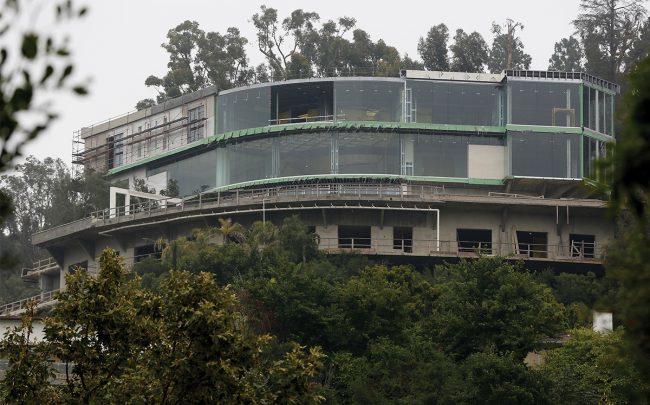

In November, a judge ordered Mohamed Hadid to destroy a 30,000-square-foot Bel Air mansion that the developer has kind of built.

The extraordinary order from Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Craig Karlan echoed and amplified arguments by the neighbors who filed a lawsuit against Hadid over the mansion.

Joe and Beatriz Horacek and Judith and John Bedrosian alleged that the hyperbolic modernist kingdom at 901 Strada Vecchia Road violated city building codes and was a public danger.

(Critics pan the mansion as the “Starship Enterprise.” If anything, it looks like a chic grain silo.)

In taking on Hadid, the plaintiffs were targeting not just a real estate developer but a distinctive variant of celebrity who has been made famous from his cycles of ruin and redemption, reality television and being the father of supermodels Gigi and Bella Hadid.

They were also taking on something of a reviled visionary. Hadid has made his millions by building bombastic mansions that neighbor genteel estates, a strategy that has made him the target of dozens of lawsuits.

Judge Karlan, though, wasn’t worried about Hadid’s nouveau riche tastes making the denizens of Bel Air clutch their collective pearls. He was concerned about a building falling down a hill.

“It’s not even a close call in my mind that the plaintiffs are at a legitimate risk of suffering damages and harm to their homes,” Karlan said, according to court records. “[The structure] just cannot be left in place. It cannot remain, knowing what we know now.”

Karlan’s decision came after Russell Linch, the former project manager for 901 Strada Vecchia, alleged that multiple Los Angeles Department of Building employees had either illegal or inappropriate interactions with Hadid, ranging from accepting gifts to setting up an office at a Hadid nursery.

“The things that he says in here are really disconcerting, in terms of what went on with the city and the inspections,” Karlan said of Linch’s declaration.

In a recent phone interview, Linch said the FBI has interviewed him several times now regarding the relationship between Hadid and city inspectors.

Linch finds Hadid corrupt and corrupting, which leads to the obvious question of why he worked with the man for many years.

Linch’s answer is, perhaps, an unintentional compliment.

“I wanted to work with him,” he said, “because I wanted to be part of history.”

The megamansion pioneer

Hadid, 71, came to Los Angeles from Washington, D.C. in 1991, leaving behind a foreclosed home, a shuttered hotel, a substantial office development business and a failed marriage.

Back then, Hadid was warring with another big developer in transition, Donald Trump, over plans to construct a hotel in Aspen, Colorado.

Like Trump, Hadid’s real estate empire soared in the ’80s, only to crash amid the recession and savings-and-loan debacle of the early ’90s.

“In the ’80s, everybody was a genius,” Hadid said in a soft-spoken voice with a pronounced Arab accent. “Then everything crumbles on you.”

Hadid is saying this a week after Karlan’s demolition order, over lunch at a generically fancy restaurant in a Beverly Hills hotel. He enjoys a gentle physical attractiveness, armed with a mischievous, boyish smile and glimmering green eyes.

These qualities lightened a conversation that kept circling back to Hadid accusing Joe Horacek of extorting him. But when not discussing the Strada Vecchia controversy, Hadid is a bit more measured.

From left, Bella, Yolanda and Gigi Hadid pose with Mohamed Hadid in 2016.

“I got married, and I kind of started a new life here,” he said, referencing his 1994 marriage to Dutch model Yolanda van den Herik. He started a second family (he was married with two children in Washington), began seriously painting and changed his development focus.

