats Stern’s experiment with disdain.

“Where did this guy even come from?” LaBarbera told Commercial Observer last May. “The real motivator here is greed.” He has been quoted ad nauseam about so-called safety issues on Stern’s sites, and union workers routinely bring their inflatable rats when Stern makes public appearances.

It’s unclear whether LaBarbera actively encourages the protests, which are often organized by individual unions. But he’s certainly doing nothing to stop them.

“I’m agnostic on that,” he said. “I will never discourage anyone from exercising their First Amendment rights.”

But sources said LaBarbera’s bark is worse than his bite. His public posturing is a reflection of his determination to keep the city’s highest profile projects union.

Indeed, insiders said that, behind the scenes, LaBarbera has been negotiating a proposal with Stern whereby it would be economical for JDS to use exclusively union labor. The two have sat down together as recently as April to discuss, sources said.

LaBarbera declined to comment on those negotiations. Stern said only that “Gary has been a vocal advocate for his members but has always been willing to keep the lines of communication open.”

Still, not everyone appreciates the fire-and-brimstone treatment Stern has been subjected to.

“Their tactics undermine their position and their ability to build consensus,” Banks said. “It’s hard to negotiate with someone if they’ve been publicly or unfairly beating you up.”

For his part, LaBarbera admits that, when it comes to 421a, it can be difficult to always play middleman in a room full of machers.

“There’s a couple of large developers that don’t want to make a deal because they don’t want to be told what to do,” he said. “I think it’s a power struggle and an ego thing.”

As for his own ego? No such thing, he insists.

“Being fully committed to something is different from having ego,” he said. “It’s not about winning or losing. It’s about right and wrong.”