A former banana importer, a fraudster deported from the United States and the co-owner of a major Russian telecommunications company. Sergei Adoniev is all of the above.

And more recently, the Russian oligarch and another wealthy telecommunications magnate, Albert Avdolyan, became investors in Manhattan’s future second-tallest skyscraper, 111 West 57th Street, a supertall condominium project built for the world’s ultra-wealthy.

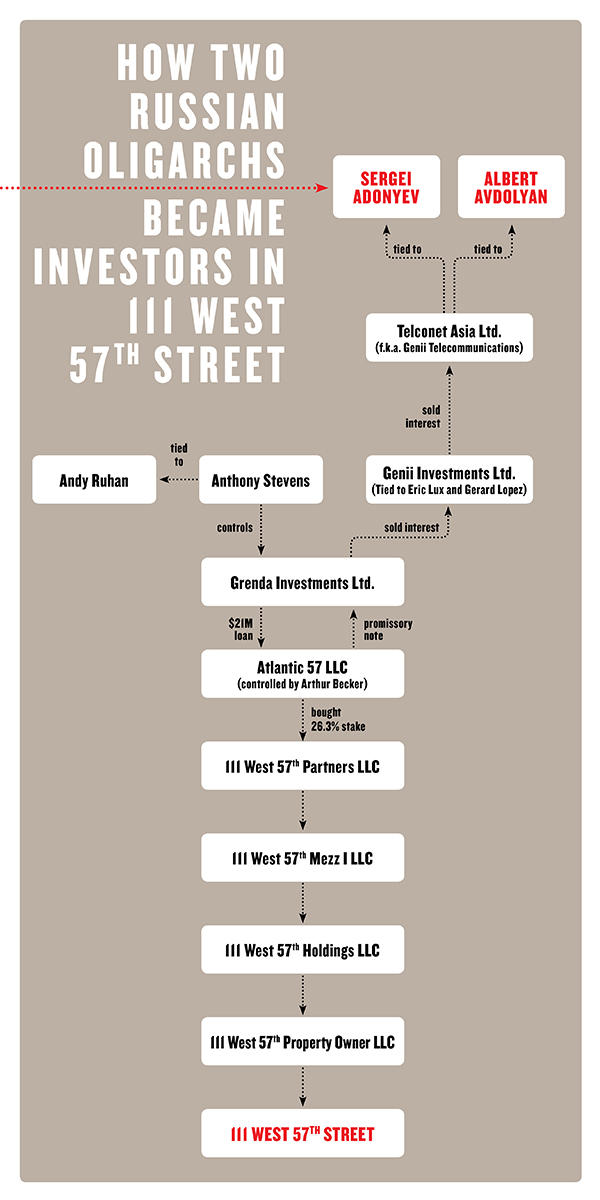

The $21 million investment, disguised behind a series of frontmen, shell companies and promissory notes, was known only to a small number of people. Other investors in the construction project, including AIG, Apollo Global Management, Madison Realty Capital and developers Michael Stern and Kevin Maloney, all declined to comment on the record. Sources involved in the project told The Real Deal that those investors were kept in the dark about the Russians’ role.

That Adoniev and Avdolyan were able to keep their involvement a secret for so long shows how the global rich use offshore companies and elaborate funding structures to funnel millions into Manhattan’s real estate market virtually without a trace. The practice is legal, and lays bare how savvy investors can navigate around government systems that struggle to track the flow of what the International Monetary Fund estimates is more than $12 trillion in offshore corporate wealth.

“Moving money offshore – while a common practice in Russia – might not look good for either that individual or the inner circle of government if that activity were traceable, hence the potential need for secrecy,” said Mark Hays, a campaign adviser to Global Witness, a nonprofit that spotlights offshore money flows.

Although Adoniev does not appear on any sanctions lists, he has close ties to the Russian government and admitted to committing a felony in the United States. His criminal history has drawn scrutiny from investors, and in 2012, when one of Russia’s largest telecommunications companies, Megafon, issued a prospectus to launch an IPO, it pointed to Adoniev’s past as a risk factor, as he was a minority shareholder at the time.

His business partner Avdolyan lacks the same degree of notoriety, but he sports the same classic oligarch flash: last year the telecom magnate hosted a $10 million wedding for his son in Los Angeles, where Lady Gaga staged a performance.

In 2011, when Adoniev and Avdolyan’s company, Telconet Capital, entered a joint venture with Rostec, a Russian state-owned technology conglomerate that is now placed under sanctions by the U.S., Vladimir Putin was pictured overseeing the signing of the partnership. The pair were also present at Putin’s annual gathering of Russian business leaders in 2014 — the same year they invested in 111 West 57th Street.

