Once upon a time, a brash attorney became New York’s mayor and saved the city from crime. Now that the mean streets weren’t so mean anymore, young, wealthy, white people discovered the city was the promised land. So they flocked from the suburbs to Manhattan and prime Brooklyn, frequenting brunch spots, inventing apps, doing yoga, gentrifying neighborhoods and living happily ever after.

That, at least, is how the fairytale of the 1990s goes. The other, demographic story of New York’s revival lacks a hero, is a lot less romantic, and may not have a happy ending for real estate owners and developers.

It begins in 1990, when the number of births in the U.S. reached a 20-plus-year high. Rising birth numbers coincided with a spike in immigration to create the largest and most educated generation in the country’s history, eclipsing even the baby boomers.

As the first millenials graduated from college in the early 2000s, they did what educated young people in search of well-paying, fulfilling jobs had done in the 70s, 80s and 90s: move to the big city. Now, however, there were a lot more of them.

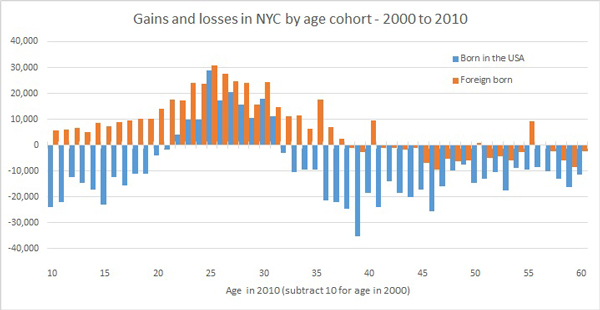

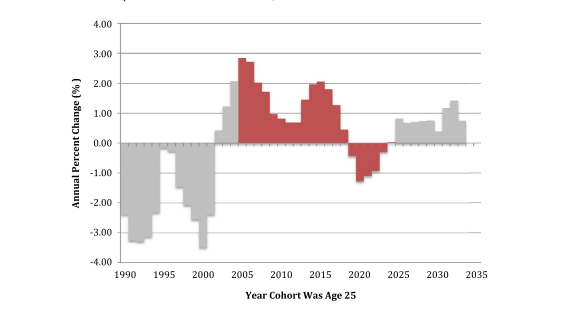

Between 2000 and 2010, the number of twenty-something New Yorkers exploded (see chart above), helping the city add a net 234,000 residents. This trend coincided with broader demographic changes(see chart below): the number of people in their twenties across the U.S. also grew at historically high rates during that period, according to Dowell Myers, a professor of urban planning at USC. Population growth boosted the economy and pushed up rents in New York, San Francisco, Seattle and other urban centers. It enriched landlords and often displaced low-income residents.

The rise of the knowledge economy, cultural changes and declining crime rates also helped cities grow. But demographics played a major, often underappreciated, part.

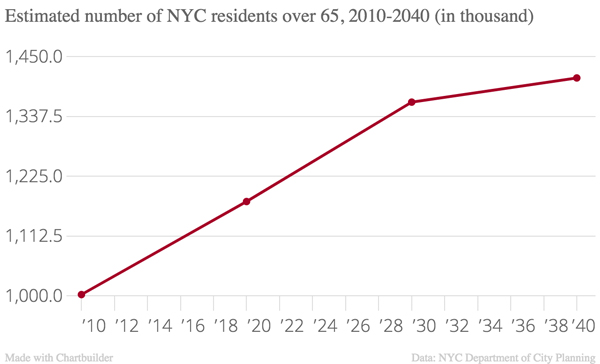

This long demographic growth cycle is now over. Myers estimates that the number of 25-year-olds in the U.S. peaked in 2015 and will start falling in the coming years. And the population is aging. The impact on New York City — and its real estate market — could be profound.

Youth exodus

“Urban America is definitely having a good run here,” the Blackstone Group’s Jonathan Gray said during an October interview with Yahoo Finance.

The reason, according to America’s largest private landlord? Millennial tastes.

“Millenials are saying: no, I want to be in an urban environment,” Gray said. “I want to be able to get a latte, I want to be able to ride my bike (…) and so you’re seeing the companies react.” Gray subscribes to the industry’s current mantra: a property’s worth is measured mostly by whether or not it appeals to young people.

But will that change as New York ages? In a 2016 paper, Myers argued that millennials, like generations before them, tend to move to the suburbs as they grow older and more affluent. And not only that. “Whereas the demographic pipeline pumped young adults into cities at full volume, the normal turnover and outflow was clogged by older peers who lacked the job and housing opportunities” to move up the social ladder and into the suburbs in the wake of the Great Recession, he wrote. Now that the economy has improved, more older people may choose to leave the cities as well. Plenty of people didn’t ditch the minivan and backyard dream because they love living in a cramped Brooklyn apartment — they ditched it because they couldn’t afford it.

