Among the many skyscrapers sprouting up along “Billionaires’ Row,” there is one that’s technically not a new building at all. JDS Development Group and Property Markets Group’s skinny condo project at 111 West 57th Street is classified as an alteration of the Steinway Hall building – an alteration that adds 300,000 square feet in floor space and 66 additional stories.

That project, and many others that the New York City Department of Buildings has officially categorized as alterations, highlights the technical intricacies of determining what counts as a “new building” – a definition that has major significance for developers navigating complex building and zoning rules.

“There’s a bright line between when something is no longer an alteration and then has to be filed as a new building permit, and this is something the Department enforces carefully,” said Mitchell Korbey, a zoning and land use expert at law firm Herrick Feinstein.

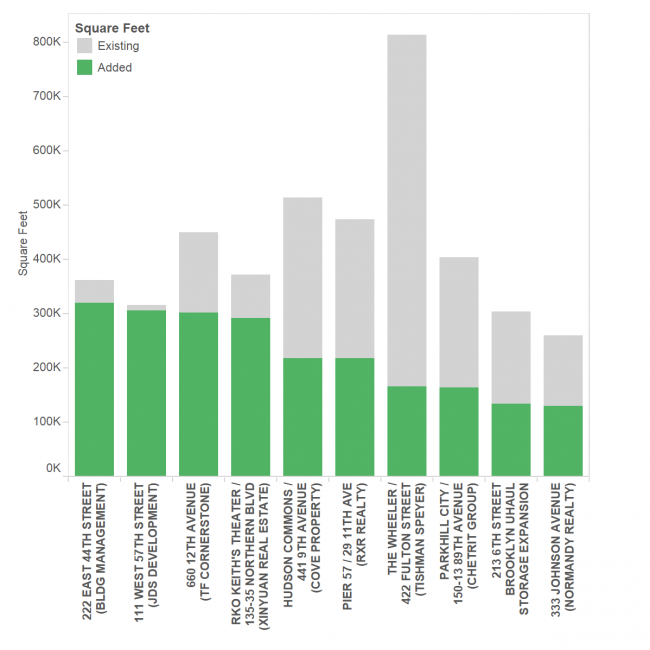

The 30 largest alteration jobs currently in progress — with additions ranging from 62,000 to 320,000 square feet — are expected to add a total of 3.6 million square feet of floor space to the city, according to a data analysis by the The Real Deal. That compares with the approximately 190 million square feet under way in new building filings, the analysis showed.

Here’s a quick primer on what determines whether it’s a new building or an alteration, and why developers opt for one over the other.

Old code, new code

In its simplest form, DOB rules require all jobs that preserve any existing building elements – including parts of foundations or facades – to be filed as “alterations” and not as “new buildings.” Basically, either you totally demolish, or you amend it.

Alterations to old buildings are generally allowed to follow old building codes (with exceptions for things like safety and the environment), which is often advantageous to developers looking to maximize returns on their space. But if an “alteration” more than doubles a building’s floor area (technically, the cutoff point is a 110 percent increase), then the latest building code comes into effect as if it were a brand new building.

But the calculus doesn’t end there. Even if a building becomes subject to new building codes, it might still be grandfathered into old zoning rules. Generally speaking, pre-existing buildings whose form or use violate new zoning rules can be altered as long as they don’t make the non-compliance worse. On the other hand, new buildings almost always have to conform with the latest zoning rules.

If it seems like this distinction between the rules for new and altered buildings might encourage developers to “game the system,” city officials have considered how to combat it.

“Many years ago, there were concerns being raised in a particular corner of Brooklyn where folks were seeking to get permits and maintain a foundation line and yard line, but they were for all intents and purposes tearing down the home,” said Korbey. “They didn’t want to apply for a new building permit because that would have meant that they’d have to comply with new yard requirements.”