Just as he forecast the D.C./Northern Virginia commercial real estate buildup that persists today, Hadid saw L.A. as a prime spot to build mansions so big that they become like private islands with their own brand names.

“I didn’t understand the market,” he said of L.A. “There was too much office space Downtown. And I just found a niche in the market, that people are looking for a lifestyle, rather than just a home. So I start building lifestyles rather than just homes.”

Hadid bought distressed properties in the toniest parts of L.A. County — starting with a 1993 purchase on Nimes Road in Bel Air for $3.5 million — and built megamansions on the land.

His bets began to pay off. He sold a grandiose abode he developed on North Carolwood Drive in Beverly Hills, which looks like a riff on the “Gone with the Wind” estate, for $18.5 million. It was later the site of Michael Jackson’s fatal overdose.

Hadid subsequently sold the “Crescent Palace” in Bel Air for $33 million, and the “Palazzo di Amore” in Beverly Hills for $35 million.

The Nimes Road property, though, proved to be the pièce de résistance: a 48,000-square-foot nod to a French chateau with swan pond and ballroom that Hadid branded Le Belvedere. The $50 million purchase price marked the highest recorded U.S. residential sale of 2010. (Hadid actually stayed there after he sold it, negotiating a sale-leaseback agreement.)

“Mohamed obtained a piece of dirt at Nimes and created something special,” said James Zelloe, a Washington, D.C., attorney who has represented Hadid since the mid-1980s. “In his properties, he incorporates everything that he sees and experiences throughout the world. It’s almost if the true American melting pot is achieved in his construction.”

Or, as Hadid put it, “I was the guy who started building these ultra, ultra, ultra-big houses.”

These ultra-big houses are a perhaps underappreciated turn in L.A. real estate that drove other colorful developers like Nile Niami and Bruce Makowsky to basically print money.

Take the Bel Air spec mansion Makowsky sold for $94 million in October. Makowsky was mocked for his ostentatious creation, dubbed “the Billionaire,” because of its over-the-top amenities like a candy room and because of its several markdowns from an original asking price of $250 million. But Makowsky almost assuredly made a fat profit from the sale of a site he bought for $7.9 million. If the Hadids and Makowskys of the world were in, say, tech instead of modern mansion development, their profit margins would be revered, not mocked.

Still, millions of dollars need to be put into each development, and how Hadid found money for his projects had not been clear.

Unlike Trump, Hadid does not come from money. He was born in Nazareth in 1948, became a refugee at the age of 1 during the Arab-Israeli War and moved first to Syria, then Lebanon and then Tunisia, where he spent much of his childhood. In 1964, he moved to Northern Virginia after his father got a job at Voice of America.

Hadid never graduated college, though he did spend a season as a placekicker at Winston-Salem State in North Carolina and later took math and engineering classes at Shaw University, a historically black institution in Raleigh.

For decades, reporters have asked Hadid where he gets his money. And for decades, he has given the same response, verbatim, that he did to D.C.-based business magazine Regardie’s in 1988 — “I get money the same way everybody else does, from banks.”

Hadid’s Strada Vecchia project (Credit: AP)

One such institution is First Credit Bank, which Iranian-born businessman Farhad Ghassemieh opened in 1983 in West Hollywood. Ghassemieh, who still serves as bank president and chair, said Hadid comes to him “pretty much whenever he is building a large house.”

Megamansion loans are “labor-intensive,” Ghassemieh said, because “it requires going to the site each month and making sure the lendee is spending money as they say they are.”

But Hadid makes good on his loans. “Until recently,” Ghassemieh said, “our relationship has been very good.”

The ‘Starship Enterprise’

Hadid saw Strada Vecchia as “just a beautiful home” with curved glass and a view of Santa Monica, surrounded by almost 400 newly planted trees. He paid $2 million for the site in 2011, purchasing it through shell company 901 Strada LLC.

Hadid brought in his usual team including Linch, who has drafted design plans for Hadid for over a decade. After building the first fifth of the mansion with his own money, Hadid approached First Credit for a $17 million loan.

