Steve Shull, a retired NFL linebacker, has been coaching real estate agents since 1993. He knows from experience that the brokerage business is cyclical: When the market is hot, paychecks are fat. But over the past few years that simple rule no longer seems to hold true.

“This should be high time for agents,” Shull said, “and I don’t think it is.”

Home prices in New York are much higher than they were a decade ago (despite a recent slowdown in the luxury market) and annual apartment leasing volume in Manhattan has tripled, according to appraisal firm Miller Samuel. Yet you’d be hard-pressed to find an agent who thinks the brokerage business is better off than it was a decade ago. On the contrary, Schull said he sees “agents struggling more and more to make a living.”

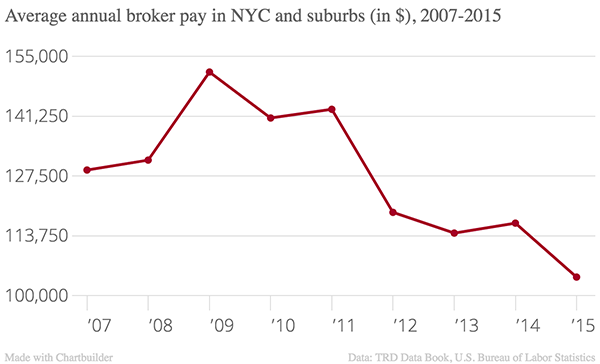

Indeed, average pay for real estate brokers in the greater New York area fell continuously between 2011 and 2015 even as Manhattan sales prices rose, according to data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Other industries, too, are grappling with the paradox of low earnings in a strong market. Media companies, for example, are folding left and right even though more Americans than ever before consume news on a daily (if not hourly) basis. And manufacturing jobs are disappearing even though households buy more consumer goods.

Other industries, too, are grappling with the paradox of low earnings in a strong market. Media companies, for example, are folding left and right even though more Americans than ever before consume news on a daily (if not hourly) basis. And manufacturing jobs are disappearing even though households buy more consumer goods.

The causes are similar. Like factory workers and journalists, real estate agents increasingly struggle to cope with technological advancements and low-cost competition. And insiders say the market is only going to get tougher for brokers.

“Agents who have been in the industry for a while need to work a little harder now,” said Bianka Yankov, a broker and CEO of the Spire Group. “It’s not just hitting us right now. Change has been coming for a while.”

Network pains

When StreetEasy announced in June that it would start charging agents a daily fee for rental listings, it marked a shift in the real estate industry’s power balance. For years, the listing portal helped brokers make money at no cost. But as StreetEasy increasingly took on the job of a traditional brokerage house, it wanted a bigger slice of the cake.

“It’s getting harder for people who come into the [brokerage] business because there’s more transparency,” said David Schlamm, head of the brokerage City Connections Realty. In the past people needed agents to find an apartment. Now they can find anything they want on portals like StreetEasy. That has made it harder for agents to justify their fees.

Listing portals haven’t replaced brokers — and they probably won’t. But they changed the job, at least outside of the luxury market.

In the past, agents were “gatekeepers” who sold access to information, Yankov said. Now they are often “advisors” who help clients navigate information they can access by themselves online. Still a valuable task, but less crucial. So, budget-minded apartment hunters often choose to make do without a broker. Listing agents aren’t immune either, as anyone who has ever haggled down a broker fee after finding an apartment on StreetEasy will be able to tell you.

Will Caldwell, who runs Dizzle, a company that helps agents generate leads, said this shift will hit agents on the low end of the market hardest. “The days of the part-time agent are nearing an end,” he said.

Red menace

Those who still want to hire a broker now have more low-cost options to choose from. The Seattle-based brokerage Redfin, which went public in July and currently has a market cap of $1.98 billion, advertises a 1.5 percent listing fee (as opposed to the usual 3 percent) and its brokers charge lower commissions. The British brokerage Purplebricks has a market cap of around $1.32 billion following its December 2015 IPO and recently expanded to California. It charges flat fees, which it claims can save homebuyers thousands.

