In 2011, three weeks before construction of the Chateau Louis XIV would finish, celebrity real estate broker Jeff Hyland spent half a day touring Emad Khashoggi’s magnum opus on the outskirts of Paris. He came away impressed by the development’s splendor and attention to detail, but also a little baffled.

Sitting on a 57-acre park a short drive from Versailles, the mansion is built in the style of a 17th-century palace: gold-plated water fountains and marble statues outside, grand staircases and elaborate chandeliers inside. Also included: a nightclub, a movie theater, a moat doubling as an aquarium and two downstairs lounges. As Hyland understood it, one lounge was for men and the other for women. The design didn’t seem like it would appeal to his rich American clients.

“I was racking my brain. Who could I have for it?” the Los Angeles-based broker recalled. In hindsight, he said, the answer was obvious: “[Khashoggi] must have known up front that he’d be selling it to a Middle Easterner.”

The guy just — for lack of a better term — has huge balls and put them on the table.

Four years later, in December 2015, the property sold to an unnamed buyer for around $300 million. It was reportedly the most expensive home sale in modern history. Last month, the New York Times reported that the mystery buyer was Saudi Arabia’s crown prince Mohammed bin Salman. It was a terribly embarrassing revelation for the crown prince, who’s leading a so-called anti-corruption campaign against the elites of Saudi Arabia and was also recently outed as the buyer of a record-breaking $450 million Leonardo da Vinci painting.

Almost a century after the Treaty of Versailles, a French palace is a conversation topic in diplomatic circles again. Its developer, who happens to be Dodi Fayed’s cousin and the nephew of the world’s most infamous arms dealer, is receiving much less attention. While other builders of luxury homes, such as the Candy brothers, are masters of self-promotion, Khashoggi is a bit of an enigma.

“His brand is nonexistent other than this anomaly,” said Cody Vichinsky, co-founder of the luxury brokerage Bespoke Real Estate. “This sale put him on the global map.”

Real estate royalty

Khashoggi was born in Lebanon into an illustrious Saudi family of Turkish descent. His grandfather served as the first Saudi king Ibn Saud’s court doctor. His father, Adil, made a name for himself in the early 1970s as one of the owners of Triad along with his brothers Essam and Adnan. The holding company had interests in meat canning, oil, real estate and marketing ventures around the globe, according to Peter Hobday’s book “Saudi Arabia Today.” Eventually Adnan bought out his brothers, who each held 20 percent stakes, according to Ronald Kessler’s “The Richest Man in the World.”

Adil became a real estate developer. Adnan’s life took a very different turn: he became a billionaire selling American-made weapons to Middle Eastern countries. At the height of his wealth, he owned a 282-foot yacht (which made a cameo in a Bond film and later sold to Donald Trump) and 12 properties (including a 180,000-acre ranch in Kenya and a two-story apartment at Olympic Tower in Manhattan).

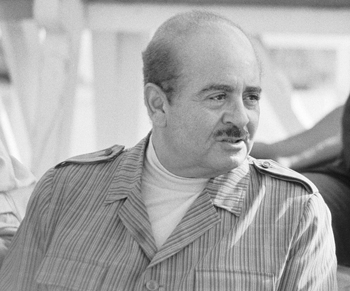

Adnan Khashoggi

Famous for hosting extravagant parties and married three times, Adnan liked people to believe that he was the richest man in the world, even if he wasn’t. “For A. K., there were no laws, no skies, no limits,” Prince Alfonso Hohenlohe-Langenburg of Spain told the Times. His empire began to unravel in the late 1980s amid the Iran Contra scandal and allegations that he helped Philippine dictator Ferdinand Marcos hide his real estate investments, which included the Crown Building, 1 Herald Square, 40 Wall Street and 200 Madison Avenue. By the time of his death in June 2017, Adnan had lost much of his money.

Adil was his brother’s “opposite in almost every respect,” Kessler wrote. He remained married to his first wife and eschewed the jet-set life, spending much of his time in the Saudi capital, Riyadh.

Adnan and Adil had a sister, Samira, who married Egyptian billionaire Mohammed Al-Fayed. Their son Dodi dated Britain’s Princess Diana and died alongside her in a car crash in 1997.

The Road to Versailles

Like his father and uncle, Khashoggi went to college in California, graduating from Pepperdine University in 1987. Two years later he launched his development company, COGEMAD, in Cannes.

The firm’s first major project was the restoration of La Tropicale, a Cannes mansion dating back to the turn of the 20th century. In 1999, he began renovating another turn-of-the-century mansion, the Palais Rose near Paris. And more recently the company, now headquartered in a Paris suburb, built the Palais Venitien in Cannes. The home, supposedly inspired by Byzantine and old Venetian architecture, was on the market for $124.6 million.

Khashoggi got the idea for the Chateau Louis XIV around 2000, he told the French business news magazine Entreprendre. In 2009, he bulldozed a 19th-century castle in the town of Louveciennes and began construction. About 150 artisans worked on the project for more than two years, according to Entreprendre. The challenge, Khashoggi told the outlet, was “to combine the best in home automation with current building standards and architectural rules from another century over thousands of square meters — and all in two and a half years!”

[Khashoggi] must have known up front that he’d be selling it to a Middle Easterner.

The finished product looks like a 17th-century castle, except it isn’t. Electric elevators shoot up and down. Water fountains and air conditioning can be controlled by phone. Khashoggi also built an underwater lounge with transparent walls and ceilings into the moat.

COGEMAD did not respond to several requests for an interview.

Every single detail in the building looked expensive to Hyland. “There was nothing in it where corners were cut,” he said.

Like Gary Barnett with his One57 condominium project in Manhattan, Khashoggi timed the market well. As the world recovered from the Great Recession and central banks pumped money into economies around the globe, the ranks of the super-rich grew. So did the demand for luxury real estate.

But Chateau Louis XIV was still an extremely risky bet. “The guy just — for lack of a better term — has huge balls and put them on the table,” Vichinsky said. The danger, he said, lay in the mansion’s “taste-specific” design.

Plenty of people want to look down on Central Park, but few want to look up at the underside of a sturgeon from the comfort of a white, ring-shaped couch in a fake 17th-century palace — especially if the privilege costs $300 million.

“If you saw [Chateau Louis XIV] here in the U.S., you’d say, ‘Oh that’s Las Vegas. That’s so cheap. That’s so corny. That’s someone’s lottery earnings,’” said a luxury real estate broker, speaking on condition of anonymity.

To Vichinsky, Khashoggi placed an all-or-nothing bet and won. Either there was no market for his project and he was completely screwed, or there was one and he had it cornered by default.

“If that guy wants it, he has nowhere else to go,” Vichinsky said, referring to bin Salman. “But he could be one of two people on the planet.”