Mark Macias took space at a WeWork office on Fifth Avenue “before anyone knew what WeWork was” — growing his eponymous public-relations firm from two employees to four, then six.

But with the co-working giant keeping its U.S. locations open during the pandemic, Macias wants out.

He’s one of many customers angry that WeWork is charging fees even though most of them can’t go to work under Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s late-March order. He thinks the company decided to stay open for financial reasons.

WeWork has disputed this, saying its spaces are open to accommodate essential businesses, and because WeWork runs a mail service. It declined to say how many businesses exempt from Cuomo’s ban are using the locations.

As companies across the world wrestle with the financial and public-relations challenges of the pandemic, co-working firms have an especially difficult dilemma: balancing tumbling revenues against the individual needs of members, whose support is crucial to their survival.

One member of co-working company Bond Collective said the firm refused to cancel her contract, which had a few months left, despite her protests that she couldn’t legally use Bond’s space or services because of the governor’s order. Bond offered her a pause on the membership, which she declined, viewing it as an extension.

In emails viewed by The Real Deal, a representative for Bond told her the company’s monthly revenues had fallen between 50 percent and 75 percent because of discounts and cancellations. Still, she rejected the idea that Bond and its customers were all in the same boat.

“They already have the funds to survive, whereas the businesses they’re housing are basically crumbling because they’re being forced to pay for things that they’re not receiving,” said the customer, speaking on condition of anonymity.

Bond Collective’s Shlomo Silber

Bond’s CEO, Shlomo Silber, said the characterization was false.

“We are a small business. We’re not like a big, venture-backed company,” he said. “We’re just trying to figure out a way that everybody can stay alive.”

It’s really hard to keep everyone happy in a global pandemic

He said Bond is offering to pause memberships for customers who cannot use their space and a 25 percent discount to those who do need to use it.

“We’d be out of business if we just said, ‘Hey, no problem, all contracts can be broken and everybody can just pick up their stuff,’” Silber said. “That essentially kills our business.”

“It’s really hard to keep everyone happy in a global pandemic,” the CEO added.

The member said when her business resumes, it won’t be in a co-working space.

“Our team will find another solution,” she said.

What co-working will look like in a post-pandemic world is uncertain. Not only does the model rely on people gathering in dense environments, but the core product is essentially the members themselves and the community they create — adding pressure to the decisions companies make in hard times.

Other Silicon Valley companies are also struggling to find a balance. Airbnb, a multibillion-dollar startup, relies on homeowner “hosts” to populate its global network of listings. But its offer to refund guests’ deposits during the pandemic triggered backlash from many Airbnb hosts, whose income disappeared. The company later issued an apology and set up a relief fund, but many hosts have reportedly turned to other sites and longer leases.

I’m not putting my health at risk and moving anything until the governor lifts this nonessential worker ban

Co-working firms have taken different approaches to the pandemic, but none has been spared its ravages. The Wing and Soho House have closed all locations and laid off most of their staff. Flexible-office providers Knotel, Industrious and Convene, which differ from co-working companies because they mainly offer private office space, have also slashed head count.

Read more

Macias, who has been using a WeWork office for nine years, said he asked the company for relief from his April rent and was offered half off for April and May, but only if he signed a yearlong lease. When Macias refused and said he wanted to wrap up his month-to-month arrangement, the company said he would have to move out by April 30.

“I’m not putting my health at risk and moving anything until the governor lifts this nonessential worker ban,” Macias fired back in an email April 10.

He questions how WeWork is allowed to keep his site open, and insists there are no essential businesses on his floor. His neighbors include a perfume maker and a nonprofit. WeWork declined to comment on Macias’ case and his assertions.

We’re working out deals with our customers, we’re working out deals with our landlords, they’re working out deals with their lenders. We’re all trying to weather the storm

The Empire State Development agency, which determines which businesses can keep workplaces open, did not respond to questions about how it treats co-working, which is not on its list of essential industries. However, a representative of Mayor Bill de Blasio, whose Office of Special Enforcement has been patrolling the city to make sure companies are abiding by the rules, said nonessential businesses that support essential ones are exempt from the ban.

The enforcement unit has inspected 11 WeWork locations and found them in compliance or obtained compliance with verbal instructions, the representative said.

The question about whether members may be charged rent for services they can’t use is a vexed issue. In April, New York Attorney General Letitia James called on the parent company of New York Sports Club to stop charging member fees after the governor ordered all gyms to close. “New Yorkers have enough to worry about and should not be forced to pay for services NYSC is no longer providing,” she said, vowing to take legal steps if necessary.

But several executives in the flexible-office industry said such framing is not realistic in a business-to-business context, given the complexity of financial obligations involved.

Industrious CEO Jamie Hodari

“We’re a B-to-B company in a giant web of B-to-B payments, and we’re working with our landlord partners and our vendors and our utility providers,” said Industrious CEO Jamie Hodari.

“We’re the first on the payment side to say, ‘Can we work something out? What can we do?’ … I don’t think any of them have turned up and said, ‘Hey, never mind, we’re shutting up business; you don’t have to pay anything.’”

Industrious enters into managing agreements rather than leases with its landlords, Hodari said. He believes questions about whether locations should stay open are misplaced.

“What we do is indistinguishable from what an office building does,” he said. “You can’t really change the locks and keep people from accessing their property.”

Breather CEO Bryan Murphy

The company is supporting members who are working from home during the pandemic, and is addressing their individual situations on a case-by-case basis, he said. That sentiment was echoed by Bryan Murphy, the CEO of flexible-office company Breather.

“We’re working out deals with our customers, we’re working out deals with our landlords, they’re working out deals with their lenders,” he said. “We’re all trying to weather the storm.”

Murphy believes the flexible-office model is in a stronger position than co-working because the former involves leasing standalone private offices and offers customers short-term leases, which he predicts will become more desirable as people think about returning to work.

“Companies that are currently in co-working facilities have little desire to go back to co-working facilities for two reasons,” he said. “One is because of density, and, two, the lack of control of who’s in the space.”

But Bond’s Silber believes any move away from co-working will be temporary.

“We’re yet to see what the long-term changes will be, but on a personal note, I think people want to be in an engaging environment and want to work together,” he said.

“In the short-term we’re going to do whatever we can to make the space safe, whether that’s new methods of cleaning, new methods of social distancing in common spaces. In the long term — I have a lot of hope for this.”

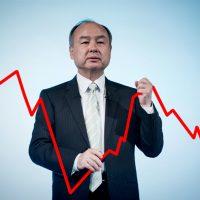

WeWork CEO Sandeep Mathrani

In an email to brokers last week, WeWork CEO Sandeep Mathrani said the company planned to evaluate its floor plans, introduce sanitization stations and post signage in meeting rooms about social distancing.

Sam Chandan, dean of NYU’s Schack Institute of Real Estate, said in a TRD webinar that if the trend away from density persists it would threaten co-working’s business model.

NYU’s Schack Institute of Real Estate Sam Chandan

“Many co-working spaces are going to be in a position to very quickly adapt to people’s desire to have wider hallways, more open spaces, lower levels of density,” he said, “but ultimately that does affect the profitability and viability of some of the co-working spaces that are in the market today.”

Write to Sylvia Varnham O’Regan at so@therealdeal.com