From the outside, the demolition of 270 Park Avenue will look like a painfully tame round of Jenga. Inside, crews will meticulously tear apart 60 years worth of history.

JPMorgan Chase plans to knock down its Midtown East headquarters to make way for a new, 70-story office tower that will span an impressive 2.5 million square feet. The new building will be the first to take advantage of the district’s rezoning, which was approved in August and will allow for roughly 1 million more square feet than the current structure. The destruction of the current 52-story building is believed to be the world’s largest voluntary demolition — a feat made more impressive by the fact that it’ll take place in the heart of one of the densest office markets in the world.

270 Park Avenue

The Real Deal spoke to a number of experts in demolition and interior construction to break down how JPMorgan will systematically remove a notable building from the congested skyline.

As a rule, crowded urban areas don’t typically allow the use of explosives or wrecking balls to demolish a building. Recent implosions took place in roomier locales: The remaining parts of the old Kosciuszko Bridge were cleared away in a controlled explosion in October. In 2013, a 45-year-old, 11-story building on Governors Island was rapidly destroyed via explosives. Across the Hudson River in 2015, three rental buildings in Jersey City were dramatically imploded. But the demise of JPMorgan’s headquarters will be more subdued.

“Whenever you mention demolition to anyone, they think you’re going to use dynamite or other explosives,” said Adam Stock, a project engineer for Howard I. Shapiro & Associates, a demolition consulting company. “It’s more about how you systematically deconstruct the building from the top down.”

Chapter 33 of the city’s building code is a demolition contractor’s “bible,” said Luis Valderruten, a structural engineer with Breeze Demolition. The law spells out how to take apart a building piece-by-piece and the various precautions required along the way.

First, the city’s building code requires owners to remove or contain harmful substances before demolition begins. Once that’s done, the building will be completely enclosed with netting to contain the site (scaffolding is also often used, but due to the Park Avenue tower’s height, a cocoon system is a more likely choice here). All windows will be removed, along with fixtures, skylights and doors. From there, floors are disassembled from the top down. Mini-excavators, along with handheld tools, are used to break up the concrete slabs. Contractors have also employed demolition robots to take on this role (AECOM Tishman did it at 30 Hudson Yards) but the technology remains a rare feature of jobs in the city. Acetylene torches are used to cut apart steel beams and framing, and structural columns — which are the last to be removed — will be broken into smaller pieces.

“It’s a reversal of building a building,” said Borys Hayda, managing principal at DeSimone Consulting Engineers. “It’s a detailed process. It’s not just let’s get some hammers and start ripping it apart.”

Debris is removed from the floors using chutes, hoists or cranes, as well as carts and dumpsters, experts said. Because storage of the crane will likely prove problematic for long stretches of time, the contractor will likely try to remove as much debris without one. The building code specifically states that structural material should not be “thrown or dropped from the building” and leaves the removal method up to contractors and/or structural engineers.

