From the March issue: It might sound unglamorous, but back-end listing systems for residential firms are the startup world’s latest meal ticket.

Long the domain of two companies in New York — RealPlus and On-Line Residential —the space is being upended by new tech startups with venture money to burn.

“In the past, a listings platform was enough,” said Michael Gabriel, founder of Gabriels Technology Solutions, which works with real estate firms. “Today to be competitive, a solution has to be much more.”

That shifting landscape is the result of several factors — from better access to data to advances in technology. While numbers are hard to come by, the space is clearly a lucrative one.

For the vendors — most of which make money by selling subscriptions to their services —the financial opportunity is big. And they are aggressively trying to lock in clients by touting their sophisticated analytics and slick mobile apps. All of this, they claim, will boost agents’ business in a competitive market.

And they are already making waves.

In February, RealPlus suffered a blow when a major client — Sotheby’s International Realty — decamped for Perchwell, a year-old rival.

The shakeup came less than a year after the Real Estate Board of New York rolled out a syndicated feed of its residential listings, known as the RLS. That move opened the door for both consumer-facing sites and vendors to rush into the space with newfound access to the city’s residential listings.

The shakeup came less than a year after the Real Estate Board of New York rolled out a syndicated feed of its residential listings, known as the RLS. That move opened the door for both consumer-facing sites and vendors to rush into the space with newfound access to the city’s residential listings.

“Firms are going to be relying on people like us less and less,” acknowledged Eric Gordon, founder of RealPlus, which is overhauling its offerings to keep up.

Gabriel said these cutting-edge platforms are in greater demand now because firms are using them to woo top agents. “The more tools that a brokerage firm can offer agents that are going to help them sell, drive revenue and drive leads, that’s an advantage over another firm,” he said.

In New York, the city’s largest firms — the Corcoran Group and Douglas Elliman — have historically relied on their own proprietary systems, dubbed Taxi and Limo, respectively, to manage listings. But last year, Elliman tapped StreetEasy to build it a new back-end system.

But not everyone is comfortable with that kind of outsourcing.

But not everyone is comfortable with that kind of outsourcing.

For example, the Zucker Organization, which until recently used OLR and Nestio to push listings out to brokers, launched a website last month that feeds listings directly to StreetEasy and the RLS.

Laurie Zucker said her main concern was maintaining control of the company’s listings, especially since StreetEasy now charges $3 per day to post rental listings. (Zucker’s management subsidiary, Manhattan Skyline — which oversees the new website — may decide, for example, to feed only some of its listings to the site.)

“We’re being bombarded by people who want to charge lots of money to do things,” she said. “I’d rather be in control of what our costs are and how listings look.”

Still, there are plenty of landlords and brokers willing to shell out for these services.

“By and large, people don’t want to be in the technology business, but they want to use technology to do better business,” said Caren Maio, co-founder of Nestio, which is geared toward the rental market.

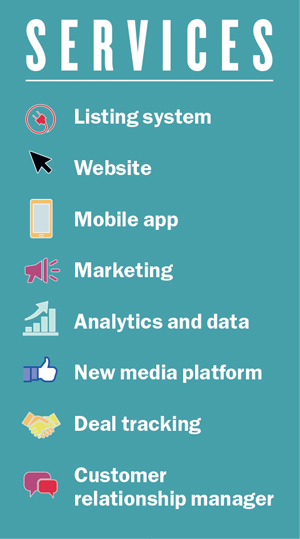

Below is a rundown of the main players in the sometimes-complicated, quickly evolving space of listings software.

Founded in 1987, RealPlus was the first company to enter New York’s residential listings game at a time when brokers shared listings via fax or snail mail.

Founded in 1987, RealPlus was the first company to enter New York’s residential listings game at a time when brokers shared listings via fax or snail mail.

Using IBM software, RealPlus began to streamline that process by building listings databases for firms. Then once a day, companies would fax their updated listings to a distribution list made up of other firms.

The service was valuable enough that in 2001, Terra Holdings — parent company to Brown Harris Steven and Halstead Property — bought a 50 percent stake in the company.

In 2002, RealPlus overhauled its business when it launched a shared electronic listing exchange dubbed R.O.L.E.X. to pipe listings between REBNY’s member firms. (R.O.L.E.X. was free, but firms paid for interfaces like RealPlus and OLR to access those listings.)

Now, if a broker at one firm entered a listing into the system, agents at other firms would be able to quickly access it and start showing it to buyers.

But in 2013, REBNY tapped Katonah, New York-based Stratus Data Systems to launch the RLS — replacing R.O.L.E.X. with a newer model.