“A majority of the people I deal with would not be happy about this,” said a New York-based real estate attorney, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “You generally don’t want people like this in your deals.”

Representatives for Adoniev and Avdolyan declined to comment for this story.

How they did it

Sergei Adoniev and Albert Avdolyan (Credit: Wikipedia and Alchetron)

To move their money into New York real estate, the pair of oligarchs relied on clever accounting methods.

An entity that Adoniev and Avdolyan controlled extended loans to a series of frontmen and shell companies — including an Irish racing car driver, a Luxembourg investment firm and offshore companies — that ended with New York-based real estate investor Arthur Becker, who bought a stake in the project.

The interest on these loans was structured in a way that made it equal to the profit an equity investor in the project would make, according to court records. In other words: Adoniev and Avdolyan made a de-facto equity investment disguised as a loan.

The practice offers tax benefits in some countries, and has been used by private equity companies like the Blackstone Group. For investors like Adoniev and Avdolyan, it also offers another crucial advantage: plausible deniability. Because they didn’t technically buy a stake in the project, the oligarchs and their associates can claim that they aren’t part-owners.

“There’s nothing illegal about that, you can set up your affairs in awkward ways if you choose to,” said Adam Smith, a partner at Gibson Dunn and former adviser to the Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control. “The finance sector is endlessly creative in finding ways to do things good, bad or otherwise.”

A source close to the project, speaking on condition of anonymity, dismissed the loans as the equivalent of a bank issuing a mortgage and then passing part of it on to other investors — a common practice in commercial real estate.

“You borrow money and the bank goes out and syndicates it, provided they’re still a majority owner of the loan note. And that’s where the relationship continues,” the person said. “You sort of become indifferent to who they sell it to, unless it’s a criminal. In which case you start to say, ‘What the fuck is that about.'”

The Russians’ involvement only adds to the uncertainty around 111 West 57th Street. At 1,438 feet, the luxury condominium tower is set to become the city’s second tallest building by roof height once completed, eclipsed only by competitor Extell Development’s nearby Central Park Tower. With a projected sellout of $1.37 billion and some apartments expected to ask more than $50 million, 111 West 57th Street is one of the most ambitious construction projects in the city.

But the development has been plagued by delays, cost overruns and infighting among its investors. Last year, a junior lender foreclosed on the tower after its owners, locked in a legal fight, failed to agree on a refinancing.

But the development has been plagued by delays, cost overruns and infighting among its investors. Last year, a junior lender foreclosed on the tower after its owners, locked in a legal fight, failed to agree on a refinancing.

Whether Adoniev and Avdolyan will ever make any money off the project is unclear — the foreclosure eliminated their interest in the building. Sources told The Real Deal that their investor group, through Becker, is still negotiating with the developers over whether it will get a stake following the foreclosure.

Spruce Capital Partners, which foreclosed on the project last year, denied the claims. “Spruce Capital Partners have never had any negotiations with Becker’s group,” the firm said in an emailed statement.

Bananas and fast cars

Russian media reports and bloggers have in recent years documented the rise of Adoniev to his rank among Russia’s wealthiest men. As the co-owner of Yota, one of the country’s largest makers of mobile phones, the 57-year-old leads a flashy life, and is recognizable by his flowing mane and variety of thick-rimmed glasses. This year, he was reportedly dating a famous Russian actor and director, Olga Dihovichnaya, and Forbes Russia pegged his net worth at $700 million.

“He’s like other Russian businessmen: started selling computers, and was also one of the major suppliers of bananas to Russia,” said Timothy Dziadko, a Russian journalist who profiled Adoniev for Forbes. “Before Yota, he was almost unknown in Russia.”

After working as a computer salesman and banana importer in St. Petersburg during the early 1990s, he and another associate, Oleg Popov, were reportedly pursued for links to a cocaine haul seized at Finnish-Russian border, and moved to the United States.

In 1996, a Los Angeles court sentenced Adoniev to 30 months in prison for his role in a scheme that included bribing a Kazakh official to secure a contract to deliver 25,000 tons of Cuban sugar to Kazakhstan, according to court records. After most of a $6.7 million agreement was paid in advance, the sugar never arrived. (Popov, who was involved in the scheme, was allegedly shot dead in St. Petersburg before the case started. However, an American life insurance company found inconclusive evidence that his death even happened.)

Adoniev was deported back to Russia and he kept a low profile, until 2007, when he and Avdolyan emerged as the majority owners of Scartel, the parent company of Yota.

