For investors in Compass, there are no shortcuts to a payday.

The brokerage is looking to raise about $50 million at a $1.3 billion valuation, which would make it the most valuable residential brokerage in the country by a distance — at least on paper. But according to the firm’s CEO Robert Reffkin, profitability isn’t a pressing goal, and investors shouldn’t expect to reap rewards anytime soon.

“They’re making an investment alongside the management team,” Reffkin said. “The luxury of our capital base is that we can think long-term.”

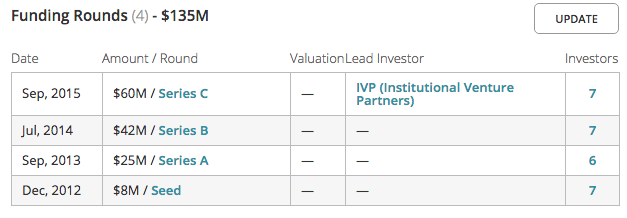

Compass strutted into New York’s residential market in 2013, vowing to transform the art of selling real estate. By deploying a $135 million venture capital-funded war chest, it expanded aggressively, bagging several firms and top agents along the way. It is now in eight regions, and in New York City, its largest market, it closed over $650 million worth of sell-side deals during a 12-month period ending Feb. 29. At some point down the road, Reffkin said, it could very well go public.

But what would investors in a Compass IPO be buying into? Critics from within the industry say it’s just a brokerage masquerading as a technology company, while admirers see it as the brokerage of the future. That’s still up for debate, but here’s what we know for sure: The firm is burning through money fast, and its numbers aren’t quite what they seem.

For example, it claims its agents generate over $6 billion in sales volume annually. But when The Real Deal dug into that figure, we found it was heavily based on historical performance of those agents, in many cases from well before they joined Compass. The math becomes even more misleading when looking at a market like Los Angeles: Compass only launched there in November 2015, but counts its agents’ sales from May to November when reporting a tally of $1.06 billion for that market.

Compass also says it “recruited $80 million in annualized GCI [gross commission income] in the first two quarters of 2016,” an odd turn of phrase. That figure, however, appears to be all but meaningless when it comes to Compass’ own bottom line. The $80 million figure is the total commissions made by those new agents collectively during the past 12 months. Little to none of that amount has lined Compass’ own coffers.

Cash is king

It’s possible for startups to be profitable while also spending aggressively on growth. WeWork is one example, though it recently slashed its profit projections. Compass, though, is certainly spending more than it’s making.

“You can assume they’re burning through all that money,” said Zachary Aarons, a founder of real estate tech incubator MetaProp NYC. “Early investors want growth, and that torrid growth doesn’t come with profitability.”

There’s no doubt recruiting top talent from established firms and placing them in glitzy offices costs a lot. At 90 Fifth Avenue, for example, TRD estimates Compass’ annual rent at over $6.5 million, based on CompStak data that shows it’s paying somewhere between the high $70s and low $80s per foot for its nearly 90,000 square feet. In East Hampton, the firm is reportedly shelling out $300,000 a year in rent. And opening a typical brokerage office can cost a solid $100,000 — excluding rent and agents.

Many agents have been offered seven-figure signing bonuses or high splits, generous marketing budgets and other incentives, sources said. Most new agents get a 5 percent bump in their prior commission split for the first year. Some managers too, as TRD reported last year, have been offered salary hikes, signing and annual bonuses, and other perks.

“When they make an announcement that a new agent has joined, the conditioned response from the real estate community is, ‘I wonder how much they got paid?’” said Billy Jack Carter, an executive manager at Hilton & Hyland, a Los Angeles-based firm competing with Compass in markets such as Beverly Hills. “That approach doesn’t help them earn credibility. In fact, it works against them.”

Reffkin countered by saying recruitment is a more cost-effective way to grow than acquisition: Rather than buying smaller firms, which is a common way that brokerages expand, Compass opted to pick up just the top talent from firms both big and small, minus the fat. He claimed only 1 percent of top agent recruits were offered bonuses. A “very small minority” of new hires have been offered equity in the company, he said.

Compass’ New York and D.C. offices are both already profitable and all offices are designed to be financially self-sustaining within 18 months, Reffkin said. He claimed that if the company were to stop pushing for growth, every office would be profitable within the next six months, but declined to provide specific numbers.

“They keep having to go back to the well to raise more money because you can’t sustain a company when you’re having to pay recruitment fees as well as handing out aggressive splits, which in some cases, are as high as 100 percent,” said Jeff Hyland, a principal at Hilton & Hyland. “If we’re saying the average split is 80 percent, they have to be being paying 90 percent or more with perks for anyone that’s a top player. You can’t make money at that point.”

The Appraisal

Ever since Compass pivoted towards a traditional brokerage model in 2014, competitors have wondered: How can a company that looks and acts just like their own be so much more valuable? And how will its investors ever get their money back in such a low-margin business?

“It is commonly known within the industry that a fair valuation for a real estate brokerage firm locally and nationwide is five to seven times EBITDA,” said Town Residential founder Andrew Heiberger, who sold his previous firm Citi Habitats to a subsidiary of Realogy in 2004. “If a company earns $10 million per year, it should be worth $70 million or so.”

Compass justifies its far higher valuation by citing its software offerings, developed in-house by engineers with Google and Twitter pedigree. Those innovations, it says, are scalable.

