Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s proposed replacement to 421a could cost the city $8.4 billion in property tax revenue over the next 10 years, according to a new report that perhaps further fuels the sniping between Albany and City Hall over the lapsed abatement.

The Independent Budget Office released a two-page report late Monday that estimates the governor’s proposal to revive 421a — called Affordable New York — will cost $2.3 billion more than the plan Mayor Bill de Blasio floated in 2015. The report also estimates that the governor’s program will cost the city $1.2 billion more than the legislation that was enacted in June 2015, an average of $120 million more per year and $1,440 more per apartment each year.

The short report is based on data provided by the Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) and the mayor’s office, though it doesn’t break down how these numbers were arrived at. In January, HPD told Politico that the governor’s plan would cost $82 million more per year than the one the mayor proposed.

“There are clearly significant additional costs associated with the newly proposed 421a law,” Melissa Grace, a spokesperson for the mayor, said in an email. “Making sure we secure an appropriate degree of value for taxpayers is our obligation.”

A spokesperson for Cuomo’s office would only reiterate a statement put out earlier this year, saying “any expenses in exchange for making sure that all New Yorkers have a safe and decent place to call home are minimal, 26 years out, and worth it.”

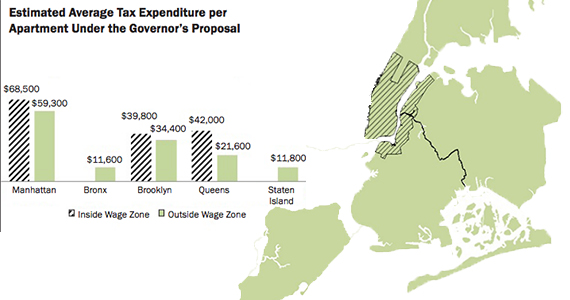

Estimated average tax expenditures per apartment (credit: IBO, edited for space)

Cuomo introduced Affordable New York in January, and since then, the governor and mayor’s administrations have taken turns swinging at each other. Just days after the program was announced, de Blasio voiced concern about unforeseen costs to the city and that more condominium projects might find their way into the legislation. Last month, the state’s outgoing housing commissioner Jamie Rubin blamed de Blasio for the program’s extra costs. He said the mayor’s proposal for the abatement served as the foundation for the June 2015 legislation, and was “much more expensive,” but will also create “much more affordable housing.” He said the only difference with the governor’s Affordable New York program was the “change that was necessary to restart the program.”

But the IBO report points to just those changes as largely the cause for the extra costs. The changes include construction wage requirements for projects south of 96th Street in Manhattan and along the waterfronts in Brooklyn and Queens. These projects, as well as certain large developments that opt to pay the wages, are eligible for an extended 35-year abatement. The report projects that the city will pay $68,500 per apartment in Manhattan’s wage zone, compared with $59,300 outside it. In Queens, the city would pay $42,000 per apartment in the wage zone compared to $21,600. In Brooklyn, the city would pay $39,800 to compared to $34,400.

Still, the IBO report doesn’t account for the argument put forward by many of New York City’s leading developers: That without the tax abatement, rental development just isn’t feasible. The report seems to assume that the revenue-producing projects would be created with or without a 421a program in place.

Geoffrey Propheter, a property tax analyst for the IBO who prepared the report, acknowledged that while the lost tax revenue could be an overestimation, it’s likely a small one. He said the projects that “live or die by 421a” — those in lower-income areas — tend to expend less property taxes anyway. So, even if those properties weren’t included in the report, the numbers would likely be roughly the same.

“It’s kind of like throwing a lawn chair off of the Titanic,” he said.