For Hadid, Strada Vecchia would build upon the success of Le Belvedere and ramp up his burgeoning celebrity profile. The developer had opened the Hadid Art Gallery in West Hollywood, and in 2012 he snagged a recurring role on Bravo’s “Real Housewives of Beverly Hills,” a launching pad for Gigi and Bella’s careers.

In the midst of his brush with fame, Hadid altered Strada Vecchia from plans the city approved. This included building an IMAX movie theater, and seemingly exceeding a 36-foot height limit by building 70 feet above ground.

(Hadid contends Strada Vecchia is not a 70-foot-tall building, but two 35-foot tall structures. “It’s actually two buildings, but the neighbors look at it from the bottom to the top as one building.”)

The revamped project not only (arguably) zoomed past the prescribed height, it brought up structural concerns. City inspectors said the foundation was not drilled deep enough into the ground, and horizontal support beams were not evenly spread out.

In 2014, the Building Department issued a stop-work order, which Hadid ignored, resulting in the L.A. city attorney bringing criminal charges against him for building without a permit. Three years later, Hadid pled no contest, receiving three years of probation and 200 hours of community service. He characterizes the plea as a selfless act.

“When I went in and pled no contest, it’s because I just didn’t want anybody to get hurt,” he said. “It’s all small guys I work with.”

But another threat to the project, Karlan’s demolition order, didn’t arise from city inspectors and prosecutors. It came from Joe Horacek.

Horacek and his wife are the closest neighbors of 901 Strada Vecchia. Joe Horacek has lived in Bel Air for 70 years, working as a lawyer in L.A. for a half century. He is a founding partner of law firm Manatt, Phelps & Phillips. Town & Country called him “probably the WASPiest Hollywood entertainment lawyer alive.”

Mohamed Hadid (Photography by Kevin Scanlon)

In Hadid’s telling, Horacek is also the NIMBYest neighbor alive.

“He called the city on me every day. ‘Somebody is working there. Somebody is doing this.’ City inspectors were on the site every day,” Hadid said.

Hadid also claims that Horacek tastelessly threw Gigi and Bella into the feud, feeding tabloids dry stories about civil court proceedings and hoping they would run a piece as an excuse to post a picture of Hadid’s glamorous daughters.

Hadid’s strongest accusation is that Horacek extorted him, asking for $3.5 million in exchange for peace.

The extortion claim is in a countersuit Hadid has filed against Horacek. Karlan has not made any rulings on the countersuit, but Hadid already seems defeated.

“I am hoping the judge can be fair,” he said. “But I’ve been attacked in the public eye so much that I feel like I’ve been tried already.”

Horacek denied the extortion claim and denied using Gigi and Bella to publicize the feud.

“The ‘Starship Enterprise’ has become widely known as the most illegal house in the United States,” Horacek said in an email. “It’s not a surprise the media has taken notice.”

Horacek turned down multiple interview requests, preferring instead to cite the court record, which certainly leans in his favor: In November, three weeks before Karlan’s civil court order, the city attorney reopened its criminal case against Hadid to push for demolition. And shortly after Karlan’s order, a federal judge dismissed 901 Strada LLC’s November bankruptcy filing.

“This is an attempt to use me to undo what the state has done,” Judge Sheri Bluebond said in court in December. “I don’t think that’s appropriate.”

“They take this, they take that”

“For years, it was a mystery how such a huge structure could have been erected given that city building inspectors were frequently on site,” Horacek’s lawyers, Ariel Neuman and Shoshana Bannett of Bird Marella, wrote in a motion filed in December. “But discovery in the civil case solved that mystery. As Hadid’s own contractor on the project, Linch, attested, Hadid bribed at least one building inspector who was tasked with working on the project.”

Hadid’s narrative of the rise and fall of Strada Vecchia is that well-connected neighbors ganged up with City Hall to conspire against him. But the record from civil court proceedings — namely, the declaration from Russell Linch — offers evidence that, in fact, it was Hadid who was in bed with City Hall.

Linch has worked with Hadid on numerous sites as project manager, including Crescent Palace, often supervising teams of over 100 workers. In an interview, Linch said he stopped working with Hadid at the end of 2018 because Hadid demanded Linch doctor blueprints so Strada Vecchia could get its building permit back.