The changeover was rocky.

Five years later, R.O.L.E.X. still exists, but it’s not partnered with REBNY so it’s only used by RealPlus clients, who are charged roughly $100 to $150 per month for each of their agents, Gordon said. And, it sends its clients’ listings to the RLS, which then feeds those listings industrywide.

But as the environment has grown more competitive in the last year, Gordon has hired more engineers and designers, doubling his staff to around 17. He’s also updated his offerings with mobile apps and other tools.

“We’re forced to do what we have to so we can compete,” he said.

Before last month, its four largest clients were BHS, Halstead, Stribling & Associates and Sotheby’s. But Stribling and Sotheby’s have since jumped to Perchwell, while BHS stopped using RealPlus and instead had Gordon build it a proprietary system called Resource. (Citi Habitats, which once used RealPlus to help manage rental listings, moved that job in-house last year.)

“There are changes that are coming, for sure,” said Gordon. “We have to come up with other ways of keeping relevant.”

RealPlus has, for example, added features to its system to ensure that the RLS (and aggregators) have real-time updates to listings.

“It used to be OK for a listing to be entered at 1 p.m. and show up on syndication sites at 5 p.m.,” said Gordon. “Not anymore.”

OLR wasn’t first on the scene, but it was the first to offer an electronic platform for sharing residential listings when it debuted in 1995. Back in the days of dial-up modems, founder Jonathan Greenspan, a former commercial broker, said he had five computers lined up on a desk, and firms would log in starting at 6 a.m. each day to download new listings.

OLR wasn’t first on the scene, but it was the first to offer an electronic platform for sharing residential listings when it debuted in 1995. Back in the days of dial-up modems, founder Jonathan Greenspan, a former commercial broker, said he had five computers lined up on a desk, and firms would log in starting at 6 a.m. each day to download new listings.

Prior to that, he said, “Not only was there no vehicle to share listings among a cooperating pool of brokerage firms, but many firms — particularly the larger, more established ones — saw no need to co-broke.”

Greenspan said OLR’s mission since launching has been to offer standardized, clean data to brokerages of all sizes.

Despite new rivals vying for market share, brokerages have continued to pay to play ball with the 50-person company, which has a 7,000-square-foot office in the Financial District. While Greenspan declined to disclose market share data, he said about 12,000 New York agents use OLR. Clients include major firms such as Compass and Halstead Property, which pay to access one of its most valuable offerings — its deep well of historical data. (TRD also uses it regularly to analyze listings information.)

In addition to managing listings and sending them into the RLS, OLR lets clients track deals completed by a firm, office, team and agent. It’s a feature others (like Perchwell) also offer, but OLR has beefed up its development team in response to the competition and plans to roll out a new media platform for uploading photos, floor plans and video for listings. And it recently introduced a mobile listing tool with the option for real-time push notifications, among other features.

“An agent can enter a new apartment, take pictures with their phone, write some copy and have the listing on their website within minutes,” Greenspan said.

According to Greenspan, syndication of the RLS hasn’t impacted OLR’s business. “Markets always have new entrants,” he said, though he added that he believes the space is “cluttered” with too many information sources.

Still, the free market breeds competition, and that’s pushed everyone to improve product development — himself included: “If I stood still, I’d be out of business.”

With competition intensifying, he said, OLR has hired additional programmers and is upgrading products in the development queue. Although OLR lost a “few clients” to Nestio early, Greenspan said the attrition was because the startup was a “new shiny wheel.”

“None of these new entrants have a sliver of the experience offered by OLR,” he said.

While OLR and RealPlus catered to the sales market, listings platforms for the rental market pretty much languished until 2011. That’s when Caren Maio and Mike O’Toole launched Nestio to address what Maio described as a “gaping opportunity” to bring modern technology to property owners and brokers who were manually tracking and managing rental listings.

While OLR and RealPlus catered to the sales market, listings platforms for the rental market pretty much languished until 2011. That’s when Caren Maio and Mike O’Toole launched Nestio to address what Maio described as a “gaping opportunity” to bring modern technology to property owners and brokers who were manually tracking and managing rental listings.

“The incumbent was pen and paper, spreadsheets and people trying to utilize a database that wasn’t built for this segment of the market,” Maio said.

In 2015, Nestio raised an $8 million Series A round led by Trinity Ventures. What started as a tool for tracking rental inventory for landlords and owners now includes data, marketing, website and listing distribution services.

Today, the 30-person firm works out of a 6,000-square-foot Flatiron office where the main conference room doubles as a cantina and a birch-tree wall divides communal space from workspaces.

