TRD Special Report: In late July, around the time the FBI raided his Virginia home, former Trump campaign chair Paul Manafort was out making real estate deals.

Manafort, who spent decades as a Washington power broker for oligarchs and dictators, was attending a meeting at the New York office of architecture firm Perkins Eastman. The group, which included representatives from engineering firm Langan, sipped Trump-branded water and perused printed materials.

There with Manafort was his client Yan Jiehe, the billionaire who heads Pacific Construction Group, China’s largest privately owned builder. Manafort had been working with Jiehe since at least the spring, advising the company on global infrastructure contracts. According to Brad Zackson, Manafort’s real estate fixer and the man who brought all the parties together for the July meeting, Manafort was helping Pacific identify U.S. construction firms that were ripe for acquisition.

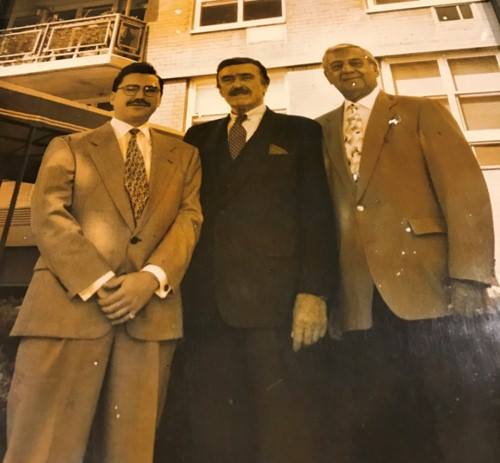

At a separate meeting, Manafort and Jiehe posed for a photograph with principals of one of these potential targets, Munilla Construction Management, a Miami-based firm that has a Pentagon contract to develop a school for the U.S. Navy at Guantanamo Bay in Cuba. Zackson posted that photograph on his website.

At center, from left to right: Paul Manafort, Yan Jiehe, Brad Perkins and Brad Zackson

Manafort is one of the most scrutinized men in the country and a central character in Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into the Trump campaign’s ties to Russia. But despite the spotlight, he appears to be trying to put together major real estate deals with a motley crew from across the globe. (A potential deal between a foreign firm and a U.S. firm doing sensitive government work, such as Pacific acquiring Munilla, could attract the attention of the Treasury Department.)

A common denominator in those deals, both past and present, is Zackson, a veteran New York real estate operative who is far from a household name in the industry but has long aspired to be one.

“All I’m gonna say, you’ll see shortly, is it’s all lies,” Zackson told The Real Deal about the heat on Manafort and the media coverage he’s received. “Complete lies. I’m surprised at some of the people that are writing them.” Manafort did not respond to several requests for comment.

In 2008, Manafort and Zackson made an unsuccessful run at the Drake Hotel site (now home to 432 Park Avenue), backed by equity investments from a Russian metals billionaire and a Ukranian natural gas mogul who are both now suspected of criminal activity. That deal triggered a federal investigation now being run by Mueller.

In the decade since the Drake plan fizzled, Zackson, a convicted felon who became a protégé of Donald Trump’s father, Fred Trump, has tried to position himself as a master developer whose best projects are yet to come. Among these, he said, is a plan to build an apartment complex in Queens’ Willets Point neighborhood that would dwarf Stuyvesant Town and a run at the Roosevelt Hotel in Midtown.

Much like Manafort, Zackson’s real estate career is dotted with controversy. Deals tend to include a revolving cast of foreign tycoons, assorted cronies and, in at least one instance, Trump himself. In comparison with the likes of Bayrock Group principals Felix Sater and Tevfik Arif, Zackson is a lesser-known character from Trump’s old stomping grounds of high-stakes property deal-making. But understanding him is key to understanding the bare-knuckled, truth-optional world Trump inhabited and continues to reflect in his approach to the presidency.

“On the surface when he speaks to you, it seems like a great story,” Kevin Maloney, founder of Property Markets Group, said of Zackson, whom he’s battling in court. ”When you dig down, it’s not true — or it’s only 10 percent true. That’s the truth of it. There’s nothing beyond his stories, and when he gets to the end of the story, he will inevitably ask you for money.”

