Editor’s Note: This story originally published on April 10, 2020. On April 16, news broke of Housing Justice For All and the Philadelphia Tenant Union’s planned rent strikes for May 1.

The Philadelphia Tenants Union recognizes that not all tenants have the stomach for an all-out rent strike just yet. So in a new manifesto, it suggests “baby step” collective action to help them get there.

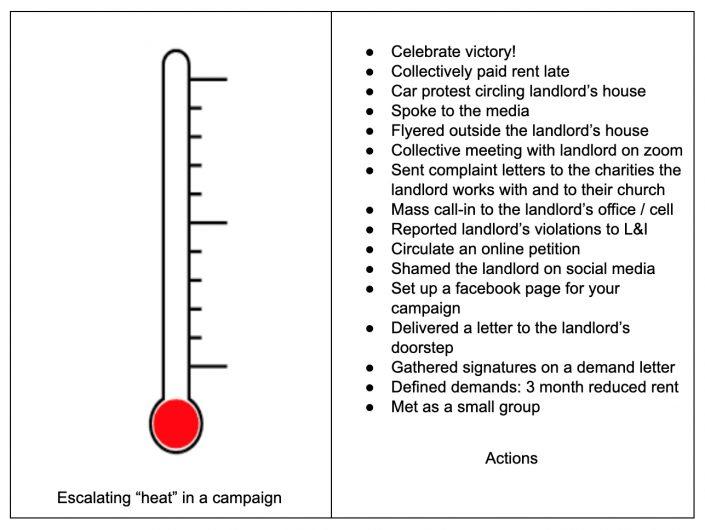

“Escalating actions help,” the union wrote in the manual released last week, at a time when landlords are grappling with nonpayment of rent. “Many tenants who are hesitant about an action that is ‘too radical’ may be radicalized when the group decides to settle on a less scary step first, and find it doesn’t meet their needs.” The union suggests incremental efforts such as “simultaneously paying rent late on the same day” and “car protest circling landlord’s house” and offers a thermometer graphic to help tenants keep progress on the way to a rent strike. The maximal point? “Celebrate victory!”

(Credit: Philadelphia Tenants Union’s COVID-19 Organizing Guide)

Across the country, tenants are ditching door-to-door outreach in deference to social distancing and instead taking their organizing virtual. They’re hatching plans over Zoom, creating digital guides for rent strikes and drumming up support on messaging apps. But the rent strikes now underway — there are at least 71 across the country, while a New York petition to cancel rent has garnered nearly 90,000 signatures — bear little resemblance to conventional ones, which are mostly used to pressure individual landlords into making necessary repairs. Although landlords will certainly take a hit if tenants skip rent en masse, the intended target of this new wave of strikes is the government itself. Tenants hope that sustained and organized pressure will lead lawmakers to cancel rent and forgive mortgage payments.

To have a fighting chance with the state, tenants will need to be organized on a mass scale that is not there currently.

“The state will intervene, as it already has, but it will most likely intervene in favor of bailing out landlords and the housing market rather than tenants,” the Philadelphia union’s manual states. “To have a fighting chance with the state, tenants will need to be organized on a mass scale that is not there currently.”

Systemic shock

As the pandemic cripples the economy and puts millions out of work — 17 million people applied for unemployment benefits in the past three weeks alone, according to the Department of Labor — multifamily landlords are bracing for the consequences.

In the first five days of April, nearly a third of tenants did not pay rent, according to the National Multifamily Housing Council, although some are expected to pay in the coming days. A mass rent strike, however, would put serious strain on the system.

Barry Rudofsky

“We are counting on payments from tenants who are still employed or not facing serious hardships, so that we can work with those hardest hit,” said a spokesperson for Barry Rudofsky’s Bronstein Properties, which owns around 5,000 mostly rent-stabilized units in New York City. “Current rental collections are already significantly down” in the Bronstein portfolio, the representative added, and the federal government must prevent the “impending tidal wave” should landlords be unable to pay mortgages, property taxes, utilities and essential workers.

“There will be a domino effect,” the spokesperson said. “And only the federal government can put in place the policies and protections needed.”

Historically, rent strikes have almost always been a last-resort response to what tenants saw as extreme landlord neglect.

We think landlords are going to need help too — someone should be organizing landlords.

New York tenant groups put out a toolkit last week which noted the first rent strike in New York City in 1907, carried out by immigrant Jewish women, and rent strikes in Harlem and Brooklyn later that year, organized by the Socialist Party. Before a law was passed in 1929 allowing tenants to withhold rent for lack of basic services, 1,000 tenants in 25 buildings in the Bronx went on a rent strike in 1917 in the “No Heat/No Rent Campaign.”

The rent strikes being organized now, however, are not about living conditions.

Tenants are “coming together out of desperation,” said Amy Schur, campaign director of the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment. Her group is threatening a general strike on May 1 if California Gov. Gavin Newsom does not forgive rent as well as mortgage payments.

“People are pledging their intention to withhold rent, so the demand is of government,” Schur said. “We think landlords are going to need help too — someone should be organizing landlords.”

Cea Weaver

Cea Weaver, a key organizer with New York-based Housing Justice for All, said the push for collective organizing stems from a growing realization that tenants have “nothing to lose” by acting together.

“What we are trying to do,” Weaver added, “is turn this moment into something powerful, using a moment that is scary and lonely and turning it into a way for them to demand a different outcome.”

