This story was originally published in March 2020.

Last November, a 40-year fight over an affordable housing development in Long Island — a legal battle that had gone all the way to the Supreme Court — finally came to a vote.

Despite locals arguing for decades that it would cause traffic and crowd schools, Suffolk County legislators allocated $2.4 million to the 146-unit project in East Northport, a hamlet in the town of Huntington.

For many proponents, the issue boiled down to a largely white community trying to shut minorities out. Indeed, the Supreme Court in 1988 let stand a court ruling that Huntington had violated the Fair Housing Act with racially discriminatory zoning — essentially restricting multifamily development to the town’s urban renewal area, where more than half of residents were minorities. In the white parts of town, expensive single-family homes prevailed.

“We will no longer perpetuate the segregation of our communities,” said Suffolk County Executive Steven Bellone after November’s vote. “Everyone deserves access to fair housing in every corner of Suffolk.”

The same polarized debate is playing out in a host of suburbs surrounding New York City, including Westchester, northern New Jersey and Connecticut, as the shortage of affordable housing grows increasingly urgent.

Many developers say community opposition, byzantine local zoning laws and the economics of affordable housing have prevented them from building more in the suburbs. But Elaine Gross, who runs regional civil rights group ERASE Racism, said the problem is not bureaucracy so much as an undercurrent of racism — particularly on Long Island, where her organization is based.

“They say that this is going to raise our taxes, make our schools crowded,” Gross said. “But if this is a community that is mostly white, they’re really saying, ‘Well, we really don’t want black or brown people.’”

In 2015, the Obama administration introduced the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) rule, requiring local governments to take steps to address segregation in their housing systems. But the Trump administration has worked to unravel the policy.

In 2015, the Obama administration introduced the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) rule, requiring local governments to take steps to address segregation in their housing systems. But the Trump administration has worked to unravel the policy.

The rollback has been a major blow for advocates who say stripping away oversight and accountability will only empower NIMBYism in areas where affordable dwellings are sorely needed and development can be a fraught process.

“Outside of the five boroughs, everyone is fending for themselves,” said George Zayas, principal of Alma Realty, a New York-based landlord and developer with projects in Peekskill, Hempstead, Yonkers and Westchester. Each municipality is its own “little fiefdom,” he added, with layers of unique rules and approval processes.

Community opposition — often coded discrimination — also comes into play. “Affordable housing is taboo,” Zayas said. “There’s this idea of ‘Not here. We don’t want that.’”

A developer who worked in the suburbs said he had also witnessed it. “I definitely think that in some communities there’s a racial dimension to it,” he said, speaking on condition of anonymity. “There’s also a class dimension.”

ERASE Racism’s Gross noted that just one week before the Huntington vote, Newsday had published a startling account of Long Island brokerages steering minority home shoppers away from white neighborhoods. The exposé, which triggered outrage and put the real estate industry on notice, undoubtedly put pressure on local legislators too.

State lawmakers are now subpoenaing brokers to testify after 67 of 68 industry representatives failed to show up to a December hearing.

“There’s a lot of talk about realtors right now because of Newsday’s investigation and that’s a good thing,” she said. “But it’s not just about the realtors — it’s about the municipalities, local governments and what they’re doing and not doing.”

The federal Fair Housing Act more than a half century ago made it illegal to refuse to sell or rent a home to anyone because of race, disability, religion, sex, family status or national origin.

Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson, in an interview with The Real Deal late last year, defended his shift away from the Obama-era measures. “I expect criticisms,” he said. “People are creatures of habit. They don’t like change.”

What that change will look like, though, is hard to determine — the policy is still new. But Moses Gates, vice president for housing and neighborhood planning at the Regional Plan Association, said he believes slashing the Obama fair-housing rule will allow local governments to claim they are doing a good job on affordable housing without being held accountable by Washington.

The Beacon at Garvies Point in Glen Cove, New York

“Where municipalities don’t want [affordable housing] at all, the HUD rule changes kind of reinforced that mentality and makes them a little more secure in it,” he said.

Westchester’s 11th hour

In Westchester County, the threat of drawn-out timelines works against affordable housing projects, said Compass broker Francie Malina, who leads a seven-person team specializing in new development.

“It’s unaffordable to build affordable because, by the time you get approved, you’ve got to charge such a high rent or price for your condo in order to make the money back,” she said.

In recent years, Malina said she has noticed a shift in the shoppers coming to her for homes in Westchester County. “It used to be Manhattanites,” she said. “Now it’s Manhattan, Brooklyn and Queens.”