Get me Brad Zackson!

Now 57, Zackson is a stocky man who dresses like he wants to be taken seriously: pinstriped suits, waistcoats, a pair of glasses perched on his forehead and another pair dangling around his neck. His website is filled with photos of him posing with world leaders such as Bill Clinton and Fidel Castro, as well as New York politicians such as Andrew Cuomo and Rudy Giuliani. On his site he touts projects that never panned out, such as the Drake and Biscayne Shores in Miami Beach, as “predevelopment” achievements.

It’s a portrait of a well-connected macher that Zackson has put a lot of effort into cultivating. And with good reason.

In 1981, he was arrested on charges of criminal possession of a weapon and attempted murder in the second degree. Court documents show that Zackson, his brother Stephen and a third associate, Rory Schonhaut, allegedly attempted to shoot a club bouncer, Ronald O’Hare. Zackson dodged the attempted murder charge by taking a plea deal that saw him serve almost five years in prison, records show.

“The bouncer beat up this guy Rory and Rory came back and shot at the club’s door,” Zackson said. “It was just a bunch of kids fighting and I got accused of it also. We were just crazy kids from Queens. It was a terrible thing but it was 30 years ago.”

After his stint in prison, Zackson became a rental broker and quickly gained a reputation as a hustler who could get deals done. According to a 1995 Crain’s report, a limousine arrived one day at Zackson’s Jamaica Estates office. He had been summoned by Fred Trump, who owned many of the buildings Zackson was working in and wanted to meet the young man who was renting them out at a furious pace.

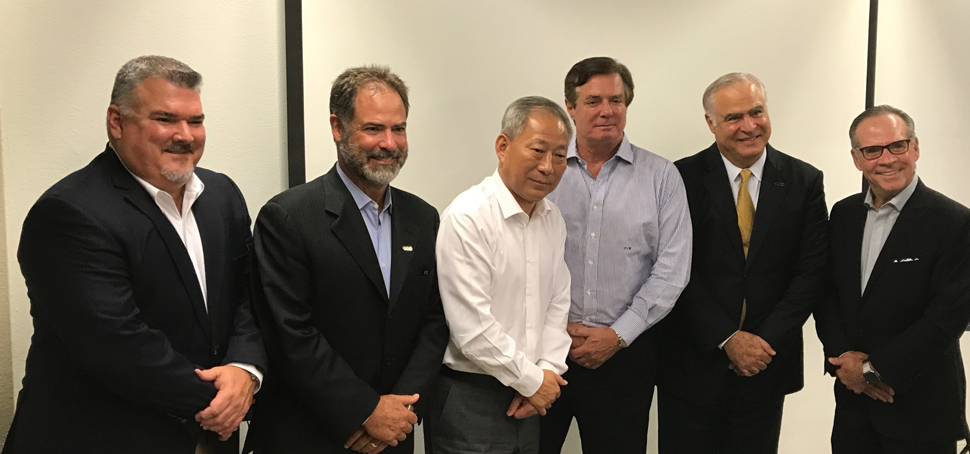

Zackson, who in those days sported a mustache similar to Fred’s, kept vacancies so low in the Trump Organization’s outer-borough portfolio that Fred put him in charge of all the company’s Queens buildings. Later, Zackson left the firm and focused his energy on his own brokerage and investment firm, Dynamic Group, after Fred, in his words, “aged out.”

From left to right: Brad Zackson, Fred Trump and Irving Eskenazi (Credit: Dynamic Worldwide Group)

He shared the Trump flair for publicity and self-promotion, dating “Footloose” star Lori Singer and organizing a “Sino-American Real Estate Conference” at The Plaza Hotel to attract Chinese capital that would let him go after bigger properties. On another occasion, Zackson held a $1,000-a-plate fundraiser for then-governor Mario Cuomo.

“I hired airplanes to fly over New York on election day that said ‘Giuliani + Cuomo: Don’t break up the team,” Zackson recalled.