If an inflow of the young boosted urban economies and increased property values, an outflow may do the opposite. Demand for apartments could fall, as could rents. The economy may suffer, which would also hurt the commercial real estate market. In a 2016 paper, three economists from Harvard and the RAND Corporation estimated that an aging population alone will slow U.S. economic growth by 1.2 percentage points over a decade.

New York may also be left with thousands of live-work-play studio apartments nobody wants. The recent multifamily construction boom was all about millennials, featuring smaller apartments and bigger gyms. If Myers is right, demand for these units will fall.

Other researchers argue the number of millennials won’t actually fall, but plateau. Urban economist Joe Cortright argues that young professionals increasingly want to live in cities. “More young adult urban growth is coming,” he concluded.

For the moment, the numbers appear to be on Myers’s side. Census data released in March showed population growth in downstate New York falling by half between 2015 and 2016.

Bye, bye pension money

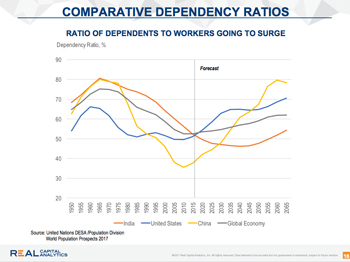

We may not be sure if New York’s overall population will keep growing, but this we know: pension funds are in trouble. In the U.S., the European Union, Japan and China, populations are aging. Fewer people are contributing to the pension system while more old people are slated to receive fat retirement packages. A recent report by the Hoover Institution found that U.S. public pension funds’ unfunded liabilities grew by $434 billion between 2014 and 2015 alone, to $3.84 trillion.

Shrinking pension contributions mean funds have less money to invest.

“So much of the institutional money coming to our sector is from state public pension systems that are underfunded,” said Real Capital Analytics’ Jim Costello.

An affiliate of Ontario’s public pension fund OMERS is a co-developer of Hudson Yards. Mitsui Fudosan, which pulls in a significant chunk of its money from Japanese pension funds, is a major player in Hudson Yards and a co-developer on some of its buildings. California’s CalPERS bought $2.7 billion worth of New York City properties over the past five years, according to RCA. But the true extent of the real estate industry’s dependence on pension money is hidden: most funds invest as limited partners or buy into real estate investment vehicles managed by firms like Blackstone.

Both Germany and South Korea have emerged as key investors in the New York real estate market in recent years.

In an October paper, Will Denyer, an analyst at investment research firm Gavekal, wrote that

“Germany will decline as a capital provider after 2030, but China is likely to ramp up quite a bit over the next 10 years, and along with Russia and South Korea will remain an important net provider of capital until 2040. After that, aging will take its toll and these countries’ propensity to save and export capital will decline.”

Interest rates

Interest rates are a big deal for the real estate industry. Low rates make mortgages cheap and other assets (like bonds) look less attractive, increasing investment and pushing up property values.

Pretty much the worst scenario imaginable for the real estate industry is rising interest rates combined with slowing economic growth. With an aging population, that exact scenario might play out.

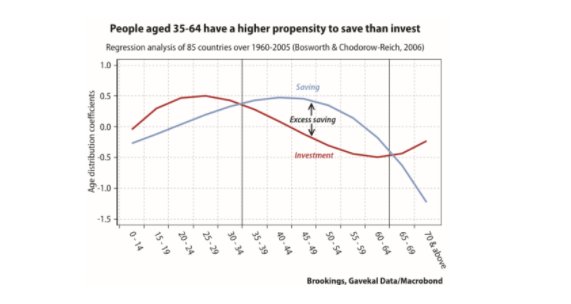

In a nutshell, interest rates are determined by supply and demand for credit. The supply of credit depends on savings rates: if households and companies deposit more money with banks or pension funds, these institutions can lend more at lower rates.

Between 1990 and 2016, rising life expectancy helped keep interest rates low, according to a recent letter by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. People knew they’d likely live longer, so they saved more, increasing the supply of credit in the economy.

But in the coming decades, this dynamic could reverse itself. Gavekal’s Denyer argued that as a bigger share of the population reaches retirement age and starts spending their savings, the supply of credit will shrink and interest rates will rise.

“A very old population, like a young population, sees its propensity to save fall below its propensity to invest,” he wrote. “Capital must be borrowed from other countries or, if it is a global phenomenon, the real rate of interest must rise to bring savings into equilibrium with investment. This is the situation the world will find itself facing from roughly 2027 onward.”

Read more from The Long View here.