In March, Airbnb raised $1 billion from investors in a funding round that valued the short-term rental company at $31 billion. It’d be easy to treat that huge sum as another case of Silicon Valley’s swashbuckling venture investment culture, except a big chunk of the money didn’t actually come from there. It came from China.

The sovereign wealth fund China Investment Corporation chipped in $100 million, regulatory filings show. And Airbnb was just one of several real estate-related tech startups that looked across the Pacific for funds. Last year, WeWork landed a staggering $690 million from Chinese investment firms Hony Capital, Legend Holdings and Shanghai Jin Jiang International Hotels, valuing the co-working company at $16.9 billion. Real estate tech startups like LendingHome, Fundrise, Cadre, RealtyShares and Roofstock also raised money from Chinese firms.

The emergence of Chinese venture capitalists isn’t just shifting the balance of power in investment circles. It could also be a game changer for startups looking to expand globally.

“It’s sort of the holy grail for startups that have some sort of appetite to enter the Chinese market,” said Nav Athwal, founder of real estate crowdfunding company RealtyShares. The goal is to tap into a country where “there’s billions of potential users of technology applications and the number is only growing.”

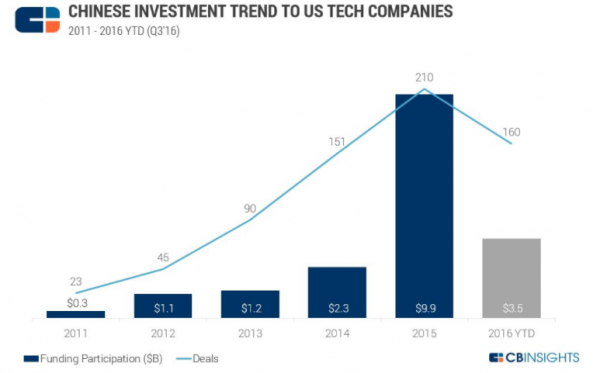

Between 2011 and 2015, annual Chinese investment in U.S. technology companies rose from $300 million to $9.9 billion, according to research firm CB Insights, before falling in 2016 amid a general slowdown in venture investment. The data doesn’t break down how much money went into real estate technology, but sources said it holds a special appeal to Chinese investors.

“They feel like they know it,” said Veronica Wu, managing partner of Hone Capital (not to be confused with Hony Capital), the U.S. arm of the $10-billion Chinese private equity firm CSC Group. “If you talk to people in China, 90 percent made their money in real estate.”

Many Chinese have a well-chronicled affinity towards investing in real estate, and property played a big role in China’s growing wealth over the past two decades. This helps explain why Chinese firms have been such active investors in U.S. real estate in recent years (see chart), and it can also explain their newfound enthusiasm for property tech companies.

Hone is backing the real estate investment platforms Roofstock, RealtyShares and Clara Lending, the Airbnb competitor Overnight and the drone-based property inspection service BetterView, among others, making it one of the most active Chinese investors in the space. The social media company Renren invested in mortgage platform LendingHome and crowdfunding company Fundrise, among others. Alibaba founder Jack Ma is an investor in Cadre, the Jared Kushner-backed real estate investment startup.

Wu, who previously headed up Tesla Motors’ Chinese operations and launched Apple’s enterprise business in China, joined CSC in April 2015 to oversee its expansion into the U.S. The company opened a small Palo Alto office, and said it has invested close to $40 million in early-stage startups (Wu reckons around 10 percent of that went to real estate tech firms) and another $100 million-plus in later-stage companies.

It hasn’t been easy. Having a parent company overseas means Hone (formerly known as CSC Venture Capital) can’t always move as quickly as its U.S. competitors. And making firm commitments can be tricky in the face of Chinese financial regulations.

“If you’re committed to a deal and all of a sudden you can’t get the money out (of China) you instantly lose credibility,” Wu said. “I always over-communicate (with the CSC headquarters) to make sure the money is going to come out. It’s definitely a much longer process and you definitely need to plan much longer term.”

The fact that Chinese firms are relatively new to the U.S. market is another challenge. Many startups dream of convincing Silicon Valley luminaries such as Sequoia Capital or Andreessen Horowitz to lead an early round and thus instantly gain status. Foreign firms that have yet to build a reputation struggle to compete.

“Our biggest disadvantage is that nobody knows you,” Wu said. “It’s a constant Catch-22.”

But if Chinese firms are on the back foot in early funding rounds, they become more competitive as startups grow and start eyeing Chinese customers. Athwal, who raised money from CSC for RealtyShares’ Series B round, said the company wants to open its investment platform to the Chinese market and has held talks with potential investors.

“Eventually every company wants to enter the Chinese market because it’s one of the largest markets out there, and obviously it’s very hard to enter that market without some local presence,” he said. “As we raise future rounds, we’re definitely going to look to China for a lead position or participating position.”

Matt Humphrey, co-founder of LendingHome, first met Renren’s executives in late 2014. Like Athwal and Wu, they were connected through a U.S. venture investor. In April 2015, Renren led LendingHome’s $70 million Series C round.

Humphrey said having Renren as a backer made it easier to win over Chinese customers for its platform, which sells U.S. mortgages and mortgage bonds. It “helps give a significant level of comfort for investors over there,” he said.

It’s probably no coincidence that WeWork and Airbnb both landed big investments from China as they were preparing to expand there. WeWork opened its first Shanghai location in July, four months after raising $430 million from Beijing-based Hony Capital and Legend Holdings. “We’re grateful to Hony Capital, our partners in the region, for helping us realise our vision for WeWork in China,” the company’s CEO Adam Neumann said in a statement announcing the new space. And two weeks after Sky first reported CIC’s $100 million investment in Airbnb, the company announced it would adopt the name “Aibiying” (爱彼迎) to appeal to local customers, double its investment and triple its staff count in China.

U.S. tech startups may be more keen than ever on Chinese capital, but regulators are raising the hurdles. At the end of 2016, Beijing issued a series of capital controls designed to promote investment at home and stabilize the country’s foreign-exchange reserves. The move hit New York’s real estate market hard, and is also hurting startups. No one knows when the controls will be lifted, and Humphrey said they “have made it a good deal more difficult for folks to get capital out.” If they remain in place indefinitely, they may well put an end to the Chinese VC rush.