A lot of the same cranes that dotted the skyline last year will keep swinging away in 2017. But when they do come down, there are certain to be fewer going up in Their Place.

That’s because both approved residential construction permits and new permit applications fell significantly in 2016, according to The Real Deal‘s analysis of data from the city’s Department of Buildings.

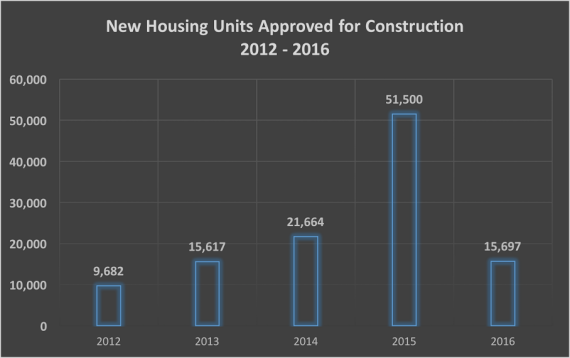

There were approximately 15,697 new units of housing across the city approved to begin construction last year, a 70 percent plunge from 2015’s frenetic, 51,500-unit spree.

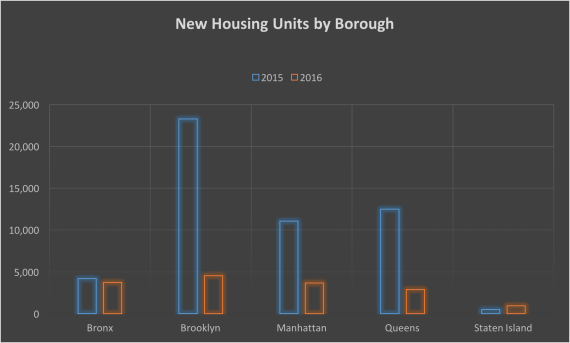

Permits dropped year-over-year in every borough except for Staten Island, where the number of approved units rose from 476 to 920, according to the data.

The largest drop was felt in Brooklyn. In 2015, developers put stakes in the ground to build 23,393 new housing units in Kings County. But in 2016, the borough unit count was down to a paltry 4,535.

Despite the huge downward shift in unit count, the number of approved residential projects only fell 16 percent from 1,882 projects to 1,577 projects. Essentially, developers in 2016 moved forward with more modestly-sized plans on new construction residential projects. For projects of at least 10 units, the average unit count was 84 apartments in 2016 versus 63 in 2015.

Source: TRD analysis of initial new building permits issued by the DOB. Excludes known hotel projects.

While it’s not entirely clear why permits declined so markedly last year, a fracas around tax incentives for builders is likely the biggest factor.

The bulk of the units approved in 2015 came during two rushes to beat expiring 421a tax exemptions for residential construction (in June and December of 2015, respectively). Those permit runs cleared out a lot of the pipeline that under normal circumstances— when developers are not under as much pressure to expedite plans—might not have been approved until 2016, juicing the totals of the previous year.

“When everyone wanted to get the permits under 421a you saw a big rush,” said Carlo Scissura, the new president of the New York Building Congress construction trade group. “So I’m not sure the fact that the numbers went down so much is really that much of a thing.”

“A lot went under construction in Brooklyn fast,” Scissura added, “and you’re seeing less of that now, but that doesn’t mean that the economy is bad in Brooklyn, it just means the big projects have already gone in.”

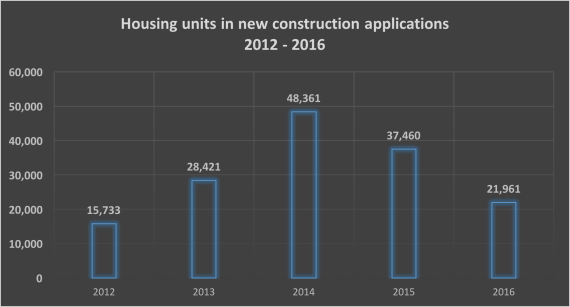

Even so, the number of new applications submitted has also fallen over the last couple of years, indicating more recent softening in development plans. Last year saw about 22,000 units included in brand new building applications, down around 41 percent from 2015 and 55 percent from 2014.

When issued permits broke records in 2015, then-head of the Building Congress Richard Anderson told the Wall Street Journal that “we are heading into the stratosphere.” While the permit figures have since come down markedly, the city could be in for another spike if 421a is renewed. The legislative session kicked off just last week, and the two major stakeholders — developers and union labor — have already struck an accord on wage provisions, the biggest hurdle since the abatement expired.