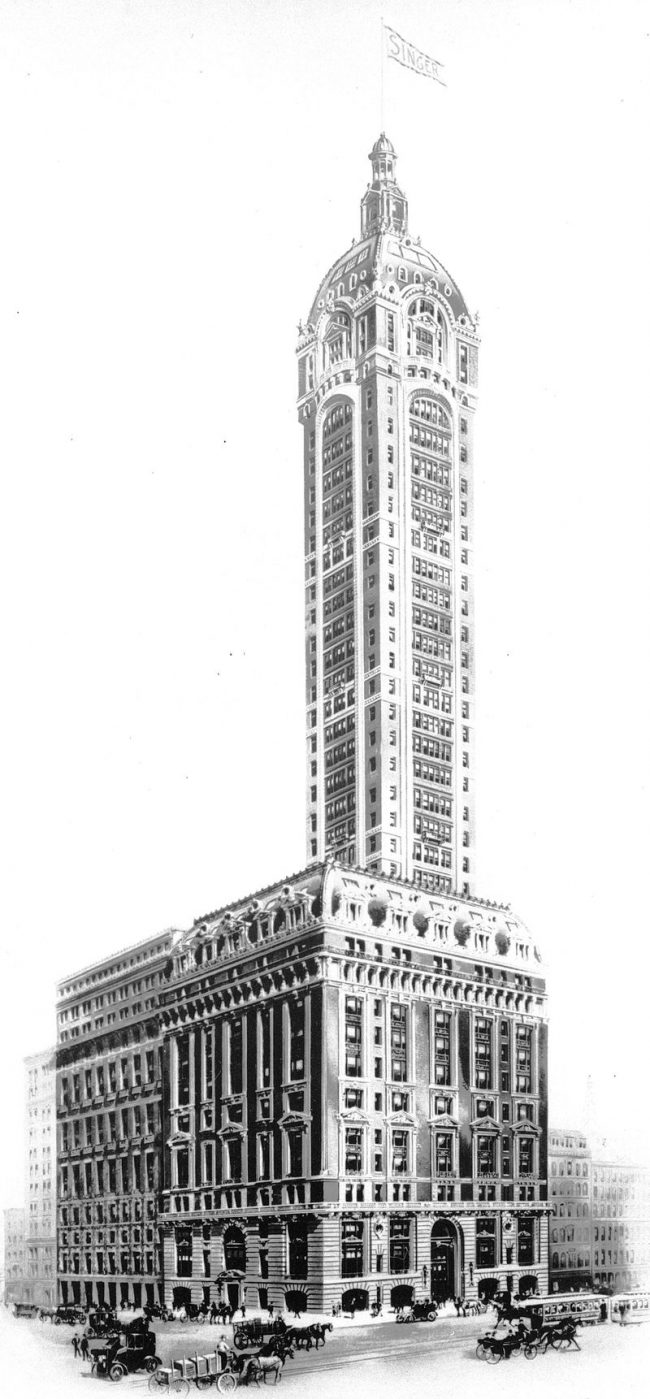

The Singer Building

“The building code gives you several options,” Valderruten noted. “There are many ways to skin a cat.”

Stock said it takes about a week to take apart each floor, though contractors will probably aim to work at a faster pace. So, for the Park Avenue tower, it’ll likely take roughly a year for the building to disappear.

Until now, the tallest building in the world to ever intentionally be razed was the Singer Building, a 612-foot tall tower constructed in 1908, according to the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. It was taken down in 1968 to make way for One Liberty Plaza. The second-largest building to be dismantled in New York City was the former Deutsche Bank Building at 130 Liberty Street. That demolition faced a series of delays over the course of six years and cost $160 million, according to the New York Times. The project was stalled in 2007 by a fire that killed two firefighters. The incident inspired a rule change, in which standpipes and fire safety systems must be maintained during demolition.

Other considerations in the case of the Park Avenue tower will be its proximity to the Metro-North rails and the removal of harmful materials, such as asbestos. A 1957 New York Times story about the tower’s construction notes that the workers were “ankle-close” to the third rails and that to insulate the tower from the train’s vibrations, asbestos-lead mats were used at the base of the supporting columns in the foundations.

Andrew Gray, a spokesperson for JPMorgan, indicated that the bank has not yet hired a company for the demolition work nor a general contractor to handle the new tower’s construction. He declined to discuss the demolition further. Construction is expected to begin in 2019 and take roughly five years. During demolition and construction, many of JPMorgan’s New York employees will work out of L&L Holding Company’s 390 Madison Avenue. The bank just inked a lease for nearly 440,000 square feet at the building.

270 Park Avenue

JPMorgan completed a renovation of 270 Park Avenue in 2011, boasting at the time that the revamp was the largest to achieve LEED Platinum status. Some critics have noted that the company’s energy-saving pedigree is sullied by its decision to scrap a building it so recently gut-renovated. It’s unclear if the company plans to recycle materials from the tower. Hayda said it’s likely that the company will at least recycle the steel and concrete.

“The thing is, putting it in a landfill costs money, so if you can reuse it, sell it or give it to someone for free, you’re still coming out ahead,” he said.

Gordon Bunshaft and Natalie de Blois of Skidmore Owings & Merrill designed the tower, which was completed in 1961 and was then known as the Union Carbide Building. In a 1960 review, New York Times critic Ada Louise Huxtable called the tower “strikingly masculine,” an “impressive” but less-attractive presence in the district when compared to neighbors like the Lever House or the Seagram Building. Those two buildings attained landmark status, but the Union Carbide — along with a few other post-war buildings in Midtown East — remain vulnerable to the (figurative) wrecking ball.