The Bronx has become a destination for investors seeking high returns – not only in new development, which is, by any measure booming, but also in the borough’s existing apartment building stock.

Take Prana Investment’s purchase of 65 East 175th Street. In 2014, the San Francisco-based firm paid $4.5 million for the five-story building in the Mount Hope neighborhood and sold it less than two years later for $7.3 million, a 32 percent annual return on the sale price.

Prana’s sale was part of a larger trend. From 2010 to 2016, city property records show that investors spent $9.2 billion snatching up Bronx apartment buildings. Deal flow has continued into this year with major purchases such as MDG Design + Construction’s $78 million deal for over 500 units in the Melrose neighborhood.

But even though some sellers have made a killing on their properties, the buildings aren’t generating nearly enough income to keep pace with the sales prices, according to an analysis conducted by The Real Deal.

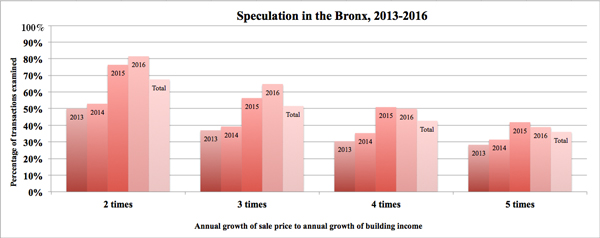

In over half of apartment building transactions between 2009 and 2016, market prices grew at least three times faster than building net income – a disconnect pointing to investor speculation that the fundamental value of buildings will catch up to their sticker price as rent rolls in the borough increase. The assumption, though, may not pan out, and depending on the terms of investors’ debt, overpriced acquisitions may put investors in a difficult position.

Our analysis considered transactions speculative if prices grew at least three times faster than building income, which has happened more and more in recent years. In 2013, roughly 37 percent of transactions identified by TRD experienced a pricing increase at least three times as fast as growth in net building income. The number rose to 39 percent in 2014 and jumped to 56 percent in 2015. In 2016, the figure reached 65 percent of transactions identified, according to TRD‘s analysis.

In 43 percent of transactions, growth in sale pricing grew four times faster than growth in building income during that eight-year stretch, indicating highly speculative deals. The data reveal a clear disconnect between how investors value Bronx apartment buildings and the income the buildings yield.

Joe Pistilli of Pistilli Realty Group — which purchased the property at 65 East 175th along with three other buildings from Prana in separate transactions — said the buildings were turning a profit.

“The market is demanding what people are willing to pay for the properties,” he said.

To determine how many of these Bronx investments are speculative, TRD examined property tax and sale records of elevator and walk-up apartment buildings that were sold and resold between 2009 and 2016. The search identified 225 transactions in that period where the data allowed us to compare the sales. Each set of transactions included at least one purchase price over $1 million and at least a year between sale dates.

The analysis used the two sale prices to gauge investor pricing in the borough and to determine a property’s annual rate of return. We then examined the annual growth of the building’s net operating income (NOI), which measures the difference between a building’s expenses and its revenues and is based on numbers landlords self-report to the Department of Finance. (In some cases, buildings were sold in groups of two or more, and the figures were adjusted accordingly.)

Since the most recent NOI data available reflects income from 2015, TRD estimated 2016 net income by assuming that a building’s NOI grew at a constant rate since 2011. Analyses excluding 2016 sales revealed similar overall findings.

The data points are not perfect, as income is measured on an annual basis while sales take place throughout the year. But they do offer a deeper picture of the Bronx investment scene.

“The pricing today is very high as opposed to even five years ago,” said one investor whose firm has been active in the borough. The investor, who requested anonymity, said that the “extraordinarily hot” market might stem from the borough’s relative cheap property costs compared to other areas in the city, a sentiment shared by some brokers and investors.

In 2016, walk-up apartment buildings in the Bronx averaged $167 a square foot and elevator apartments averaged $190, Cushman & Wakefield data show. That’s compared to $1,063 per square foot for Manhattan walk-ups and $955 per square foot for elevator apartment buildings. (Northern Manhattan averaged $393 and $361 a square foot for walk-ups and elevator apartments, respectively.)

Investors can also potentially get more for their money by buying buildings in the Bronx. According to data provided by Cushman, average capitalization rates, the ratio of building income to its market value, rested at 5.01 percent and 5.77 percent, respectively, for Bronx elevator and walk-up apartments in 2016. Cap rates for Manhattan elevator and walk-up apartments averaged 3.3 percent and 3.71 percent, respectively, with slightly higher average rates of 3.78 and 4.07 in northern Manhattan.

“People are still very bullish on the Bronx,” said Aaron Jungreis, co-founder of Rosewood Realty Group. “I just see people pumping more into the neighborhoods.”

Seth Pinsky, an executive vice president at RXR Realty, said “there’s every reason to believe the rebirth of the Bronx is real and sustainable,” noting that RXR has been keeping the borough on its radar but has yet to invest.

“The question is as always: How fast it will happen and how far it can go,” he added.

$200K a door?

Jonathan Miller, CEO of appraisal firm Miller Samuel, sees rising prices in the Bronx as being part of a larger trend. “There’s a flood of capital worldwide seeking a home,” he said. “Sometimes the financials don’t always make sense.”