As the business boomed, so did their taste for the arts, philanthropy and fast cars. Avdolyan reportedly bought homes in Beverly Hills and Adoniev embarked on a film project. In January 2014, Yota Phone announced a partnership with the Lotus Formula 1 racing team, where they partnered with Andy Ruhan, an Irish businessman and racing car driver known for one of Britain’s most expensive divorce cases, and Luxembourg investors Eric Lux and Gerard Lopez.

Soon, the Russians and their new partners joined forces to fund 111 West 57th Street.

Revealing the money web

Michael Stern, Kevin Maloney and Arthur Becker

In early 2013, New York developers Michael Stern and Kevin Maloney signed a contract to buy the land under the Steinway Building in Midtown Manhattan. But they didn’t have the money to build the supertall condo tower they had envisioned, so over the following months they lined up equity investors to pay for the construction costs.

“You never go into partnerships under any circumstances where you have a bad feeling,” Maloney told TRD last year when asked about the choice of partners. “It’s like getting married. When you see people walking down the aisle together, do you think they’re thinking, ‘Wow, I can’t wait to get out of this?’”

AmBase Corporation, an obscure holding company based in Greenwich, Connecticut, paid $56 million for a 59 percent stake in the project. And Atlantic 57 LLC, an entity controlled by Arthur Becker, a real estate investor and the former husband to fashion designer Vera Wang, bought a 26.3 percent stake in the property’s operating partnership.

Here’s where it gets complicated: Becker paid for his investment with a $21 million loan from an entity controlled by Anthony Stevens, an associate of Ruhan’s. But this was no ordinary loan. Instead of simple interest payments, the entity, Grenda Investments Ltd., was promised an annual return of 20 percent on its investment, plus 75 percent of any further profits made by Becker’s entity, according to a lawsuit filed against Grenda in New York. In other words: Becker agreed to pass the bulk of his equity profit on to Ruhan’s group. So this was a loan, in theory, but it promised the returns of an equity investment.

As it turns out, Ruhan was also merely a middle man. In May 2014, Grenda, registered in the British Virgin Islands, signed a deal with Genii Investments Limited, controlled by Lux and Lopez. Genii bought part of Ruhan’s stake, and in return it was promised 49.9 percent of his profits from the project, according to court records.

Here’s where Adoniev and Avdolyan come into play. As Genii signed its deal with Ruhan’s entity, it simultaneously signed a separate agreement passing on its interest in 111 West 57th Street to another entity, Hong Kong-based Genii Telecommunications Limited. The Russian telecommunications mogul’s fingerprints are all over that company, public records show.

In January 2016, Genii Telecommunications changed its name to Telconet Asia Limited, aptly named after Adoniev and Avdolyan’s investment company, Telconet Capital, according to Hong Kong company records. Court records show that a certain “Ms. Lapshina” represented Telconet Asia in some communications with Ruhan’s entity. Ekaterina Lapshina is a close associate of Adoniev’s and managed his investments. When reached by phone, Lapshina declined to comment.

So, to recap: Arthur Becker bought a 26.3 percent stake in 111 West 57th Street, agreed to pass most of his profits on to an entity controlled by Ruhan, who in return promised 49.9 percent of his profits to a company tied to Adoniev and Avdolyan. All of this was done through a series of loan agreements and promissory notes.

Gerard Lopez, Andy Ruhan and Eric Lux

A year later, the developers landed $725 million in loans from AIG and Apollo, and the skyscraper began to rise. If all went according to plan, the Russians would merely have to lean back and wait for their payday, but it didn’t work out that way.

As construction delays and cost overruns mounted, the developers, Stern and Maloney, fell out with their Connecticut-based investor AmBase, who sued them. As the legal battle waged on, the project’s $325 million mezzanine loan fell out of balance, and in mid-2017 the project’s most junior lender, Spruce, foreclosed on the tower.

With one sweep, AmBase, Ruhan, Adoniev, Avdolyan, Stern and Maloney lost their interests in the building, although the latter two bought back into the project and continued as its developers, according to sources. Litigation between AmBase and the developers continues to this day.

Ruhan’s group and the Russians also had a falling out. In October 2017, Telconet Asia filed a lawsuit against Ruhan’s Grenda in New York State court, alleging that it pocketed payments from the tower that it should have passed on to Telconet. That lawsuit formed the basis of much of TRD‘s reporting in connecting the oligarchs to the condo project. Ruhan’s entity denies the allegations, and litigation continues.

With the future of his investment in 111 West 57th Street unclear, Adoniev has something else in store for Manhattan. Through a British trust, records show the Russian donated $2 million to Hudson Yards’ new culture center, “The Shed,” which will be used for a performance set to take place sometime in 2019.