While discount brokerages have always been around, what’s new, according to Shull, is that some of these firms are backed by millions in venture funding and have the money and ambition to expand. “It’s a different breed of animal,” he said.

One of the biggest challenges for agents is “articulating worth,” Shull said. Why should people hire a broker if they can find apartments on StreetEasy? And why should sellers pay a 3 percent fee if Redfin only charges 1.5 percent? Those who don’t have convincing answers to these questions will have to lower their own prices sooner or later, or leave the business.

One of the biggest challenges for agents is “articulating worth,” Shull said. Why should people hire a broker if they can find apartments on StreetEasy? And why should sellers pay a 3 percent fee if Redfin only charges 1.5 percent? Those who don’t have convincing answers to these questions will have to lower their own prices sooner or later, or leave the business.

“Every agent should understand that this market is changing,” Shull said. “It’s a real wake-up call.”

Schlamm said he encourages his agents to attend more training programs. “We used to hold and guard the information,” he said. “We don’t anymore. So we have to add more value.”

The Million-Dollar-Listing effect

History may remember March 7, 2012, as a turning point for the brokerage business. It was the day Bravo TV’s “Million Dollar Listing New York” premiered. The reality show and its witty protagonists helped change the image of the real estate agent. Once seen as a low-brow gig for bored divorcees, it was suddenly a prestigious job. Who wouldn’t want to gallivant around Manhattan in a snazzy suit and make millions? Best of all, you don’t need a Wharton degree or a perfect GPA.

Industry sources credit MDLNY and similar shows for helping to swell broker ranks in recent years. The Great Recession also helped, Yankov said. As more people found themselves unemployed, working as a broker seemed like an easy way to make a few bucks.

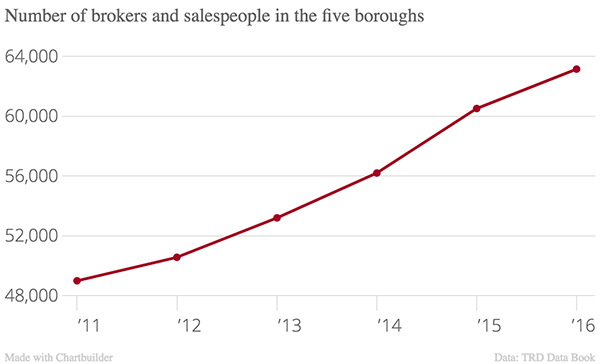

Whatever the causes, the trend is clear. As of 2016 there were 63,142 brokers and salespeople in the five boroughs, according to The Real Deal’s Data Book, up almost 20 percent from 53,193 in 2013. During the same period, the number of Manhattan new apartment leases increased to 55,758 from 45,606, according to Miller Samuel, but the number of sales transactions (which tend to be far more lucrative for brokers) fell to 11,459 from 12,735. In other words: there are more brokers fighting over each listing. And it doesn’t help that a few large, well-connected firms have been hogging new development exclusives.

Whatever the causes, the trend is clear. As of 2016 there were 63,142 brokers and salespeople in the five boroughs, according to The Real Deal’s Data Book, up almost 20 percent from 53,193 in 2013. During the same period, the number of Manhattan new apartment leases increased to 55,758 from 45,606, according to Miller Samuel, but the number of sales transactions (which tend to be far more lucrative for brokers) fell to 11,459 from 12,735. In other words: there are more brokers fighting over each listing. And it doesn’t help that a few large, well-connected firms have been hogging new development exclusives.

This increase in competition, combined with the spread of online listing portals and discount brokerages, has led to “broker commission compression,” said Andrew Heiberger, CEO of Town Residential. Lower pay and job insecurity weigh on people. “There is broker anxiety,” he said.

What does all this mean for the future of the business? Sources interviewed for this story predict that the brokerage industry of the future will be smaller than it is today.

“There’ll be a lot of people exiting the field if they can’t make a living,” Schlamm said. “A good broker will always do well,” while the typical broker gets “punched around pretty bad.”

Success depends, he said, on a simple question: “How well can you take a punch?”