Most prospective buyers and renters are drawn to the area because they want more space, Malina said, or to send their kids to the public schools.

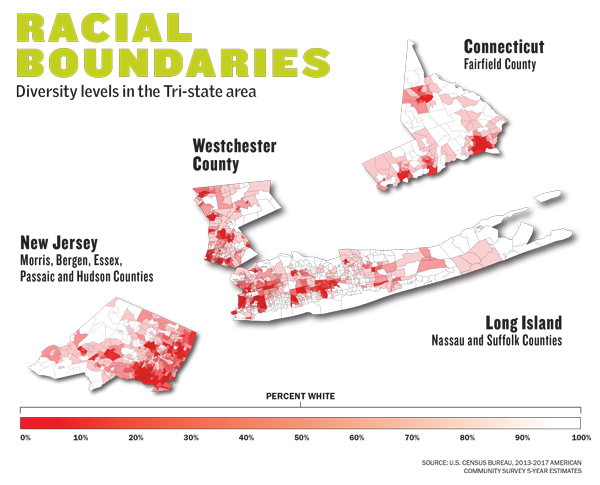

But diversity in Westchester remains minimal. Just 16.6 percent of residents in the county are African-American and 6.4 percent are of Asian descent, according to recent census estimates. Often minorities are concentrated in certain neighborhoods, leaving others with precious few persons of color.

The county has also faced scrutiny over the years for its poor record on fair housing. In 2006, the Anti-Discrimination Center filed a lawsuit against the county arguing that to obtain $52 million in federal funds, Westchester had fraudulently certified paperwork to show it complied with fair-housing laws. As part of a 2009 settlement, Westchester agreed to build 750 affordable units in 30 mostly white communities.

In the years that followed, the county submitted 10 zoning analyses to the Obama administration to prove it had solved its exclusionary housing problem. Every single one was rejected.

Then, in 2017, the fight appeared to abruptly end: Just one day after the county’s 11th attempt, the Trump administration gave it the green light.

A spokesman for the Democratic Caucus of the Westchester County Board of Legislators told The New York Times that the only difference between the 10 rejected analyses and the one that got through was “the administration who approved it.” A HUD spokesman dismissed the idea of governmental bias as “horse hockey.”

Decades before, communities had been designed and constructed without any federal intervention — laying the foundation for modern housing segregation.

Perhaps most infamously, in 1947, Long Island developer William Levitt embarked on a project that would cement his vision of the New York City suburb and become a model the rest of the nation would emulate: white, middle to upper class and conservative.

At the height of the mass-manufacture of Levittown, which sits on a seven-square-mile tract in Nassau County near the village of Hempstead, a house was completed every 16 minutes. The 17,000-home development was a haven for returning World War II veterans, who were incentivized to buy property with inexpensive mortgages and no down payment.

But deed covenants restricted sales to white buyers only. At its launch, Levittown was 100 percent white.

In 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Fair Housing Act into law, but segregated housing remains widespread across the country. In few places is it more pronounced than in Nassau County.

“People have known on Long Island for decades that we weren’t doing the right thing,” Gross said, noting that too much emphasis has been placed on single-family homes, which are no longer inexpensive options.

Six miles west of Levittown sits the multicultural, working-class town of Hempstead. The median income is $58,476, and its population is 51 percent black and 32 percent Hispanic. But in Levittown itself, change has been slow.

The town was 89 percent white with a median household income of $150,900, according to the 2015 American Community Survey. Some blocks remained 98 percent white.

Labyrinthine localities

While development in New York City is governed by the City Council, in the greater New York metro region, some 782 municipalities control their own land use, according to the Regional Plan Association. Long Island alone has 175 zoning and planning districts, including 126 in Nassau County. Westchester has 89 zoning and planning districts, and 396 localities in New Jersey and 76 in Connecticut control their own land use.

Getting zoning variances in the five boroughs can be complicated, but many housing projects don’t require them. In the suburbs, however, nearly every development must get the blessing of local zoning officials, sometimes in the face of fierce opposition from residents.

Getting zoning variances in the five boroughs can be complicated, but many housing projects don’t require them. In the suburbs, however, nearly every development must get the blessing of local zoning officials, sometimes in the face of fierce opposition from residents.

“It all depends on the town and what you’re building,” Zayas said. “If someone really wants affordable housing, they’ll get it done but not if it’s a homeless shelter or 100 percent affordable. If it’s 20 percent set aside for lower-income families, you’ll get comments on the design, but no one has a pitchfork.”