The New York City zoning resolution now states that if more than 75 percent of a building’s floor area is demolished or otherwise destroyed before further construction, it will be treated as a new building for zoning purposes. Likewise, the DOB has clarified that its 110 percent increase rule does not include floor space that will be removed during construction (or was added very recently). These clarifications make any rule-bending around the New Building/Alteration distinction much less likely.

Building codes and zoning rules are hardly the only reasons a developer might want to alter an existing building instead of starting from scratch. Landmark preservation and other aesthetic considerations can also encourage “adaptive reuse” of existing structures.

Although adding new structures to an old building can often be more challenging than starting from scratch, due to incompatibilities in structure, materials, and utilities, under the right conditions it may also save time and money. For example, Cove Property Group’s decision to repurpose an existing building for its Hudson Commons project at 441 Ninth Avenue — instead of building from the ground up — will save 16 months of construction time and millions of dollars.

“The existing building that was there had very good bones,” said Amit Patel, a partner at Cove. “With those ceiling heights, you could achieve this industrial sort of feel that’s very different than all the other buildings in Hudson Yards, a unique product that’s very desired by tenants.”

For JDS’ CEO Michael Stern, it ended up being a wash at 111 West 57th Street.

“There’s not necessary any pro or con to whether you meet the definition of a new building or not,” he said. “In the case of 111 West 57th Street, both the tower and the landmark are subject to the more rigorous code. We actually have to widen the staircases in the landmarked building to meet the new building requirements.”

According to filings reviewed by TRD, these are the five largest alterations taking place in New York City, in terms of square feet added:

1) 222 East 44th Street, BLDG Management — increase of 319,774 sq. ft. (770 percent)

This 43-story residential development from Lloyd Goldman’s BLDG is being built on the site of an existing six-story parking garage, whose structure is being kept to house parking for residents as well as various amenities. The new building will also cover the lot of a neighboring 11-story building that was fully demolished. Nevertheless, the preservation of the parking garage means the development had to be filed as an alteration.

2) 111 West 57th Street, JDS Development Group, Property Markets Group — increase of 305,662 sq. ft., 2850 percent

This skinny super-tall tower is being built on the site of the landmarked Steinway Hall, the former flagship building of the Steinway & Sons piano company. JDS and PMG bought Steinway Hall in 2013 and will now include the building as part of the skyscraper’s base, with some of the tower’s residential units being located in Steinway Hall’s interior.

3) 660 12th Avenue, TF Cornerstone — increase of 303,147 sq. ft. (200 percent)

This two-story FedEx distribution center on the Far West Side, owned by TF Cornerstone, is adding five floors of commercial space including offices and a Toyota dealership, benefiting from a 2011 rezoning that allowed for the expansion of car dealerships in the area. The existing FedEx building had previously unused development rights, and was constructed to eventually support additional structures on top of it. In April, Jack Guttman’s Glasshouses inked a 75,000-square-foot deal for an events space at the building.

4) RKO Keith’s Theater, Xinyuan Real Estate — increase of 292,048 sq. ft. (360 percent)

This long-abandoned vaudeville and movie theater in Flushing was bought in 2016 by Chinese firm Xinyuan Real Estate, which filed plans for a 14-story condo complex on the site. While the theater’s exterior will be demolished, the landmarked interior will be rehabilitated and preserved as part of the new building. The former ticket lobby will be converted to retail space and the grand foyer will serve as the entrance to the residential area. While the Landmark Commission expressed some concerns about continued public access to the grand foyer, it ultimately gave the project approval to proceed. In December, TRD reported that the 269-unit project had stalled amid greater troubles within Xinyuan.

5) Hudson Commons, Cove Property Group — increase of 218,904 sq. ft. (74 percent)

Cove Property Group is adding 17 new office floors to an existing eight-story office building near Hudson Yards at 441 Ninth Avenue, offering space for a range of tenants including TAMI (Technology, Advertising, Media and Information), fashion, financial services and legal firms. Harnessing the existing structure while incorporating modern elements such as outdoor terraces and higher windows, this renovation plays into a theme of “adaptive reuse,” which will also allow Cove to save over a year on the construction schedule.