“It’s something that can potentially power all real estate transactions across the country,” Compass co-founder Ori Allon told Fast Company last June.

The firm has apps that enable agents to promote open houses, schedule showings, provide real-time market intelligence to clients and create show sheets and pitch books, all with a few swipes. One of its newer tools lets agents instantly see a list of other agents (both within and outside Compass) who’ve recently done deals in a certain neighborhood or price range. And just this week, it launched a mobile app that gives real-time national data to potential buyers and renters.

These tools have attracted investors used to dealing with tech companies, including Joshua Kushner’s Thrive Capital, Founders Fund, .406 Ventures, Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff. And these investors, Reffkin claims, know that Compass is a long-term play.

Compass’ venture rounds (Credit: Crunchbase)

“Ori doesn’t need to make money again, I don’t need to make money again,” Reffkin said. His backers don’t expect to see returns anytime soon, he said. If they did want liquidity, Compass could always facilitate the sale of their stakes in the company on the secondary market, he added.

Reffkin said selling the company was off the table. While going public is “more likely than not, it’s not the goal.”

Several times during the interview, he compared Compass to Amazon, which didn’t bother with profitability in its early years and instead focused on developing its technology and attracting users. Amazon is now wildly profitable, worth nearly $300 billion and poised to cash in on its dominance in the U.S. e-commerce market. But Amazon has established a platform with more than 200 million users, making it very hard to compete with. Brokerage may not offer the same platform benefits.

The brokerage business

It’s important, then, to evaluate the startup as a brokerage. How does it stack up?

While Compass has been remarkably good at recruiting top talent — big-name hires in New York include Leonard Steinberg from Elliman and Kyle Blackmon from Brown Harris Stevens — sources said the company still lacks structure.

A TRD analysis of Compass’ New York listings volume last fall showed that Steinberg accounted for 51 percent of the firm’s total exclusives at the time. Competitors see that extreme dependence as a weakness.

“In New York City — where they have the most juice and the most agents — one agent has 50 percent of the listings,” said one brokerage head. “How is that representative of a model that’s fair to agents?”

There are other firms with this issue — Ryan Serhant had 57 percent of Nest Seekers International’s listings at the time of the analysis — and the fact that Steinberg has significant equity in Compass makes him less of a flight risk. But investors love scalable assets, and Steinberg isn’t scalable.

When it comes to new development, the golden goose of New York real estate, Compass has a mixed track record.

Thanks in part to its relationship with Aby Rosen’s RFR Holding, its landlord at 90 Fifth, Compass holds exclusives on $1.54 billion worth of new development inventory, according to a recent TRD analysis, including Rosen’s 100 East 53rd Street, which accounts for more than half that pipeline. But word on the street is that few units at the building are in contract — if any — and that the condos are overpriced for the current market.

Rosen declined to comment for this story.

Oddly, many of its investors haven’t thrown much business Compass’ way.

Miki Naftali, for example, was an early investor in Compass. But when choosing a broker for 275 West 10th Street and 221 West 77th Street, which together have a projected sellout of nearly $600 million, he went with Stribling & Associates. Kushner Companies’ Puck Penthouses were represented by Sotheby’s International Realty and now by Corcoran Group. Bill Rudin is also an investor, but Rudin Management’s flagship Greenwich Lane development, which has a projected sellout of $1.7 billion, is being handled by Corcoran Sunshine.

“The market is tougher now, too,” said an executive at one of the city’s largest residential firms. “There aren’t as many big deals. It’s easier for us to get exclusives than a new company. We always have a seat at the table.”

There’s also been lots of churn in Compass’ new development division: Roy Kim, former head of new development; LaVon Napoli, former director of new development marketing; Ben Fortuno, manager of design; and former analyst Josef Goodman are out.

Louise Sunshine, who came on board in January to advise Compass on expanding its new development division, left the firm in less than six months.

“My business practices and those of Compass were not aligned,” she told TRD at the time. “Compass, they have their own way.”

On Monday, Compass announced its new development division was going national, to be led by Hana Cha and Morgan Ball, two former new development executives at the Agency. But so far, its forays outside of New York have met with mixed results.

In the Hamptons, for example, one of its agents, Ed Petrie, brokered a record $110 million sale. But it has also been dealing with two lawsuits: one brought by Brown Harris Stevens alleging unfair competition, and another by Saunders & Associates alleging that one of its former agents stole listings and gave them to Compass.

Meanwhile, Compass is yet to launch in cities like Chicago, Houston and San Francisco, which it had identified as target markets as far back as 2014.

Reffkin said based on agent demand, Compass re-prioritized which regions to tap next. So instead of launching in cities like Chicago, new priorities are California markets such as San Francisco, Santa Barbara, Montecito, Pasadena and Brentwood, as well as Cambridge, Mass.

He acknowledged secondary-home cities such have been tough to crack. “Miami’s been a difficult market because there’s been a slowdown,” he said.

Former Compass employees echoed Sunshine’s sentiment, saying the startup’s principals have very different priorities than typical brokerage chiefs.

“They’re approaching the business from a very ‘investment banker, management consultant’ mindset,” said one. “People who work at Bain, McKinsey, Boston Consulting or PwC really have a leg up there. That’s more important [for them] than experience in the real estate business.”

Correction: In an earlier version of this story, TRD incorrectly characterized Compass’ claim that it had acquired $80M in GCI. The $80 million figure represents the total commissions made by those new agents collectively during the past 12 months.