Home prices in China are “high and hard to accept,” said 53.7 percent of the respondents in a survey by the People’s Bank of China, published in the People’s Daily, the official paper of the Communist Party. Only 42.9 percent found them “acceptable.” And only 23.1 percent predicted that they would rise next quarter, while 11.9 percent expected them to fall. But that isn’t stopping people from wanting to participate in this frenzy.

“Nevertheless, the ratio of residents who were prepared to buy a house within the next three months increased 1.3 percent from the third quarter to reach 16.3 percent,” according to the People’s Daily.

That’s a lot of people “prepared to buy a house,” even with prices “high and hard to accept.”

There are several remarkable things in this survey: the worried tone in terms of the soaring prices, the increased desire to buy because, or despite, of the soaring prices, and the fact that this survey came via the official party organ from the PBOC which has been publicly fretting about the housing bubble, the debt bubble that comes along with it, and what it might do when it deflates.

And what a bubble it is!

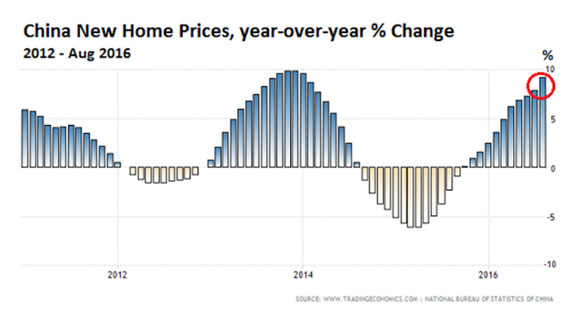

The average new home price in 70 Chinese cities soared 9.2 percent in August year-over-year, after having jumped 7.9percent in July, the eleventh month in a row of year-over-year gains, according to the China Housing Index, reported by the National Bureau of Statistics. In Tier 1 cities, prices skyrocketed: in Beijing, by 23.5 percent and in Shanghai by 31.2 percent!

Prices increased in 64 of the 70 cities, up from 51 in July. They fell in only four cities and remained flat in two. This chart bytradingeconomics.com shows the year-over-year percentage change in new home prices, the boom and bust cycles, and the stage of the boom where prices are at the moment:

Housing construction is critical to the Chinese economy. When construction suddenly slows down, as it does when the housing bubble deflates, it has deep and broad effects. And this phenomenal home price bubble and the construction bubble that comes with it are funded by ballooning debt: outstanding bank loans to households, mostly mortgages, surged 21 percent in August year-over-year, according to Bloomberg’s math.

“The more immediate risk of a sudden and steep downturn in the economy comes from the threatened bursting of the property market bubble,” Pauline Loong, managing director at research firm Asia-analytica in Hong Kong, wrote in a report, cited by Bloomberg. “The real question for investors is when and what will pop the bubble?”

The central bank has been out there, trying to gently deflate the Chinese property price bubble before it pops violently. Ma Jun, chief economist of the PBOC’s research bureau, warned in an interview September 11 interview:

“Measures should be taken to put a brake on the excessive bubble expansion in the property sector, and we should curb excessive financing into the real estate sector.”

According to a note today by JPMorgan Chase analysts led by Zhu Haibin, paraphrased by Bloomberg: “One difficulty in reining in the home-buying frenzy is the larger leverage residents used through commercial banks with a growing appetite on mortgage loans.”

Other measures of credit soared too in August. Aggregate financing, the broadest measure of lending, hit 1.47 trillion yuan ($220 billion), far exceeding expectations. The voices of concern, according to Bloomberg, are accumulating:

“Monetary policy is obviously loose and liquidity is ample,” said Zhao Yang, chief China economist at Nomura Holdings Inc. in Hong Kong. “The loans almost all went to the property market due to surging prices in big cities.”

“Monetary policy is pushing on a string and we are reliant on state lending, spending for recovery,” said Michael Every, head of financial markets research at Rabobank in Hong Kong. “But that can’t last forever. It’s a clear sign that there is a liquidity trap.”

Regional and local governments have also been trying ineffectually to tamp down on the frenzy before it blows up wildly. Shanghai and Shenzhen imposed some home-buying limits in March. Other governments followed, according to Bloomberg:

Hangzhou, Zhejiang’s provincial capital, on Sunday halted home sales to some non-local residents, adding to similar bars introduced last month in nearby Suzhou and the southern port city Xiamen. More second-tier hubs, including Jiangsu’s provincial capital Nanjing and Hubei’s Wuhan increased down-payment requirements in bid to dent demand from speculators.

More governments are expected to announce curbs on home buying. But these measures are unlikely to work very well unless the central government and the PBOC tighten credit and mop up some liquidity. But that’s exactly what could bring this whole construct crashing down. So for now, the PBOC might instead refrain from loosening its monetary policy further and attempt to jawbone down home prices and mortgage lending, or at least keep them from inflating further, via interviews and surveys. This is tricky business in an economy that runs on monetary fumes.

House price declines have caused uproars in China, which is exactly what authorities fear more than anything. But they also fear bubbles, having seen how they implode – and cause uproars.