“He kept bugging me to do it and got really hostile,” Linch said. “That was the straw that broke the camel’s back.”

Hadid said Linch is flat-out lying. He pointed to a deposition from November 2018 — before Linch stopped working for Hadid — in which Linch makes no mention of the charges he later leveled in the declaration.

Hadid contented that Linch’s personal life was unraveling, that he felt vulnerable and got taken advantage of by Horacek. “Linch has been cahooting with Horacek,” Hadid said.

But Linch’s testimony seems, as Karlan put it, “really disconcerting.”

The declaration’s most explosive assertion is that Hadid spent $20,000 to install luxury kitchen cabinets at the home of Anthony Anderson, the Building Department’s senior inspector on Strada Vecchia.

Anderson also allegedly instructed Linch to hire his son, Anthony Jr., “because his son was having problems making ends meet.”

The St. Regis Aspen

The Building Department responded to this part of the declaration by stating that it turned over to the FBI possible evidence that an inspector has received “items of value” at Strada Vecchia. Anderson has since left the department, and attempts to reach him and other inspectors Linch said were close to Hadid were unsuccessful.

One was Jeff Napier, who “was very friendly” with Hadid, frequently posing for pictures with him at 901 Strada Vecchia and having lunch with the developer each week. Another was Bryan Kehoe, who grew so close to Hadid that Kehoe helped build the very project that he inspected.

Kehoe and another inspector, Todd Maland, “frequently hung out at a nursery, owned by Hadid, located near the Van Nuys airport,” Linch declared, adding, “Kehoe also served as an inspector at 901 Strada Vecchia and approved the pool demolition work that Kehoe himself had performed.”

Hadid acknowledged that Kehoe worked from his Van Nuys property, and even assisted on the Strada Vecchia pool. But he claimed that Kehoe had retired from the Building Department by the time the two worked together.

Hadid maintains no one from the FBI has interviewed him, and he denies any foul play.

“I have never bribed anybody, never given a dime to anybody,” he said. “Do you think I would go to an inspector walking around and say, ‘Do you want some cabinets?’ It’s so outrageous.”

But moments later, Hadid acknowledged that “in our industry, people steal a lot of things.”

“They take tools, they take this, they take that,” he added. “I can’t control what’s stolen and what’s given out.”

Kim Arther, chief inspector with the Building Department, referred questions to the city attorney’s office. “The matters are in court, and are being handled by the city attorney, so LADBS has no comment at this time,” Arther emailed. The city attorney’s office declined to comment. Alex Comisar, a spokesperson for Mayor Eric Garcetti, did not respond to questions sent, except to say: “The mayor expects everyone to cooperate fully in any federal investigation.”

FBI investigations are not new to the Building Department, which was ensnared in probes in the early 2010s. Those investigations led to city inspector Samuel In pleading guilty to federal charges that he received $30,000 in bribes from developers.

The Palazzo di Amore

“The L.A. Building Department has a history of corruption and lax management,” said Kathay Feng, executive director at Southern California Common Cause.

A big part of the problem, Feng said, is that inspectors are “a dispersed workforce,” fanned out over a notoriously sprawling city.

“These are the sole people who are going out onto a site to determine whether or not changes are being made,” she said. “It creates a culture where it is acceptable for individual inspectors to either be overbearing in demanding changes, or to accept violations in exchange for payments.”

A colorful guy

Hadid was never supposed to have a legal fight livelier than the one 30 years ago with Donald Trump, a prize match to see which East Coast developer would get to build a really expensive Aspen hotel.

Trump took his desire for a Trump Hotel public, crudely arguing to locals that he would be a better community fit than Hadid.

“Donald started coming into town and he had cartoons of me on a camel, with a harem behind me,” Hadid said.

In 1987, Hadid spent $43 million on land that included a parcel set aside for the hotel. He spent days in court arguing why he could build a five-star Ritz-Carlton hotel, and nights throwing parties and driving his Bentley convertible.

“I was a very colorful guy in Aspen, Colorado,” Hadid recalled.

Hadid effectively won the suit. He built the hotel and even got to play the role of benevolent developer, constructing an ice-skating rink for the city.