“He just was very bold in the way he’d do things,” said Carolyn Schlam, a Los Angeles-based artist who ran marketing at Dynamic Group back then. “Brad was the best salesman. I was always saying that to him, ‘just be a broker,’ because he could have made so much money as broker, but he wasn’t satisfied. He wanted the limelight.”

Zackson found success as a property manager and supervising conversions of commercial and rental properties to co-ops and condominiums. But like Trump, he fancied himself as a big-league Manhattan owner and developer. In 1994, he acquired a commercial building at 21 Astor Place for $6.3 million in a bankruptcy auction with the aim of converting it into residential condos.

Even as his clout grew, some of the deals he pursued floundered. One of his investors, Jianjun Li, was accused of stealing $10 million from Chinese company SinoChem in order to invest in New York properties with Zackson. Many of Zackson’s projects ended in bankruptcy or selloffs. Those Include The Astor Place site (eventually redeveloped by the Elad Group), 283 West Broadway and Biscayne Shores, a 14-acre parcel near Miami Shores in Florida.

Despite the patchy track record, some partners remember Zackson as bringing a lot to the table. Patrick Morelli, Who Teamed Up With Him On The West Broadway project, said Zackson had access to deal flow, since he knew all the right people.

“You’ve gotta have some kind of leverage,” he said. “If you’re not in the game, you’re not going to ever be in the game. He was in the game — that was worth its weight in gold.”

Views

432 Park Avenue is the skyline-defining cash cow that every developer dreams of building. The skinny supertall towers over Billionaires’ Row on the site of the former Drake Hotel, and its residential condos have a projected total sellout of over $3 billion. But its twisted route to become the symbol of the new oligarchy includes a tryst with Manafort and Zackson.

When Harry Macklowe took control of the Drake site in 2006, he hoped to build the city’s most ostentatious residential project. But his $7 billion overleveraged purchase of seven Equity Office towers unraveled his entire empire. Desperate for a bailout on the Drake site, he struck a deal in 2008 to sell a majority stake to an entity called CMZ Ventures for $850 million.

The “C” in CMZ was Arthur Cohen, an industry stalwart, now deceased, who had long faded into the background. The M and Z were Manafort and Zackson. The trio hoped to create a billion-dollar investment fund targeting distressed U.S. properties, of which there were plenty. The Drake was their biggest prize.

Jiehe and Zackson sit across from each other as tea and Trump Water is served. (Credit: Dynamic Worldwide Group)

Manafort and Zackson were neighbors in the Hamptons, and soon became friends and business associates. Zackson says he invested in Manafort’s film production business, Manhattan Pictures, best known for the 2005 film “The Dying Gaul.” The film, which flopped, is about a gay screenwriter forced to change the plot of one of his works to be about straight people.

Through CMZ, the partners planned to develop the Drake site into a 65-story “Bulgari Tower,” a luxury hotel-condo skyscraper with a private club and a mall with hologramed walls on which retailers could splash their brands. To get the Drake deal over the line, they were counting on one man’s money in particular: Dmitry Firtash, the Ukrainian gas tycoon that Manafort may have met while consulting for Ukraine’s ruling party, the pro-Kremlin “Party of Regions.”

In the fall of 2008, the CEO of Firtash’s company, David Brown, sent a letter to Manafort committing $112 million in equity to the project. The firm put a $25 million deposit into escrow.

The equity for the deal never came together, however, and with time running out, Macklowe needed a savior. Fund manager CIM Group swept in, buying the defaulted debt at a fat discount, and took over the majority equity stake in the project. All told, CIM’s investment was less than half of what CMZ had agreed to pay.

But Firtash’s $25 million deposit became the subject of at least three legal inquiries. First, the former prime minister of Ukraine, Yulia Tymoshenko, alleged in federal court in 2011 that Firtash used CMZ as a front in order to hide income illegally skimmed from his natural gas company RosUkrEnergo. Zackson was named a defendant in the case. Tymoshenko also claimed that Firtash never planned to close on any real estate deals and instead filtered the money back to Europe in order to fund Tymoshenko’s political adversary, Victor Yanukovych, who became president in 2010. (Yanukovych is now in exile in Russia and wanted for high treason in his native country. Firtash, meanwhile, is facing extradition to the U.S. from Austria over bribery charges.)