An investigation last year by the Connecticut Mirror and ProPublica showed that dozens of towns in Connecticut had blocked the construction of any privately developed apartments in their communities for decades. In Westport, a traditionally Democratic area, only 65 affordable units had been approved for construction in 30 years, the report noted.

In Long Island, the mass production of cheap, single-family homes on Long Island accelerated white flight, which had lasting effects. A 2002 study from ERASE Racism ranked Nassau County as the most segregated in the nation. Census data from 2010 showed the county ranked the highest in segregation compared with counties of similar size.

“Having done civil rights work nationwide, and in the Deep South, the level of negative reaction you get [on Long Island] to an affordable housing proposal is very visceral, comparable to or more intense than anything I’ve seen anywhere in the country,” said Thomas Silverstein, an attorney who specializes in fair housing at the D.C.-based Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. “People moved out to the suburbs, defining their lives and existence in opposition to what they perceive to be wrong with the city, which is racially coded in a lot of ways.”

The Obama administration’s AFFH rule required local governments to track patterns of poverty and segregation with a checklist of 92 questions to gain access to federal housing funds. Intended to boost enforcement of the Fair Housing Act, its implementation was just getting started when the Trump administration reversed it.

“What are we trying to accomplish with Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing?” Carson posited in his sit-down with TRD. “[Critics] are trying to stop segregation and, in order to do so, create these massive surveys. They come up with all kinds of statistics but nothing changes. We are saying, Why is there segregation?”

Asked about the scale of the problem, Carson said, “I don’t know if I would say [housing segregation] is widespread. Does it exist? Of course.”

Silverstein sees things differently. “The 2015 rule created a process for addressing opposition to affordable housing development that would disproportionately serve people of color and people with disabilities and other protected classes in white suburbs,” he said. “The new proposed rule does away with that process.”

One Park Place in Peekskill, New York

Instead, municipalities can choose to implement any three measures of 16 that HUD has defined as barriers to desegregating housing, Silverstein said.

“Some are low-hanging fruit, and others are not relevant at all,” he added.

But he cautioned that the Obama rule was not a panacea. “It would be naive to suggest that, since 2015, wealthier white suburbs have dramatically started changing their behavior,” he said. “If you have a HUD requirement, HUD still has to enforce it, exercise real oversight, and this 2015 rule was really only being very seriously implemented for a very short period of time. Some jurisdictions hadn’t even implemented it.”

Still, such measures can be the difference between action and inaction, according to Gates. “For municipalities that don’t value affordable housing, you need more of a stick, quite honestly,” he said. “In New Jersey, there’s a real judicial stick to create affordable housing in municipalities that don’t value it.”

One of the most racially diverse states in the country, New Jersey still remains highly segregated. While 44 percent of the state’s residents are non-white, 22 percent of the municipalities there are more than 90 percent white, according to the American Community Survey.

A 2017 ruling by the state’s Supreme Court — the “judicial stick” Moses was referring to — determined that towns would be held accountable for a 16-year “gap period” where fair-housing laws were not being properly adhered to. The court mandated that towns across the state zone for 100,000 additional units of affordable housing over the next decade.

“We have fair housing settlements in place with more than 300 towns in New Jersey right now,” said Anthony Campisi, a spokesman for the Fair Share Housing Center, a public-interest organization based in New Jersey. He said the litigation, which kicked off in 2015, had “opened the floodgates” for getting towns on board with aggressive fair-housing measures.

As a result, he said, “we think we have the strongest fair-housing framework of any state in history.”

Approval migraines

Scott Rechler’s RXR Realty and a previous developer spent a decade to gain approval for twin condo and rental developments in Long Island’s Garvies Point. Closings at the luxury Beacon condo are expected to begin this year, while the Harbor Landing rental building has just opened its doors.

Along the way, the developer battled staunch community opposition, including five Article 78 lawsuits, said Joseph Graziose, an RXR vice president.

The Garvies Point projects have affordable units — a minimum of 10 percent is mandated by the Long Island Workforce Housing Act, a state law passed in 2008 — and Graziose said the community welcomed it. But if the challenges of building a more affordable project would render it unprofitable, it likely will not happen.

“We want to do good in communities, and if an affordable housing component is what’s needed, we’re going to figure out a way to do it,” he said. “But at the end of the day, one plus one has got to equal two, right? Developers, investors, people aren’t going to go into something that is a loss.”