In between Aspen and Strada Vecchia, though, Hadid has faced other legal problems. A review of court records shows that Hadid has, conservatively speaking, been sued about 60 times in California courts since he relocated to L.A.

Many were breach of contract claims. Sylvester Stallone, for instance, sued Hadid for $1.4 million in 2012 for design work the movie star said was so poor it was tantamount to fraud. Hadid countersued, saying Stallone threatened to “smash my head with a baseball bat.” The parties settled in 2013.

Ex-Hadid employees, meanwhile, have alleged that he fraudulently filled out Internal Revenue Service forms in order to avoid payroll taxes. One former employee, Mexican citizen Juan Carlos Gonzalez, filed a RICO Act lawsuit on the matter in 2014. It was settled confidentially last April.

Then there’s Hadid’s personal bankruptcy, which he filed for in 1999 in California’s Central District. The case closed in 2004, but it kept reopening as creditors claimed Hadid never paid what he owed.

In 2011, Houston-based insurer Stewart Title Guaranty Company opened an adversarial proceeding against Hadid, stating he had gone 10 years not paying any of $1.75 million he owed. The bankruptcy court ruled in favor of Stewart Title, finding Hadid now owed the creditor $3.4 million.

Then, in 2012, Stewart Title reopened the bankruptcy again, saying Hadid still hadn’t paid. The company voiced frustration not just with Hadid’s failure to pay, but with how it could ever collect from the labyrinth of LLCs in which the developer stored his money.

“Hadid’s continued failure and refusal to satisfy the judgment and his penchant for holding all of his viable assets in the name of various limited liability companies leaves Stewart Title with no option other than to charge Hadid’s membership interests,” the company’s filing read. The case was confidentially settled a year later.

One case that did not quietly settle was a lawsuit by hikers of a Coldwater Canyon Drive trail where Hadid planned a project. A trial court ruled with the hikers that Hadid planned to illegally develop in an area set aside for the public, but an appellate court ruled for Hadid in 2016, finding that the trail no longer qualified as a public easement.

There is no love lost from the hikers. “My memory of Hadid is that he testified in the trial court about how great he was,” said Stephen Jones, the hikers’ attorney. “It was as if in his country, if you were a famous or powerful person the trial court would not rule against you. I was horrified to see him win in the court of appeal. Was Hadid right all along?”

The way forward

Sitting in the Beverly Hills restaurant, delicately sipping his tea, Hadid admits he’s kind of stuck.

A federal judge may have declared Strada LLC’s bankruptcy filing a ruse, but Hadid really does owe creditors about $28 million, including the $17 million to First Credit Bank.

All told, Hadid says, he has spent about $50 million on Strada Vecchia, which makes him particularly upset about paying another $5 million toward tearing it down. In a court motion, Hadid argued that the LLC doesn’t have the $500,000 customary fee for a receiver, much less money for demolition costs.

“Somebody has to take the blame for it,” he said of the property. “I don’t expect that the city should, or the taxpayers should, but I’ve been paying taxes on that property of almost $300,000 a year.”

Hadid can appeal Karlan’s demolition order, and says that he will, but his lawyers had not filed an appeal as of press time. The judge, meanwhile, has begun with the logistics of demolition, including appointing a property receiver, Douglas Wilson (Karlan credited Wilson in court as the man who repaired the three missing holes at Trump National Golf Club in Los Angeles.)

Hadid says he can still make a city-code-compliant Strada Vecchia home, but the developer sounds unconvincing even to himself.

“I don’t want to talk about the city, because it’s a very complicated thing,” he said. “I think they’re just, in my opinion, they’re just fed up with this project, as I am fed up with this project.”

But he also seems to be taking stock. Though he’s said he is not a political person, Hadid has opened up more in our recent conversations about his immigrant experience, and being an Arab and Muslim capitalist in America. And the developer is eternally proud of his five children, including world-famous models Gigi and Bella.

“All you have to do is look at your legacy,” he said. “And my legacy is these kids.”

There are other projects in the queue, including one in Egypt that Hadid claims will be “the largest residential project in the world — almost 16,000 apartments in one building.”

Strada Vecchia will be “a major setback,” said Hadid’s lawyer, Zelloe. “But I don’t believe that Mr. Hadid is going to roll up and go away.”