CMZ also had ties to Oleg Deripaska, an aluminum oligarch with close Kremlin ties: Deripaska, Manafort, and a Manafort associate named Rick Gates formed an investment fund called Pericles, through which Deripaska was set to make a $56 million investment in the Drake, according to court filings. In a memo included in the filings, Gates refers to Deripaska only as “Mr. D.” The U.S. government suspects Deripaska has links to organized crime and denied him a visa in 2008.

Tymoshenko’s attorney, Kenneth McCallion, said that shortly after he filed the now-dismissed suit against Firtash and the Drake team, the U.S. Attorney’s office opened a separate criminal investigation into CMZ, which according to a Bloomberg report has since been transferred to Mueller’s office.

“They [CMZ] had hundreds of companies and bank accounts and got wire transfers in from the Firtash people, supposedly looking at real estate stuff,” McCallion said. “But it ended up being one big money-laundering operation.”

McCallion suspects CMZ never intended to close on any of the deals.

“It’s not strange if you’re basically in the money laundering business — that’s the way to do it,” he said. “You don’t really want to close on deals, [because] then your money is tied up in brick-and-mortar. Whereas if you’re just collecting money for a deal, you can keep moving it around.”

Zackson, though, blamed the Drake miss on bad timing.

Arthur Cohen and Harry Macklowe (Credit: Dynamic Worldwide Group)

“This was nothing more than one of the great deals of New York, that crashed in 2008 when the market fell,” he said. “We worked around the clock for nine months with Harry Macklowe trying to make the deal work as the market collapsed.”

Macklowe did not respond to requests for comment.

According to emails obtained by the New York Observer in 2011, Zackson attempted to get Donald Trump in on the Drake. Zackson denies this and said he had planned to partner with Trump on a different project, at 12-18 West 55th Street. The pair dropped that deal, according to Zackson, because buying out the rent-regulated tenants at the building would be tricky. Representatives for the Trump Organization didn’t respond to requests for comment.

The biggest deals you’ve never heard of

Though it’s Manafort’s ties to Trump that may now be giving Zackson access to the kind of capital he’s been chasing all his life, he’s trying to keep his distance from the scandal surrounding the campaign.

“I worked for Mr. Trump’s father and I have a relationship with Paul, but I have nothing to do with their campaign — nothing to do with any of that,” he said. “I’m more interested in doing my work, you know?”

Zackson said he’s busy putting together a series of extraordinary deals that he describes on his site as “conceptual plans.” His detractors, however, say they are pie-in-the-sky.

On Aug. 24, he said the Chinese firm that Manafort is advising, Pacific Construction Group, is considering partnering with him in a plan to redevelop a giant swath of land, partially owned by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, in Willets Point. The project would include at least one new sports stadium and an “intermodal transit facility,” for the Air Train and long-term parking for LaGuardia Airport, as well as nearly 18,000 units of middle-income and affordable housing. By comparison, Stuyvesant Town-Peter Cooper Village, Manhattan’s largest rental complex, has 11,250 units.

Brad Perkins, a principal at Perkins Eastman, confirmed that his company was working on the project for Zackson, though he admitted his client’s outlook was sometimes too rosy.

Zackson “only has an optimist button on his keyboard,” Perkins said.

A representative for the MTA said it has no requests for proposals out on Queens development sites. Sources said, however, that it’s not uncommon for developers to send in unsolicited proposals.

According to Zackson, Manafort is not involved in the development of the project, though he said Manafort could pocket a consulting fee from Pacific should they choose to invest.

During the July meeting at Perkins Eastman, the group discussed the Chinese company’s aspirations in the U.S., which include potentially acquiring major construction firms and investing in U.S. infrastructure.