Jon Vogel, senior vice president of the publicly traded real estate investment trust AvalonBay Communities, said the need to address housing supply — in Long Island, in particular — is urgent.

“Long Island has nothing,” he said. “There is no one in Long Island saying, ‘Hey, we need more affordable housing,’ other than a couple of smart planners.”

Housing stock, in general, is in short supply, he added, a point that’s particularly pressing as younger people try to enter the market.

What’s the sticking point holding up more development? “I think the answers range from misunderstanding of what is being offered in terms of high-quality rental housing … to more nefarious instincts related to race and other concerns,” Vogel said. “It’s an unfortunate situation, but I think it’s mostly a combination of misunderstanding and misplaced fear.”

Near the Long Island Rail Road’s Huntington Station, a high-density rental development from AvalonBay was stalled for years because of opposition from residents. It finally opened in 2014.

David Pennetta, the director of Cushman & Wakefield’s Long Island office, said community members had initially complained about people coming from “Brooklyn and the Bronx” to fill the project’s 379 units. But in the past five years, he said, two thirds of the residents in those apartments come from within a half a mile of the building.

The project’s rental units go for as much as $3,435, according to the developer. Nearby, a residential complex that was purchased by private equity firm Eagle Rock Advisors in 2008 and renovated is advertising a two-bedroom unit for about $2,500 per month, according to the company’s website.

Some developers are trying novel approaches to get approval for residential projects in the suburbs. “A development in Smithtown, Suffolk County, is doing all the infrastructure work, which helps to convince the village to get on board,” a person familiar with the development said. “[The developer] is working to gentrify the neighborhood, bring more housing to the neighborhood, but not every village or township wants that.”

In Peekskill, on Metro-North’s Hudson Line, Alma Realty decided to build a 183-unit luxury development, which it expected would be more welcomed by local government than low-income housing.

“A lot of these towns want to attract higher-earning residents to increase their tax rate. They want to bring in more well-heeled people with more disposable income,” Zayas said. “There was zero interest in affordable housing.”

Even so, the firm — which primarily owns rent-regulated multifamily buildings in New York City but has recently been doing more ground-up development — also spent years gaining approval, during which time “two or three mayors” cycled through, according to Zayas, who said the project ended up being the largest in Peekskill’s history.

Seth Pinsky, a former RXR executive, said more attention should be paid to where elected officials are creating affordable units, and for whom.

“In a world of limited resources, governments can create many more units for middle-income households with a fixed amount of money than they can for lower-income households,” he said. “It should not be surprising, therefore, that this is often the part of the market that elected officials target.”

Moving the needle

Since the Newsday investigation came out in November, sparking condemnation of race-based steering from the public and the wider industry, brokers have been on high alert, particularly on Long Island.

The National Association of Realtors has also overhauled its approach with plans to review state licensing laws, conduct anti-bias training and offer a fair-housing testing program.

But developers say potential changes from New York’s State Legislature, going forward, could make constructing affordable projects more difficult.

AvalonBay’s Vogel said the cost of building housing outside of New York City would be greatly increased if legislation mandating prevailing wage for workers on some developments — a bill that was left off last year’s raft of progressive reforms — were to pass.

The plan, which was included in Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s January state budget proposal, would require developers to pay a “prevailing wage” on projects where government subsidies cover 30 percent of the total cost if it exceeds $5 million.

But such legislation would, in effect, force developers to pay union wages in many cases.

As such, Vogel said he is keeping a close watch as the bill gains traction in Albany. The potential increase in construction costs for developing housing could be 25 to 50 percent, he said.

“At that point the value proposition isn’t there to invest in housing,” Vogel said. “Not all our projects have [tax abatements], but many in Westchester and Long Island do.”

Unlike the rent-reform measures passed last year, which only affected existing housing stock, a prevailing-wage bill could change the financial calculus for future affordable housing projects in the suburbs.

Like last year’s version of the bill, some existing projects that receive tax exemptions would be exempt, and multifamily developments where 30 percent of units are affordable would also be spared.

On the heels of HUD’s fair housing rollback and continuing local opposition to large development, a prevailing-wage bill that does not exempt affordable housing could hinder developers’ projects — and also stymie efforts to diversify New York’s suburbs.

“Setting the threshold at 30 percent will probably allow most of these projects to move forward without setting prevailing wage,” said one developer who asked to not be named, citing the sensitivity of the negotiations. “If not, it would grind them to a halt.”