The rise in speculative investments dovetails with increased interest in the borough. Dollar volume of multifamily apartment building sales over $1 million have more than doubled between 2010 and 2016, peaking at $1.8 billion in 2014, according to TRD’s analysis. And the annual number of sales has increased by over 50 percent between the two years.

“In the past few years we’ve seen more demand for pretty much every property type,” said David Simone, a Bronx-focused broker at Cushman. “There seems to be strong appetite for Bronx apartment buildings.”

As demand has increased, so too have prices. “The normal asking price now seems to be $200,000 a unit on up,” said Jim Buckley, director of the Bronx-based University Neighborhood Housing Program (UNHP), which has been looking at speculative buying in the Bronx for over a decade.

Data compiled by UNHP shows that average per-unit sale prices have fallen short of this mark, but the increase between 2011 and 2015 is clear. The sale price per unit in multifamily apartment buildings has roughly doubled in this time, closing at nearly $150,000 per unit by the second half of 2015.

“I think the prices are much too high,” said Steve Finkelstein, whose firm, Finkelstein Timberger East Real Estate, invested roughly $180 million in Bronx apartment buildings from 2009 through 2014.

“There are people out there still buying,” he said. “I don’t agree with their valuation, so I’m kind of out of the market right now.”

Pistilli, speaking about the company’s Building On 175th Street, said the economics “aren’t all based on the net income.

Joseph Pistilli (credit: “BuildingNY” via YouTube)

“There are many different conditions,” he added, saying that long-term holders rely on strong appreciation values.

Other investors remain optimistic, too, especially about buildings in the Kingsbridge, Mount Hope, University Heights, and Melrose neighborhoods. In fact, four of the borough’s 25 ZIP codes account for nearly half of speculative sales identified between 2010 and 2016.

Prana’s Investment On 175th Street falls in one of these areas in the West Bronx, and its 32 percent return on the building’s sale price is over three times higher than the building’s growth in income during that same time, according to DOF data. The company declined to comment for this story.

Some lenders aren’t thrown off by the price growth in the borough. George Klett, head of commercial real estate lending at Signature Bank, expressed optimism in the growth of Bronx investments. But, he noted, buyers have had to put more skin in the game to keep up with the borough’s pricing, “because we wouldn’t give them the money they were looking for.”

Another lender said investors were often ponying up between 30 and 40 percent of equity for acquisitions.

Fears of Displacement

Buying on the expectation that building values will appreciate is not abnormal – the process can lead to increased development, like the revitalization of the old post office building at 58 Grand Concouse – and bubbles can mature as fundamentals catch up to market pricing.

But some community groups are concerned for how this speculative buying will impact tenants in a borough where a majority of apartments are rent-stabilized and incomes rest at citywide lows. The fear is that all the activity could displace the area’s residents and landlords might resort to predatory behavior in order to boost returns.

The average speculative transaction between 2010 and 2016 comprised buildings where 83 percent of residential apartments are now rent-stabilized, according to June 2016 property filings. Rent-stabilization laws limit the amount landlords can charge tenants, and in the last two years the mayor-appointed board tasked with setting annually allowed increases opted to freeze rents for stabilized tenants signing one-year leases — although a preliminary vote last month suggests increase are coming this year.

Clockwise from left: maps of zip codes 10453, 10457,

10468 and 10458 (Credit: Google Maps, Click to enlarge)

Landlords can also raise rents after making improvements to the apartment or building – or after a tenant moves out. Some community groups argue these exceptions provide an incentive for landlords to push tenants out to increase rents.

Sheila Garcia, deputy director of Bronx-based tenant organizer Community Action for Safe Apartments (CASA), said she has seen cases of landlords trying to “intimidate people in order to displace them.”

Community groups like CASA refer to speculative purchases and subsequent tenant removal techniques as “predatory equity.”

Last June, Bronx city Councilmember Ritchie Torres introduced a bill that would create a watch list for so-called predatory equity landlords, partially defining the practice as taking on more debt than the building’s income can initially support.

Ritchie Torres (Credit: Getty Images)

“We’re seeing landlords still try to go to extremes to be able to push the limits of the law and illegally harass tenants out of their apartments as well,” said Alejandra Nasser of Stabilizing NYC, a coalition of tenants’ rights groups. Speaking at a public meeting last month in front of the Rent Guidelines Board, Nasser said that the coalition has worked in what she defined as “predatory equity buildings” throughout the city.

Predatory or not, investors continue to speculate on the Bronx, and judging by the trades in the first quarter, are likely to keep upping their bets. But to what end?

“Everybody’s looking for the next Williamsburg or Bushwick,” said David Schwartz, a principal at Slate Property Group, which said it intends to steer clear of the Bronx for now. Williamsburg saw sales prices double from the second quarter of 2008 to the second quarter of 2016, from $668,956 to $1.3 million, according to Miller Samuel data. In that same period, average monthly rents in Bushwick jumped 70.6 percent, to $2,643.

Investors may be hoping that Bronx neighborhoods follow a similar trajectory and push property values skyward.

“I don’t know if that’s the right assumption,” Schwartz said.

Yoryi DeLaRosa contributed research.