When asked if Munilla — the Miami-based construction firm whose principals Jorge and Fernando Munilla are in the photograph with Manafort and Jiehe — was one of the targets, Zackson would only say that Pacific wanted to acquire a Miami-based firm.

Executives from Munilla Construction with Manafort and Jiehe. (Credit: Dynamic Worldwide Group)

If Pacific did buy Munilla, it would put the firm at the helm of a plan to build the Navy school at Guantánamo, a $66 million Pentagon contract Munilla won last year. Pacific’s involvement could attract the attention of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), which reviews foreign investments and assets for national security risks.

According to a June report in Politico, Pacific tapped Manafort explicitly so that it could have access to the Trump administration. Sources told the outlet that a separate Chinese company was interested in acquiring Puerto Rican infrastructure. Manafort, according to Politico, had told an attorney involved that he could get the Trump administration to bless such a deal.

Executives at Munilla did not return multiple calls seeking comment, nor did Pacific.

Another property on Zackson’s radar is the 1,015-room Roosevelt Hotel. Sources said that hotelier Shahal Khan, founder of Trinity White City Ventures, which made plays for The Plaza Hotel and Dream Downtown in 2015, spoke with Zackson several months ago about a potential deal to buy the Roosevelt, which is owned by the Pakistani government through its national airline, PIA.

Khan confirmed he was interested in buying the hotel, and plans to offer north of $500 million for it. He said, however, that neither Zackson nor Manafort is involved in his bid. A spokesperson for PIA could not be reached.

Zackson’s relative anonymity stems from his inability to put money into projects.

“He ran around with a bunch of different partners,” said Andrew Gerringer of the Marketing Directors, a new development marketing firm that consulted on a plan by Maloney’s Property Markets Group and the Hakim Organization to redevelop the Clock Tower in Long Island City. “He was never strong enough to do something on his own, but he always has good ins with the government. He was like the connector – he would find a property and someone else would put up the money.”

In April, Zackson filed a $400 million lawsuit against PMG over the Clock Tower site. PMG and Hakim looked to build a condo-rental tower project, but sold the site to the Durst Organization when they couldn’t score financing.

Zackson was working with Hakim principal Kamran Hakim on the project through an entity called Dynamic Hakim. By selling the site, Zackson alleges, PMG cost him a share of agreed-upon profits from the redevelopment. He described Maloney as a “shim-sham con man.”

“I should be a pretty wealthy guy if it wasn’t for partnering with PMG,” he added.

PMG rubbished his claims, describing Zackson as a “failed and disgruntled former broker who is living beyond his means and who did not invest any money in the deal.” Zackson said he is still involved in another project with the duo, at 42-50 24th Street in Long Island City. (Sources close to PMG disputed this.) Several sources confirmed that Fisher Brothers is now involved in the project.

Zackson’s value, sources said, lies in his tenacity, his ability to navigate zoning restrictions, and perhaps most importantly, his Rolodex of both public officials and private investors. But those who have the funds get to call the shots.

“He gets himself in these situations and doesn’t have any control of them because he has no money,” Gerringer said. “He’s left there with no say in anything. He has to take what he’s given. He’s always out there looking for guys who have money but need some extra piece that he can spin his story to.”

Home improvement

377 Union Street, Carroll Gardens, Brooklyn (Credit: Will Parker)

In 2012, Paul Manafort bought a charming brownstone in Carroll Gardens for his daughter, Jessica. That property, at 377 Union Street, has since become the subject of both state and federal investigations.

At question: a series of mortgages made by the Chicago-based Federal Savings Bank, which is headed by Trump campaign adviser Steve Calk. The loans on 377 Union and two other Manafort-owned properties in the Hamptons and Virginia total $16 million – nearly a quarter of the bank’s total equity capital. Experts told WNYC earlier this year that the loan transactions resembled money laundering. Neighbors have complained that the vacant home is a dilapidated mess.

Sources said that the person handling renovations on Manafort’s behalf was Brad Zackson. Zackson confirmed this.

“I’m just helping a friend out who the world is attacking for no reason,” he said.