In July, Nestio began offering custom websites, including a scheduler tool that lets potential renters book an appointment to see an apartment. (On the owner side, clients include Two Trees Management and Olshan Properties, while on the brokerage side Compass, Keller Williams and Mirador Real Estate have signed on.)

Nestio estimates that it works with 10,000 agents citywide. Maio said the landscape in New York has changed, and one of the biggest needle-movers was StreetEasy’s $3-a-day rental charge. That added cost, she said, has prompted landlords and agents to reevaluate tools to help rent apartments most efficiently.

Maio said her clients are clamoring to stay ahead of the competition, which is at an all-time high thanks to the new development boom that dumped thousands of rental units on the market.

Nestio declined to disclose its financials, but like other vendors it derives revenue from subscribers — landlords and brokers — who pay a monthly fee that’s based on which services they use. Brokerages can use Nestio in two ways. Some rely on its listings database to access RLS inventory and input exclusives, which Nestio feeds to the RLS and other aggregators. Others — who may have their own platform — use its marketing and data services to analyze comps or get market information derived from the firm’s listings database.

“Our pitch to big brokerage firms who have their own system is, ‘We have the majority of the rental data on the market. We can pipe it into your database,’” she said.

Maio said the industry is turning a corner. “People are now starting to lean in and say, ‘How do I know if what I’m doing is working?’” she said. “That’s the next level of opportunity for companies like mine to provide insight there to say, ‘This is what’s working.’”

Since its debut last year, Perchwell — which bills itself as a one-stop shop that combines listings, analytics and marketing — has racked up a slew of big-name clients.

Since its debut last year, Perchwell — which bills itself as a one-stop shop that combines listings, analytics and marketing — has racked up a slew of big-name clients.

In addition to Sotheby’s and Stribling, those clients include CORE, Warburg Realty, Berkshire Hathaway HomeServices, Fox Residential and Sloane Square.

Founder Brendan Fairbanks, a 31-year-old former investment banker, came up with the idea for Perchwell after an ill-fated apartment search. To date, he’s raised $4 million in seed funding.

According to Fairbanks, StreetEasy and Compass have changed the way NYC residential firms view data and technology, giving Perchwell an opening.

The startup — which only sells subscriptions to firms (not individual agents) — allows clients to created branded market reports on smartphones and then instantly send them to clients. In addition to historical sales, data also included development permits and geospatial data. Fairbanks said he doesn’t consider OLR and RealPlus competitors. “We’re offering a different product,” he said, arguing that Perchwell’s focus is on enhancing data and helping agents interact with clients.

Doug Heddings, CORE’s executive vice president of sales, said he tested the beta version of Perchwell and worked closely with Fairbanks to fine-tune the platform before switching from RealPlus in August.

According to Heddings, agents must often tap multiple platforms — StreetEasy, OLR, RealPlus and even PropertyShark — to search for listings, scrutinize contract activity, crunch the numbers on closed sales and interact with clients. Over the years, he added, some vendors became “complacent” in their offerings. “I don’t want to pretend the market is efficient yet,” Heddings said. “If you compare the New York City real estate market to the rest of the country, we’re archaic.”

But, he said, startups are “definitely moving us in the right direction.”

StreetEasy is best known for being the go-to site for New York City apartment-seekers, but last November, the Zillow-owned portal dipped its toe into the listings-management game when it agreed to build Elliman’s back-end system.

StreetEasy is best known for being the go-to site for New York City apartment-seekers, but last November, the Zillow-owned portal dipped its toe into the listings-management game when it agreed to build Elliman’s back-end system.

The firm will roll it out this spring, said Elliman President and COO Scott Durkin. “Agents will enter their listing one time only, and it will be sent everywhere in seconds,” he said.

Elliman was in the process of overhauling (or replacing) Limo for somewhere between $2.5 million and $5 million when it opted to partner with StreetEasy, Durkin explained. “Our agents demand instant access in a very quick environment on their mobile devices to make it through their day,” he said. “We could never build what we’re getting.”

He said agents using StreetEasy’s platform will access the same homepage as consumers but will have access to several additional folders where they can enter listings, produce comp reports or run market analyses.

StreetEasy — which is run by Susan Daimler in New York — said it has no plans to market its services to other firms. But for Elliman agents, it will also provide stats on how many people viewed their listings (and when) and what properties are trending. “Agents can compare their listing to others in the neighborhood,” Durkin said.

Those tools will rely on historical data that StreetEasy has been collecting since it launched. “We realized that we needed to stay in our lane and sell real estate, and not get distracted with technology and thinking we could build it,” Durkin said. “By the time we’d build it, we’d be obsolete.”