Neural networks

Nathan Pensler, then a resident of an eight-unit building in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, recalled a five-month strike at his building in 2017 over what he said was a lack of heat, construction harassment and unsafe conditions. After construction workers mistakenly nailed two-by-fours over two tenants’ doors, trapping them in, the tenants weighed collective action. Before the tenants decided to withhold rent, the building had lacked a boiler for two straight winters.

“In ordinary circumstances, people aren’t going to say ‘a rent strike sounds fun!’ — and only some of the tenants were facing really egregious conditions,” Pensler said. “It took a while for newer tenants to feel they had to organize as a group, to build up trust, to get everyone working as a team.”

But the situation now is totally different.

“The lessons of my building don’t provide any kind of road map for what we’re seeing right now,” Pensler said. “There are hundreds of thousands of people who simply won’t be paying rent because they don’t have the ability to pay.”

Such is the situation at seven Brooklyn buildings owned by Alma Realty, where more than 150 tenants calling themselves the Taaffe Tenants Association notified their landlord in a letter that they intend to withhold rent, “whether by inability or solidarity,” for 90 days starting May 1.

“While we intend to withhold rent payments regardless of your response, we want to make it explicitly clear that what we are asking for is your solidarity, support and communication,” the letter reads. Astoria-based Alma, headed by Efstathios Valiotis, did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Citywide, tenant groups are looking to organize not just at the building level, but at the ownership level — to extend their actions beyond their own hallways and across portfolios owned by the same entity.

“‘Neighbor from another hood’ is the nomenclature for a co-portfolio neighbor,” said one person on a rent strike how-to call on the videoconferencing platform Zoom.

But just because groups are educating tenants on how a rent strike works doesn’t mean one is imminent.

“We have made no specific plans for a rent strike,” said Karen Harvey, campaign director of the Philadelphia Tenant Union. “As a person of color who has been negatively impacted by eviction, we want to make sure that any solutions to our current housing crisis will ensure the safety of all tenants in Philadelphia and help to build renter power.”

Calling Uncle Sam

Landlords and tenants agree that financial relief should come from the federal or state government. But they are at odds over the form that relief should take.

Most landlords would prefer a tax abatement, or direct assistance to renters via a means-tested rental subsidy to keep the rent checks flowing. Tenant advocates and their allies want rent and mortgage bills canceled.

“We are currently excluded from federal programs, but know that direct rental-assistance vouchers must be provided by the federal government to keep families in their homes and allow for the continued payment of building mortgages, property taxes, sewer, water, building staff payroll, and the hundreds of small businesses employed as vendors,” said the spokesperson for Bronstein Properties.

Federal assistance may be more likely than tax cuts from city governments, whose coffers are running bare as they grapple with an unprecedented crisis. In 2020, New York City projected revenues from property taxes to be nearly $30 billion, or about a third of overall revenue.

Eli Weiss

Waiving landlords’ real estate taxes would likely “crush the city’s budget,” said Michael Feldman, whose property management firm Choice New York oversees 7,100 units across 210 buildings.

“Tenants paying rent and lenders — it’s a delicate ecosystem,” Eli Weiss of Joy Construction, a developer and landlord active across New York, said during a virtual seminar about rental cash flow during the coronavirus crisis. “If there’s not a federal stimulus, I don’t know that New York City will be able to function for an indefinite period of time without receiving real estate taxes in June.”

Primal fear

The severity and universality of the coronavirus pandemic has put housing’s core contradiction into the spotlight: that it is an essential service, but a business, too.

Jason Frosch, a partner and lead trial attorney in the Loft Law practice group at Kucker, Marino, Winiarsky & Bittens, said many of his clients have heard from their tenants about potential rent strikes.

We have to bite our lip, because some tenants were demanding, and said ‘I’m not doing this,’ and ‘I’m not doing that’

“Some of [the tenants’ communications] are nice, expressing legitimate concern about what’s going on, while some of them were a bit more demanding in tone,” said Frosch. “Landlords have a lot of obligations right now, and just so happen to provide a service that is one of the essential survival requirements of life — which is shelter.”

Robert Nelson

Robert Nelson, whose Forest Hills, Queens-based firm Nelson Management owns 7,500 units throughout New York City, said he has not seen a significant drop-off in April rent collection. Many of his renters receive a federal subsidy, which was expanded by the federal stimulus, and others are professionals who are not as hard hit as service workers, for example.

Even so, some tenants have called Nelson, demanding rent relief.

“We have to bite our lip, because some tenants were demanding, and said ‘I’m not doing this,’ and ‘I’m not doing that,’” Nelson said. He noted that the $2 trillion federal stimulus package already contains a significant amount of money for tenants to “continue to pay for their lifestyle.”

“I’m not talking about taking a trip to the Bahamas,” he said. “But I’m talking about a roof over your head, and food on your plate.”

As the New York strike toolkit notes, landlords may hesitate to respond with “waves of eviction cases,” because of the reputational risk. Few landlords want the headlines that would come with attempting to boot tenants during a global health crisis.

Even so, individual landlords may hesitate to cancel rent for striking tenants who are already not paying rent, because doing so might endanger their right to process evictions once the crisis concludes. Either way, the landlord doesn’t get paid, and renters are aware that creates a fraught situation for them, too.

“We need to think about contingencies, what’s our fallback, what’s our Plan B?” said Dylan Saba, an eviction defense attorney. A general strike’s success, he said, depends on whether enough people can be persuaded to take action.

“Let’s say we fall short of that [threshold],” Saba said. “What if we’ve convinced 40,000 people, who otherwise would be able to pay full amount or negotiate a lower rent, to withhold their rent, and we don’t achieve our demands? We’re looking at putting 40,000 more people at risk of eviction.”