When Barry Sternlicht talks, the real estate industry listens. Earlier this month, the Starwood Capital chief used his pulpit to address a subject New York players often like to downplay: the city’s increasing dependency on foreign capital even as geopolitics is being upended.

“If you are having a fight with our administration, you are just not going to invest here,” Sternlicht said. “They are very quick to shut down the capital flows… It has to do with politics.” Sternlicht was talking about Qatar, whose government has been at odds with the Trump administration for months. But he could have easily been referring to China, or the European Union.

The rise of foreign investment in Manhattan over the past few years has been a boon to the real estate industry. But as 2017 passes the mid-year mark, the trend’s flipside is increasingly becoming apparent.

Back in November, Chinese capital was still king here, paying top dollar for the glitziest assets and telegraphing much more to come. Then Beijing took action, and things changed rapidly. The Chinese government began enacting a series of controls designed to curb capital outflows, particularly bets on what it deems risky investments. When The Real Deal took an in-depth look at the issue in May, brokers channeled their supernatural optimism and said they don’t see it having a big impact on New York. It’s getting harder to defend that stance now.

This month, Morgan Stanley reported that Chinese overseas real estate investment could fall by 84 percent this year. And Chinese regulators formalized capital controls, vowing to no longer tolerate “irrational” investment overseas, particularly in real estate.

The head of real estate at Anbang Insurance Group, owner of the Waldorf Astoria and Essex House hotels, left the firm, two months after his boss, Anbang’s chairman Wu Xiaohui, was suspended.

And Dalian Wanda scrapped plans to pay over $600 million for a site in London amid increasing scrutiny from the Chinese government. The company is also combating rumors about the detainment of its chairman, Wang Jianlin.

And it’s not just the Chinese. Take Korean investors, who bought the New York Palace Hotel, a fat stake in SL Green Realty’s One Vanderbilt and have become increasingly important players in the debt space. They could become an endangered species if the standoff over North Korea’s nuclear weapons program spirals into a regional crisis or even a war. And then there’s Qatar, whose sovereign wealth fund and royals invested in Brookfield’s Manhattan West, Empire State Realty Trust, Harry Macklowe’s One Wall Street and Michael Stern and Kevin Maloney’s 111 West 57th Street.

The problem is that several big overseas investors retreating from New York would no longer just be a hiccup — it could shake the market to the core.

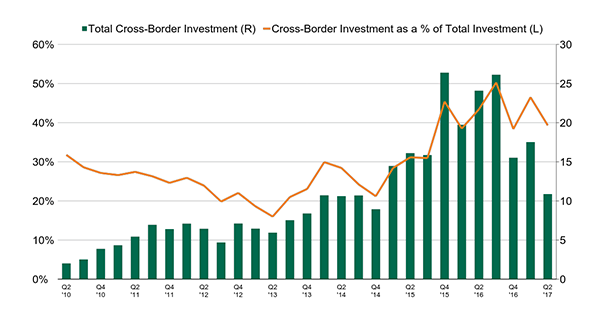

The chart below, shared by CBRE, shows the rise of foreign investment in the city. Between 2010 and 2015, the share of investment coming from overseas was rarely ever above 30 percent and even dipped below 20 percent in 2013. But since mid-2015, it has averaged more than 40 percent, hitting a high of 50 percent last year.

Credit: CBRE

Much of that money comes from regions such as Canada and Europe, which are generally thought of as more consistent and measured capital sources. But even here, macroeconomic shifts could disrupt things. “Into late 2016, the cost to hedge the US/Euro exchange rate was growing. Conservatively leveraged German investors pulled back on their investment activity by 17% in 2016 versus 2015 as a result,” Real Capital Analytics’ Jim Costello wrote in a report earlier this year.

All that money’s impact may be even greater than these numbers suggest, because foreign buyers often bid top dollar for trophy assets, setting new benchmarks for pricing.

“All the markets price off the top bid and the top bid has been an Asian bid, whether it was the sale of the Waldorf or the bailouts of a Strategic Hotel deal,” Sternlicht said. “Everybody thinks they are rich when the guy pays the 2 percent cap for an asset, or a 1 percent cap. If there are six bids at $1 billion and one guy is at $1.5 billion, I would ask you to tell me where the loan-to-value is of the loan, right?”

It may not be a coincidence that the spread between the average cap rate of prime Manhattan properties and the 10-year Treasury yield (an imperfect but useful indicator of how overpriced a market is) is far lower now than it was in 2012 or 2013 (see chart, courtesy of RCA).

Credit: Real Capital Analytics

“I don’t think you can ignore what’s going on globally,” said Savills Studley’s Heidi Learner. “It’s not just true for commercial real estate.”

Kushner Companies learned this lesson the hard way. Shortly after the election, the firm’s executives reportedly toasted with Anbang’s Wu on a deal to fund 666 Fifth Avenue’s conversion into a new luxury condo and retail tower. But the deal fell apart this spring, and Kushner, which will see its interest payments on the building spike in a few months, has yet to announce a replacement.

The point is not so much that Chinese, Japanese and Korean investors will necessarily retreat from New York. It’s that they could, that the likelihood has probably increased slightly since November (although it’s still very unlikely) and that the impact would be immense.